Eh? See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muzungu

I’m recently back from spending a few weeks in Africa. While there we visited some impressive non-profit organisations and got up close to some amazing wildlife. Below are four short summaries which hopefully give a flavour of the trip.

1. Don’t mention the war

When I would tell people I was visiting Africa, and list off the countries we planned to go to, it was always Rwanda which triggered the raised eyebrows. Unfortunately the country is now forever associated with the word ‘genocide’, which makes it a tough sell from a tourism perspective.

So, arriving there I didn’t really know what to expect, and I was right!

The capital, Kigali, is a busy city. Taxi-motos buzz in all directions, with both drivers and passengers wearing distinctive green crash helmets. All around is evidence of investment - roads being repaired and buildings going up. Mobile phone towers mark the skyline. Unlike many other third-world cities, you are immediately struck by the cleanliness of the place. Plastic bags have been banned by the government, and there are regular civic days when everybody is expected to clean up public areas. People are friendly and care about their appearance.

Nobody seems inclined to spend too much time dwelling on their horrible recent past, to be honest - they are all far too busy trying to improve their future.

We visited some genocide sites, including a church on the outskirts of the city, where 10,000 people were massacred. The victims’ blood-soaked clothes are kept as a memorial. Down in the crypts are the remains, including some skulls with visible signs of a common killing method - a machete to the side of the head. These places have a similarly eerie feeling to Holocaust memorial sites, although here all of this violence occurred only 15 years ago, and the fighting continues today over the border in the Congo. It’s chilling to think that everybody over the age of 25 was likely involved in all of this somehow, and not many of them came out of it looking good. Given that, it’s a miracle that the country functions at all.

Out of town the paved roads give way to rich brown dirt tracks, and the steep hillsides quickly become covered in thousands of tiny small-plot farms. Most of these belong to subsistence farmers (i.e. people who eat everything they grow, and would eat more if they could grow more).

We visited an organisation in Nyamasheke in the south of the country called One Acre Fund (or “Tubura” locally). They work with farmers to help them improve their yields by providing credit for better seeds and fertilizer as well as training (teaching people to plant in rows etc). They work from the bottom up, starting with the obstacles for individual farmers who are typically working with really tiny areas of land. In the place we visited they have about 15% of farmers using their services. Given that these people have on average increased their income by over 70% since joining the program, why isn’t this ratio higher? We asked one of their customers who explained that partly it is because others had heard that in rich countries people didn’t like using fertilizer anymore because it was bad for their health. Where do you start with that? I was tempted to try and explain that many people in the first world pay good money to try and stay as slim and as fit as she is, but couldn’t find the right words.

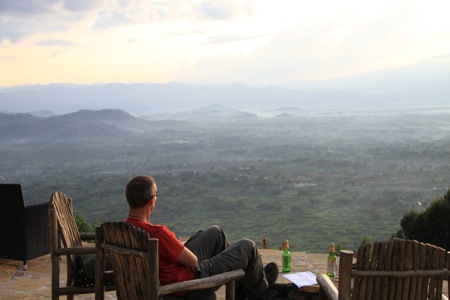

Traveling north we flew over stunning lakes which would not have looked out of place in Marlborough or Fiordland. We arrived in Ruhengeri at dusk, and as we watched the sunset over the nearby volcanoes the valley below filled with smoke from the wood fires cooking dinner. The next morning we got up early and trekked into the national park to see the mountain gorillas. We visited a family called Group 13. They are Agashya, a 200kg silverback, 9 females and 12 children. After walking for about an hour through the bamboo forest we suddenly come across them. They are stunning creatures and it’s a privilege to be able to be so close to them. The guides warn you to not point and to adopt a submissive stance, but they don’t have to tell you to shut up - that comes naturally as soon as you see them, the only sound to be heard is the click of camera shutters. We sat with them for about 20 minutes before torrential rain set in. At that point they all curled up and looked at us getting increasingly soaked as if to say “seriously, you’re still here?”. Even as the risk of hypothermia increased, this was not an experience we wanted to miss.

Rwanda is a beautiful country. If you have the chance to visit I throughly recommend it.

Just leave your raised eyebrows behind!

