I have a complicated relationship with honesty, much of it instilled at an early age. As an innocent six-year-old I didn’t realise it at the time but underneath the red suit and white beard, the Father Christmas we’d visit at James Smith department store every year was an old family friend and he had me completely fooled. He seemed to know everything about me and would even recall specific details of presents that he’d given me and my brother and sisters in previous years. I was convinced he was real.

The adults involved all thought that was pretty funny. I was embarrassingly old, maybe 10 or 11, before I finally accepted the truth. I remember being completely disillusioned. If Father Christmas wasn’t real, what other crap had I been fed? How many other imaginary friends did adults have? More importantly, how did the grown-ups I trusted convince everybody else to lie about it too?

Bribe

If you’re a cynical grown-up, like I’ve become, then at Christmas time there are two options: either pretend to believe, or ruin the spirit of the season for children everywhere.

Why do we do this?

Perhaps it’s all about the bribe. After all, Father Christmas knows if we’ve been naughty and only kids who behave well get presents, right? Well, he obviously makes an exception for hypocritical adults, because they seem to do just fine.

For example, it was many years ago now, but I remember it vividly. We were at a mall and a mum (I assume) was laying into a small kid, who was crying hard. Loudly she said, one word per smack:

How … many … times …

have … I … told … you …

not … to … hit … your … brother?

Kids are so trusting and innocent we sometimes forget. When our youngest son was about three years old, we once accused him of lying to us, and in his defence, he said, “I wasn’t lying. I was sitting up.”

It’s not only by example that we teach kids to lie, in fact, we insist they do it:

Parent: “Alex, say sorry to Kim.”

Alex [sarcastically]: “Sorry.”

Parent: “No Alex, say it like you mean it.”

In other words, “Just pretend you’re sorry, Alex.”

We may as well skip the intermediate steps and just teach them the non-apologies we use as adults like, “I’m sorry if anybody took offence.”

Fake

At the 2010 World Cup, the veteran goalkeeper for the German football team, Manuel Neuer, was involved in a controversial incident in a knockout game against England. Towards the end of the first half an equalising goal by the English was disallowed by the referee despite crossing the line.1 After the game, Neuer said that he thought the way he quickly reacted and played on as if a goal hadn’t been scored had influenced the decision. In other words, he happily boasted about how well he’d cheated.2

The officials involved were slammed by fans and the media for getting it wrong but hardly anybody criticised Neuer for cynically seeking to deceive the referee.3 He may have been the only one who knew for sure in the moment whether a goal had been scored or not, but imagine how unusual it would have been for him to simply admit the truth.

Or, go back even further in the history books to the Los Angeles Olympics in 1984, where Zola Budd and Mary Decker were involved in a famous incident in the 3000m final.

Budd was a polarising competitor even before those games, having switched nationality at the last minute in order to compete at all (South Africa was banned from international competition due to apartheid sanctions). She also stood out from the other finalists by running in bare feet.

Decker was the local hero and one of the favourites to win a medal. So it was shocking when she stumbled about halfway through the race, and fell out of contention, seemingly tripped by Budd.

Immediately afterwards Decker inflamed the controversy by saying that there was “no doubt” that Budd had tripped her intentionally. The officials initially agreed with her and disqualified Budd, who had been booed by the crowd as she completed the race. They later reversed that decision after watching replays.4 Decker herself also eventually changed her story and admitted that she didn’t believe she was tripped deliberately but that her “fall was due to her own inexperience in running in a pack”.5

To add an ironic epilogue to the story, Decker herself was subsequently one of the many 1980s era athletes caught taking performance-enhancing drugs.

Is it cheating if we can get away with it? Sport is full of little ethical dilemmas like this: Is it smart for a batter in cricket to walk if the umpire doesn’t give them out?6 Is it okay for a footballer to pretend to be fouled to milk a penalty?7 Is it acceptable to take performance-enhancing drugs if you can claim they are for a medical condition?8 And do you object if your own team cheats or only when the opposition are cheating? For example, consider the complaints about Richie McCaw’s playing style when representing Canterbury, compared to the satisfied silence when he played for the All Blacks.

