Every startup investment pitch deck I’ve ever seen includes a version of the same graph. When we forecast growth it’s easy to draw smooth lines that go up and to the right. But that’s not how it ever happens, in practice. We rarely anticipate the plunges – those bits have often been airbrushed out of stories of successful startups we aspire to emulate. On the other hand, when managing teams of real people, we don’t always prepare for growth that happens suddenly, in bursts. At one point in October 2014 we had 12 vacant roles advertised at Timely. It wasn’t long prior to that when the whole team numbered fewer than 12. During 2014, as we ramped up after raising investment, the Vend payroll increased from $540,000 per month to over $1.7 million per month, with office costs, equipment and training on top of that. Revenue roughly doubled too, but even so that was a significant increase to digest in a very short period of time.

One of the lessons from watching the teams at Vend and Timely expand was the recurring points when our existing ways of working were suddenly no longer suitable. Teams need to either age appropriately or fall into dysfunction.

30 People

The first common break point is when the team grows to around 30 people. This is when we need a clear organisational structure for the first time, with reporting lines and job titles and budgets and performance reviews. Which is not to say that we didn’t have or need any of those things previously; they seemed less important when the team was smaller and everybody was mostly on the same page and doing whatever was needed every day to keep things moving. For the first time, we have people in the team we don’t talk with directly every week. It starts to get difficult to keep up with what everybody is working on without conscious effort. The ratio of signal-to-noise becomes a problem and we need to start to filter. Our calendars start to fill up with status meetings. Critically, this is also when decisions that were often made unconsciously in the early days, on team culture and ways of working together, start to become embedded, for better or for worse. The course is set. If the team is a monoculture that becomes more or less impossible to change.

120 People

Things break again when the team expands above 120 people. Now it’s unlikely that everybody in the team knows everybody else by name. At this size we need several layers of management, which causes the team to fragment. This could be by function, or by location, or by tenure. It’s much more work to get the team in the same room, let alone on the same page. This is when the job of managing becomes a drag for people who are more suited to early stages. There is less need for generalists and more need for specialists. It becomes harder to vet every new hire. Inevitably we have to start dealing with performance management, which is never fun. This is also when we start to get real diversity of style. If we want to maintain a shared culture we have to really work at it rather than just assuming that everybody will pick it up by osmosis.

For Vend, when the team grew exceptionally quickly, the gap between these two break points seemed alarmingly short. We were barely back on our feet before we got knocked over again. At Timely the growth was a bit slower and more manageable. As a result, the collateral damage was much smaller.

The operating system

Another growing pain is assuming that people know how to work together. When teams are small this usually comes naturally, especially if we’ve hired people who are similar to us. But as the team gets bigger these things can’t just be implicit. The trend towards distributed teams and remote work makes this even more important. There are three layers to have in mind:

-

Hardware layer. Does everybody in the team have the equipment they need? Do we have the physical network and bandwidth installed? Do we have reliable Wi-Fi in the locations where people need to work? This layer is usually the easiest to get right. It just takes time and money.

-

Software layer. Do we have collaboration tools like Slack, Zoom and Teams that allow people to work remotely and communicate smoothly with each other even when they are not in the same physical location? In my experience, this requires constant work, as the tools themselves are not static. If we encourage curiosity, there will always be new and different ways of using them.

-

Cultural layer. Finally, and most critically, do we have the habits and techniques in place to ensure that the equipment and tools are used effectively? Have we agreed what kinds of communications are appropriate for each of the different types of tools we use? For example, what should be sent via email, what should be shared via collaboration tools, what could be a pre-recorded video update, and when do we need people to be available for a video call?

At the start of the first Covid-19 lockdown in 2020 I was asked by a journalist how I thought the internet would cope with the sudden shift to having the majority of people working from home. I said I was confident in the hardware layer and pretty confident about the software layer, but anxious about the cultural layer. I noted that the rollout of high-speed fibre connections to many places had been completed just in time. As somebody who had worked mostly remotely for five years prior to the pandemic, I knew that the software already existed and was reliable. But my expectation was that everybody would need to quickly learn the etiquette and, at least initially, would exhaust themselves by replicating familiar offline ways of working using online tools. To take one example that may feel familiar: long meetings involving one person talking and everybody else listening. Painful enough when everybody is in the same office, and deadly when everybody is on video.