2. Things can only get better

Mapendo is an organisation that works with the most desperate of refugees. After showing us around their office in Nairobi, Kenya, and explaining a little about what they do, they took us to visit a Congolese family living in the city, who they are currently supporting with rent and food, and helping with their application to relocate to the US.

The family is a mother, about my age, and her six kids (her husband was taken by rebels during the fighting and is missing, presumed dead), plus her 16 year old step-daughter who has two newborn kids of her own (a consequence of being raped by her former employer in Kenya). They all escaped from a refugee camp where they were treated pretty poorly, by all accounts - about as poorly as you can imagine, in fact. They all live in a single room in a large apartment block, about 2m x 5m. They fold out bedding at night, and during the day it doubles as a mat to sit on. There is no furniture. Pots and pans for cooking are piled up on a shelf on one wall and by a shared sink outside. When we arrived they turned on the single incandescent light bulb that lights the room, previously left off to save on power.

We spoke a bit with the kids. The younger ones are in school and speak some English (much better than I do Swahili, anyway). We asked why they were not at school that day: “Because you came to visit” they explained, to our embarrassment. The most chatty was about 8 years old. “What are you going to do when you leave school?” we asked. “Play football for Liverpool” was his immediate answer. We tried to explain that was a long shot, and it might pay to have a backup plan, but he was adamant: “I’m very good” he beamed back. The oldest, who is 18 years old and is effectively the father in the family now, was carrying a beaten up dictionary. He is too old for school, but is obviously keen to learn still. I showed them some photos of my kids on an iPhone which they seemed to find quite amusing. Like kids everywhere they didn’t worry about how to use it, they just started playing with it and quickly worked it out.

It costs about US$500 per person to help these sort of people jump to the front of the UNHCR resettlement program queue, and eventually escape their circumstances. Once you’ve stood in their “house” you’re hard pressed to argue that is not money well spent. It’s not difficult to imagine, if they do manage to get to the US, that they could land on their feet - who knows what they will be within one or two generations.

Future football star, or something

3. Investing in slums

It takes a certain kind of person to look at thousands of the poorest people living in slums, like Kibera in Nairobi, or at rural farmers struggling to feed their family let alone anything more than that, and see an opportunity to invest rather than merely gift.

During the trip we were lucky to meet a few people like this, who understand that what poor people really need most is not sympathy but income, who understand how important incentives are, who measure impacts rather than outputs, and who understand that to make any sort of dent they need to create an organisation which exists beyond their own contribution.

I was introduced to Martin Fisher from Kickstart when he visited New Zealand last year. He said enough in that brief meeting to convince me, and it was great to be able to visit him in Kenya and see the work he’s doing first hand (I also understand a little about incentives, and am comfortable admitting that there is a selfish motive for me in donating to organisations working in interesting places I can visit - see Holy Cow! my post about my previous trip to Nepal, for example).

Kickstart run a business which sells irrigation pumps to farmers. They took us to visit some of their customers. Typically these are people who previously irrigated by carrying water to their crops in a bucket. With the pumps they can significantly increase their yields, giving them income to reinvest one way or another. A popular option it seems is building a better house for themselves, and we were invited to visit a few of these houses when we visited the farms - they are usually obvious in that they are constructed of bricks and have metal roofs, as opposed to the mud and thatch alternatives which are more common. Kickstart have also successfully created an eco-system around these products, which creates opportunities for other small business, like farm supply stores who sell the pumps for a small margin, and repair men who provide routine maintenance. Currently for every $1 that is donated to support the organisation they are able to deliver about $15 of additional farmer income, meaning it costs about $300 to permanently lift a family out of poverty.