Those blurred lines aren’t unique to sport. The temptation to bluff and fake is everywhere. Startup founders are often encouraged to “fake it till you make it”, especially when trying to raise capital.9 Those following this advice are usually easy to spot because they tend to have the same tell: the phoney corporate persona. They talk and dress the way they think a serious business person should talk and dress. When they describe their business or their team they make it sound bigger and more impressive than it actually is yet. But there is always an uncanny valley – you can sense it’s not quite right. Surprisingly, many of them get a long way just by exuding confidence. Those who are good at marketing themselves are always going to hog the headlines. And we tend to mistake confidence for capability, and assume visibility means credibility. So often these people get held up as role models. That crowds out others who are less visible.

Investors often enable this behaviour by expecting certainty. Forecasts are vital for teasing out the assumptions we’re making about the future, and often expose the holes in that logic, but we should always be clear they are estimates not promises. Inexperienced founders often don’t realise that saying “this is how you could help” is a significantly more engaging pitch to potential investors than “I already know all the answers” (which, of course, is never true).

Should we call ourselves a “cyclist” if we don’t ride regularly? Should we call ourselves an “entrepreneur” if we don’t yet have a product for sale and paying customers? Should we call ourselves a “leader” if nobody is following us? We apply aspirational labels like this constantly, but the behaviours that should underpin them are far less common.

Some investors love the bravado of a founder who is full of unearned confidence. Anybody taking that approach, and attracting investors like that, should pause and consider how those same investors might respond if (more likely when) the glitter has worn off. The people who are most attracted to the glamour of an exciting-sounding startup are often the first to go AWOL when things get hard.

Rather than pretending to be something that we’re not, we should try to make the truth good and then tell it. But that’s much harder work.

Pretend

Once, on a flight, one of the cabin crew spotted the icon on my screen and enforced the “turn your phone onto flight mode” rule, waiting to check that I did it. As I sat feeling like a busted criminal, I imagined how it would be if my humble iPhone could magically connect and interfere with the plane’s navigation systems, as they claim in the safety announcement.

If there was even a remote possibility that our devices could “interfere with the plane’s navigation systems” do you think airlines would let us have phones and laptops on board, and (most of the time) just trust us to put them in flight mode? Or would everything electronic be confiscated at security along with nail clippers and 125mL cans of deodorant?

Who is “they” anyway?

Wouldn’t it be so much better for everybody if we were honest about the reasons for this rule. We could simply say: “it’s safer for us all to have stuff like phones put away during take off and landing so that everything is clear in case of emergency”, although that would force us to address the reality that a book or newspaper is just as distracting or dangerous as a device if an evacuation is required.

Then again, this kind of misinformation is a harmless part of the security theatre that is now an ingrained part of travelling.

Just turn off your phone and don’t make a fuss. It’s apparently better for your battery anyway.

Spin

Every company has a story about how it got started: Apple and Google were both started in garages in Silicon Valley, Pierre Omidyar built the first version of eBay to help his wife trade Pez dispensers, YouTube was conceived at a dinner party after founders Steve Chen and Chad Hurley struggled to find anywhere they could upload and share videos they had shot. In New Zealand, Sam was apparently inspired to build the first version of Trade Me after struggling to buy a heater for his chilly Wellington flat.

These stories are more spin than reality. Apple wasn’t really started in a garage;10 nor was Google;11 eBay was created in academic pursuit of a perfect marketplace, not a Pez dispenser;12 the YouTube dinner party may or may not have ever happened;13 and according to Trade Me whether the heater story is true “shall remain a tale of yore”, so who am I to disagree?

There is a good reason for this: journalists ask founders, “Where did you get the idea?” and when they do they’re asking for an evocative origin story. The real stories are usually complicated, nuanced and, if we’re honest, much more boring. So facts get fabricated or embellished and repeated and soon enough the real story is forgotten.

Young companies are really just following the lead of larger corporations, who all employ teams of people to carefully manage their “public relations”. Many of the techniques that are now more or less universal were first employed by the tobacco industry in the 1950s and 60s to “misdirect and reframe” the negative health consequences associated with the products they were selling.14 While we no longer accept that the science on the effects of tobacco addiction is unclear or allow these companies to use things like sports sponsorship to attract new customers, interestingly we don’t question the idea that McDonald’s is a viable healthy choice “as part of a balanced diet” or that taxing the addictive ingredients of Coca-Cola would be “unlikely to influence consumption”.15

If there was even a remote possibility that our phones could “interfere with the plane’s navigation systems” do you think they would let us have phones onboard, and (most of the time) just trust us to put them in flight mode? Or would everything electronic be confiscated at security along with nail clippers and 125mL can of deodorant?