It’s useful to think about collaboration challenges in layers. It helps us quickly identify where the actual constraints might be and narrow in on possible solutions. Getting one or two layers right isn’t enough. To have a team that works well together we need all three. And just when we think we have it solved, the team grows and we have to start again.

Skip?

An exercise I recommend to help navigate these break points and growing pains, regardless of the team size, is to imagine the organisation chart when the team is three times larger. Draw it on a whiteboard. Don’t worry about putting names in each box, or providing detailed job descriptions. Think about what different functions or roles will be required when the team is that size. To do this we need to think about the business model that will sustain the team at that point as well as the funding that will be required to get there. This is a great way to tease out the the unit of progress to discuss with potential investors.

I did this numerous times with both Vaughan and Ryan over the years, as the Vend and Timely teams grew, and with many other founders since. Having watched so many people struggle with it, I know this seemingly trivial exercise is anything but.

For a team of five, it’s hard to imagine what another 10 people might do. How will the current jobs split? Likewise for a team of 20 people, imagining the structure when there are 60 in total can be difficult. What sub-teams will form? Who will lead and manage, and how many people will report to each of them? Two areas that are often overlooked are HR and finance (the “company” part of the the three machines). In a very small team these are jobs that everybody does, and so nobody does. But as the team grows they become separate functions, and are vital to fuelling the growth itself. Another common point of tension is the split between product, marketing and sales, and within the product team the split between engineering and operations. Again, in a smaller team these are functions that are typically shared between multiple people where everybody does a bit of everything. We should keep an ear out for team members describing others as “they” rather than “we” and talking about “the business”, as if they are not part of the business themselves, and remind them: we’re not stuck in traffic, we are traffic.

After drawing the boxes we can start to think about the existing people we have in the team today and how they might fit into that future structure. Where are the gaps? Where do people need to evolve their role or start to specialise? Who will still be excited to be part of the team at that size and who is likely to want to move on at that point?

Once we’re done, then do it again, but this time imagine the team when it is five times as big as it is now. This will highlight a whole new layer of complexity.

The question I love to ask when any founder asks for advice about their startup, is: what is the constraint? It’s a useful shortcut to digging into specific areas of the business and to understand what could unlock growth. For many years the noise from founders complaining about how difficult it is to find investors has drowned out the much smaller but ultimately much more interesting group of founders who successfully raise investment and, as a consequence, bump into a whole different set of constraints.1

When I ask them what’s holding them back the answer is nearly always related to the challenges of finding and keeping great people – how to manage their existing team so they perform to their potential, and how to grow their team without wrecking the culture. Raising capital allows founders to create new roles, but filling them with capable people and keeping them filled is still hard work, and cash is only one part of the solution. It’s tempting to think that startups are mostly about having a great idea, but in the end they are about being great at recruitment and even better at retention. That’s execution.

The good old days

The present moment looks different depending on where in time you look at it: it was once the unthinkable future;2 one day it will be the distant past.3 A few years after Trade Me was sold, I bumped into somebody who joined the team shortly after I had left. I asked them how it was going. They complained that the culture was changing. The implication was that it was no longer as enjoyable to work there as it had been previously. I nodded sympathetically, but thought to myself: change like that is endemic.

One of the mistakes we often make when thinking about startups is imagining them to have a steady state. It’s not that they one day change. They are constantly changing and continue to change as they grow. Like all of us, teams also only get to be each age once. This churn can be invigorating but also exhausting. Rapid growth isn’t a natural state for a company. It’s always fleeting. Most things that grow really quickly are bad things – cancers, viruses, wildfires. To keep fast growth under control and make it a positive experience requires careful curation and constant attention. It doesn’t just happen. We have to repeatedly break things to fix them. If we think a few moves ahead then we can adapt and get to the next level. Then to the one beyond that.

If we have the opportunity to work on something that grows fast, like Vend did and as Timely was starting to by 2014, we need to appreciate it in the moment. It’s difficult, maybe impossible, to see it when we’re in the eye of the storm, but those are the good old days we’ll reminisce about.

-

This tweet of mine, from 2014, remains frustratingly evergreen:

↩︎Stop thinking that capital is the constraint to more high-growth Kiwi companies. Every company I’m invested in can’t hire enough people.

-

Stewart Brand, Twitter, December 2015:

↩︎This present moment used to be the unimaginable future.