In Nairobi we spent a morning with Jay Kimmelman from Bridge International. In his previous life he was founder and CEO of Edusoft in the US. Visiting the slums in the city he made a simple observation - the reason poor kids aren’t learning is because nobody is teaching them. So, he set up a business which builds and runs private schools in the poorest areas. Parents pay about US$4 a month in school fees, and as a result pay close attention to the education which is delivered. The way these schools are set up is amazing - everything has been thought through and planned and is part of an overall system to ensure that the right service is delivered as efficiently as possible - a so-called “school in a box” covering everything from curriculums to recruitment of teachers and managers through real estate (finding and purchasing sites for schools at reasonable prices) and construction. Jay is not messing about - he is creating systems which will allow him to build hundreds, then thousands of schools. He started with one school, proving that he could deliver the service at the required cost point, and that people would be prepared to pay. He puts a huge amount of effort into testing and measuring results, so he can guarantee that the educational outcomes are good. Actually, they are spectacular, even compared to schools in the first world. I was interested to hear him explain the top three teaching goals which form the basis of their curriculum: 1) Reading with Understanding, 2) Maths, 3) Critical Thinking (the third one especially is missing in action in many first world schools). Now he is scaling up quickly - recently opening five schools at once to prove that could be done, and now many more, forcing the organisation to continue to refine and automate processes and systems so that nothing breaks. And this is a proper business - rather than asking for donations to fund the early stages of the business he sold shares and retains a good percentage for himself - he expecting all of this to make a profit too!

Those are just two examples. There are more like this, such as Living Goods who we visited in Uganda, and Komaza and Nuru International who are working in rural Kenya.

I was impressed by the way these organisations are using technology. About 80% of the parents whose kids attend Jay’s schools pay via mobile phone (everybody, it seems, has a pre-pay phone and payment systems like M-PESA seem to work well). They have created an entire command line operating system for their school managers to use running on top of SMS, for everything from authorising payroll to reporting test scores. They use handheld GPS devices to mark out potential school sites, and the data is automatically uploaded into Google Maps where they can check size and location and check for existing titles etc (not a simple matter in the slums). We even met a group who use face recognition in Picasa to authenticate customers who want to withdraw money from the community bank they run as part of their program - it will seem a bit old school typing in a PIN number next time I use an ATM in New Zealand!

These organisations are also all very focussed on measuring their impact. They are not so fussed about the number of pumps sold or the number of schools built - they are much more interested in the amount of money that farmers earn by using the pumps and how many kids are educated to an acceptable level. While it can feel a little clinical to talk about people as numbers the alternative is to focus just on outputs or, worse, completely ignore the impact and just think about the warm fuzzies you get when you donate.

See: Real Good Not Feel Good for more information on this

Muzungu on foot pump:

: and on hose (this is Martin, the inventor of the pump we’re using)

This grandma earns more than both her sons combined, and proudly showed us the new house she and her husband have built with their profits. She was very nervous when I was taking these photos, as she didn’t want me to show the table empty - it would be considered rude to invite guests in without offering them food.

The most impressive Avon lady in Uganda

Home Sweet Home

4. Wildlife worth protecting

How do you stop poachers from killing off the amazing rare wildlife in a place like the Luangwa Valley in Zambia?

To finish the trip we visited an organisation called Comaco, run by an impressive American called Dale Lewis, who has been living in Zambia for many years and who has come up with an interesting answer.

He works with local farmers to add value to the commodity crops they grow. Bouncing along in the back of a truck, down a long dirt road full of pot holes that you could easily lose a small car in, he took us to visit the factory. Women are employed to sift the grains. They can choose to be paid a fixed rate or a per-kilo rate (they all choose the later). Inside there is a simple manufacturing setup for peanut butter and honey and mielie meal. Everybody wears white coats and gloves. Staff carefully weigh packed products, then use a heat gun to add a security seal to the package. The finished items are sold in the capital, Lusaka, and also in local stores.

The profits from all of this are feed back to the farmers and local community in the form of bonus payments, to provide incentives to locals to stop poaching. They now have over 25,000 farmers working with them, and in the process have confiscated thousands of guns and snares previously used to hunt bush meat to trade for food and money.

And, the wildlife that is protected is spectacular. We went into the National Park at dawn and dusk and were able to see giraffe, hippo, and hundreds of elephants, as well as more zebra than we could count. After dusk we found a small pride of lions, and tracked them with the spotlight - we were assured that this doesn’t bother them as much as you’d think, which is important because the only thing between them and us was a camera!

Having all of these animals walking around right around the car, close enough to touch, is truly breathtaking.

No clowning around in this factory!

Okay, those are teeth…time to leave them alone!

Yes, Wonderful

Thanks to Kevin, Laura and Mahri from Mulago Foundation and Sam and Nina from Jasmine Social Investments who kindly let me tag along on their trip.