Often the spin is pretty harmless:

We’re sorry for the delay, your call is important to us but all our operators are busy at the moment

Should be understood as

You’re calling at a very predictable peak time, but we’ve decided that the frustration you’ll feel as a result of our decision to under-staff our call centre will not be enough to convince you to change service providers.

Likewise:

The CEO has decided to stand down in order to spend more time with their family

Nearly always means

The CEO was about to be fired but has chosen a more dignified exit.

Nobody ever asks the family what they want.16

The web gets a bit more tangled when the subject matter is more life-and-death. The combination of “died suddenly” and “police are not seeking anybody else in connection with the death” is a code the media use to describe a likely suicide. This is done for legal reasons, in order to limit copycat behaviour (or what officials call “contagion”), but also means that even in situations where it could be beneficial to tell the real story, people are left to either know the code or be a bit confused about what really happened.17

What corporations pioneered, politicians have enthusiastically embraced and perfected. So much so that there are now more communications staff employed by governments than there are journalists reporting on the press releases they produce. The news is full of truthiness – the term coined by US comedian Stephen Colbert to describe something that feels or seems true, even if it really isn’t. As with sporting heroes, we are generally forgiving of this kind of behaviour when it’s done by those we support, and much more scathing when it’s done by those we don’t.

Gravity always wins

Dshonesty is a muscle. It gets easier the more we do it.18 We all fake, bluff and spin when it suits us. We tell our own version of the story. I’m doing that right now! It’s a behaviour that we reinforce in kids from a very young age, but it still makes us angry when others lie to us or beat us by cheating or don’t give us all the facts.

I’m not suggesting that we all become brutally honest. Most of the time when people ask “how are you?” they don’t really care to know the truth so we should probably just say whatever they want to hear. We just need to be more aware when we allow a gap to develop between what seems to be true from the outside (perception) and what’s really true on the inside (reality). That gap always closes eventually. It may happen quickly or it might take years. The bigger the gap and the longer we leave it open the more painful it’s going to be, when gravity reasserts its dominance, for the person who has been faking it and for everybody else who believed them.

So, please, tell your kids the truth about Santa before they get too old.

This is based on a short talk I gave many years ago at Ignite Wellington.

Ironically, the popular George Orwell quote I included about deceipt and telling the truth … doesn’t appear anywhere in his writing.

-

Frank Lampard’s DISALLOWED Goal: Germany v England World Cup South Africa 2010 Last Sixteen, YouTube. ↩︎

-

Germany’s ‘keeper Manuel Neuer: I fooled the referee into disallowing Frank Lampard’s goal for England at World Cup 2010, Goal.com (via Internet Archive), 29th June 2010. ↩︎

-

Frank Lampard’s ‘goal’ against Germany should have stood – linesman, The Guardian, 5th July 2010. ↩︎

-

Women’s 3000m LA 1984, YouTube. ↩︎

-

Did Zola Budd Trip Mary Decker? Olympic Distance Running Controversy, ThoughtCo. ↩︎

-

Not walking when you nick it? That’s cheating by Mark Nicholas, ESPN CricInfo, 3rd October 2013. ↩︎

-

Diving (Association Football), Wikipedia. ↩︎

-

Maria Sharapova given two-year ban from tennis for meldonium use, The Independent, 9th June 2016. ↩︎

-

Your body language may shape who you are by Amy Cuddy, TED Talk, 2012. ↩︎

-

Steve Wozniak: Apple starting in a garage is a myth, The Guardian, 5th December 2014. ↩︎

-

Garage brand: Google taps its founding myth in search of a new beginning, The Verge, 27th September 2013. ↩︎

-

The eBay creation myth and other corporate origin stories, Signal vs. Noise, 23rd July 2009. ↩︎

-

Merchants of Doubt, Letterboxd. ↩︎

-

Position on sugar taxes, NZ Beverage Council. ↩︎

-

We should follow up with executives who left jobs to “spend more time with their family”, six months later, to see if they actually did. ↩︎

-

New Zealand suicide reporting has changed, here’s what you need to know, Stuff, 18th May 2016. ↩︎

-

Dishonesty gets easier on the brain the more you do it, by Neil Garrett, Aeon. ↩︎

Related Essays

Most People

To be considered successful we just have to do those things that most people don’t.