-

Andrew Schelling on Gary Snyder’s “This Present Moment: New Poems”, by Jerome Rothenberg, Jacket2.org. ↩︎

Related Essays

How to Scale

What a founder in one of the poorest areas in Kenya taught me about how to start and how to scale

The Plunge

Why do the most interesting bits of startup stories always get airbrushed out?

Machines & Phases

There are so many different ways to measure a startup. It’s easy to drown in metrics. How do we separate the signal from the noise?

Unit of Progress

Be specific: Where are we going and what will it take to get there?

Hockey Stick Growth

It takes a long time to become an overnight successs. But to get there we need to be growing from the beginning.

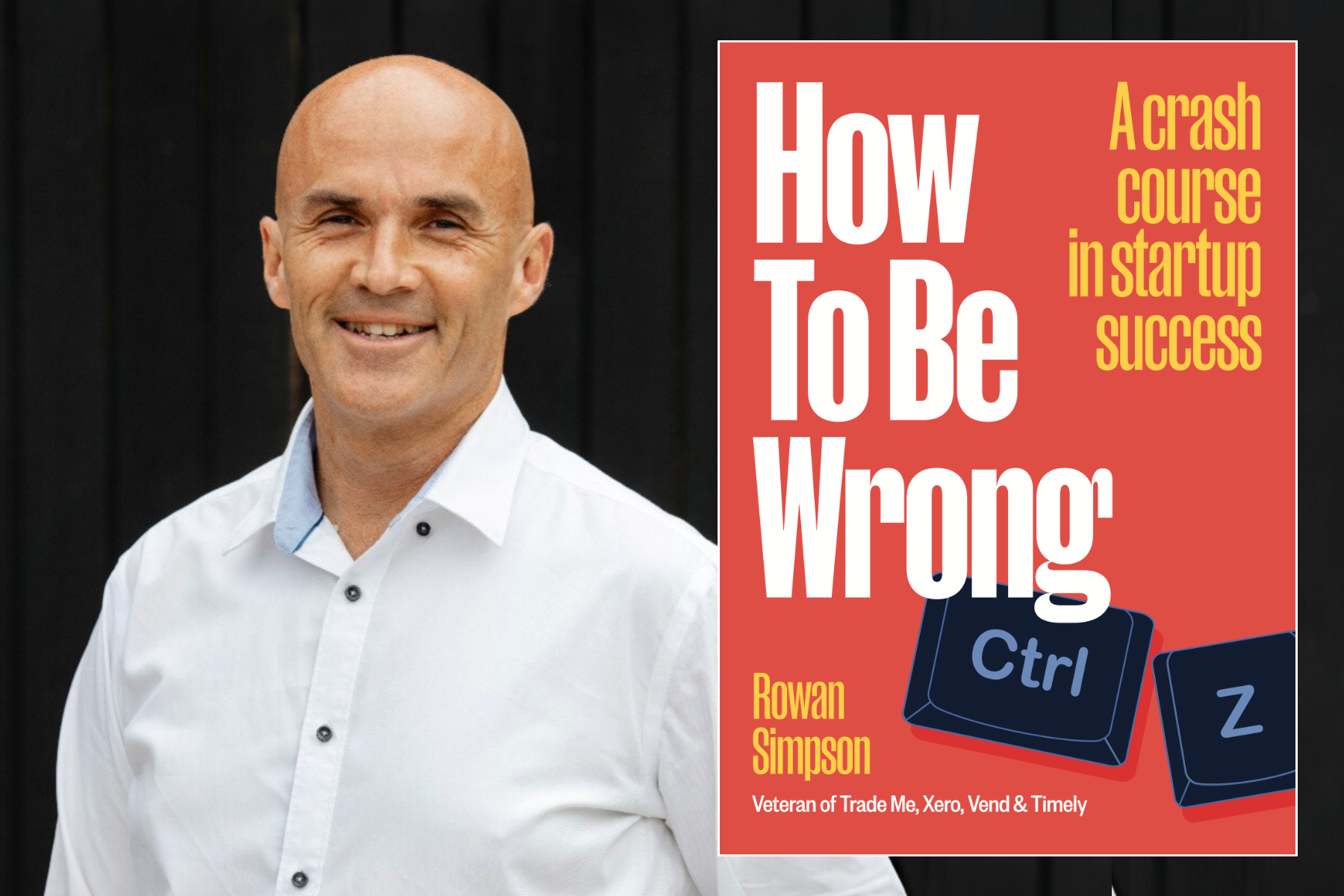

Buy the book