The Mythical Startup

Can we update the fairytale version of how a technology startup becomes a success?

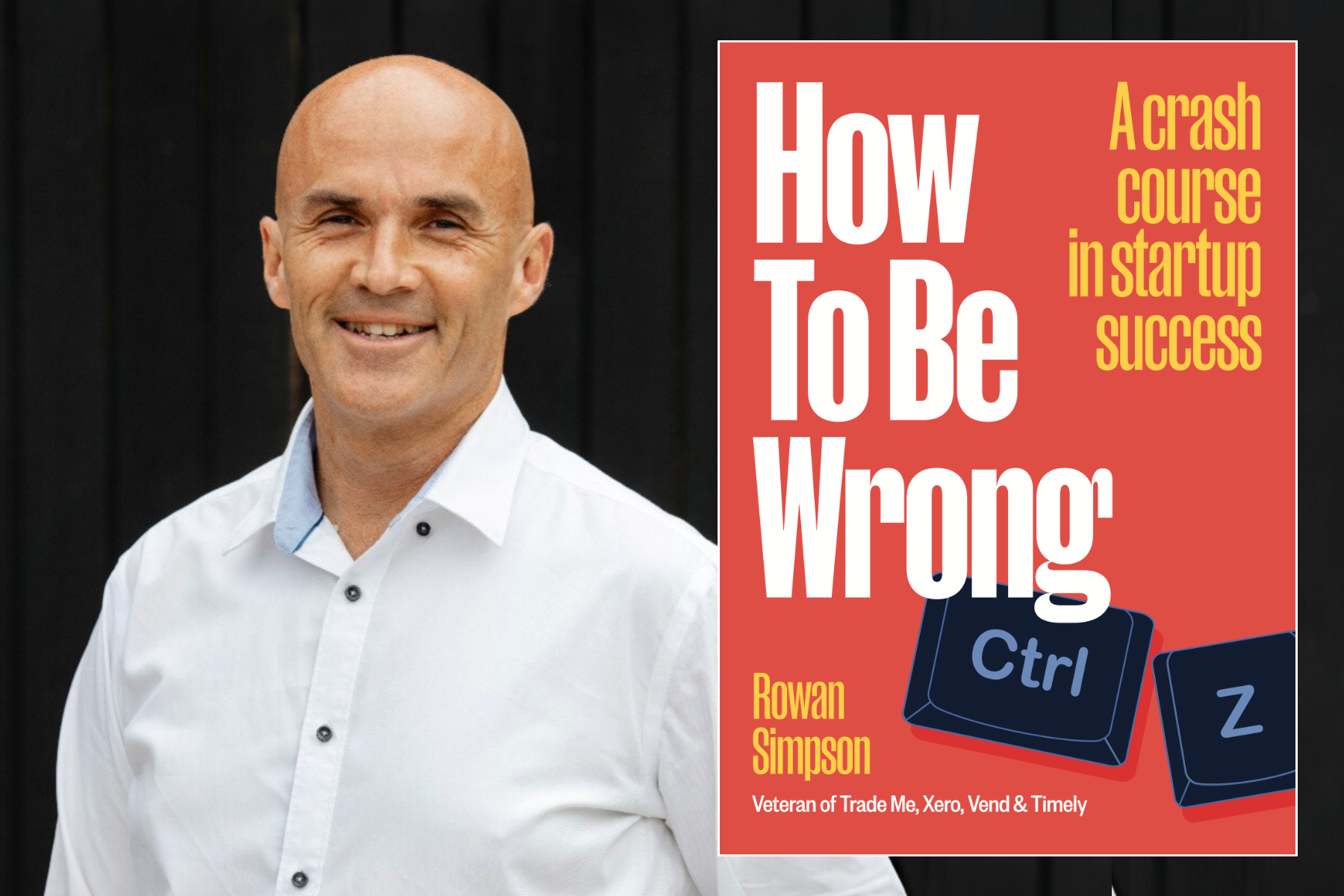

Buy the book