History isn’t fact. It’s narrative.

When a startup business is a huge success it’s easy to focus on the end point, and forget about the route. When the stories are re-told over and over, details get re-written or forgotten. And the bits that are omitted and updated are nearly always the stumbles or backwards steps.1 As a result, others starting out on their own venture never hear about these hard moments, and so don’t always anticipate that it might happen to them too. The biggest deceit is thinking that it won’t.

I’ve worked on and invested in some of New Zealand’s most successful startups. They have become iconic companies. But I got to know each of them at the very beginning, when their success was far from obvious. I was an early employee at Trade Me and Xero and, thankfully in both cases, also a shareholder. The financial success of those companies enabled a second act in my career as an early-stage investor and advisor at startups like Vend, Timely and many others.

There are entertaining tales to tell about all of these companies, and a handful of days that were wonderful - in a couple of cases life changing. But those moments are the rare exceptions. The experience of actually building these companies is much more about the long, hard grind well away from an audience than it is the magic moments in the spotlights. And far more often repeated and frustrating (not to mention expensive) small failures than glorious victories. Frankly the honest inside stories would be tedious dull tragedies rather than epic heroes’ journeys.

Aside from the fact that I worked on all of them, one of the few things Trade Me, Xero, Vend and Timely have in common is that they all experienced significant near-death moments…

2001: Trade Me

Trade Me was only two years old and still quite fragile. In just 18 months our small team had signed up over 100,000 members. We were hosting over 1,000 auctions every day. We were adding features to the website as fast as we could imagine them. That was exhilarating. But the original business model (free online classifieds, supported by advertising) had failed to generate any significant revenue to fuel further growth.

We’d spent all the money that had been invested. The founder, Sam Morgan, pitched the company at a distressed valuation to all of the local venture capital funds that existed at the time, and most of the large corporates. They all said “no thanks” (actually “thanks” wasn’t always part of their response). The dot-com stock market bubble had burst and would-be investors were deeply sceptical about the potential of internet businesses. In the meantime, the company was being propped up by loans from existing shareholders.

I had only recently become a shareholder myself. I didn’t have any cash to lend, but I did work for several months at a significantly reduced salary, before that became unsustainable. The lure of highly paid work overseas eventually became too much. If I’m honest, when I left, I didn’t expect there would be anything to come back to. I was 25 years old. Perhaps my startup phase was over?

I wasn’t the only one. Three of us from the original team of four left in quick succession, including Sam and his sister Jessi, who was the first employee before me. At one point, all three of us were living and working as contractors in London, leaving the fourth, my old friend Nigel Stanford, running things more or less by himself back in New Zealand. That period of time has never been properly documented, perhaps because it doesn’t fit the preferred narrative of constant growth and success.

One of the last changes we made to the website before I left was to start charging sellers a small compulsory “success fee” on each completed sale. It wasn’t so much that we realised this was the golden ticket - more that we’d run out of any other options to make money, so had nothing to lose. Within a year or two this would fuel a lucrative business model.

Within a few years Sam, Jessi and I all returned to executive roles in the business. In 2006 the company was sold to Fairfax for $750 million.

That outcome wasn’t obvious at the time.

2008/2009: Xero

Some people, especially Australians, think that the Xero story started around the time of the listing on the ASX at the end of 2012. The share price then was A$4.65, and by early 2014 it had jumped to over A$45. But there is a long pre-history prior to those glory days, where the share market wasn’t nearly as positive and the outcome for the company was much more uncertain.

I invested and joined the team just prior to the initial public offering (IPO) on the NZX in 2007. That listing valued the company at $55 million, and raised $15 million of new capital at $1 per share. For several years after that the share price languished below that listing price. In public, at least, co-founders Rod Drury and Hamish Edwards were full of bravado. But despite the stated global ambitions, there was pretty modest customer traction, almost entirely in New Zealand.

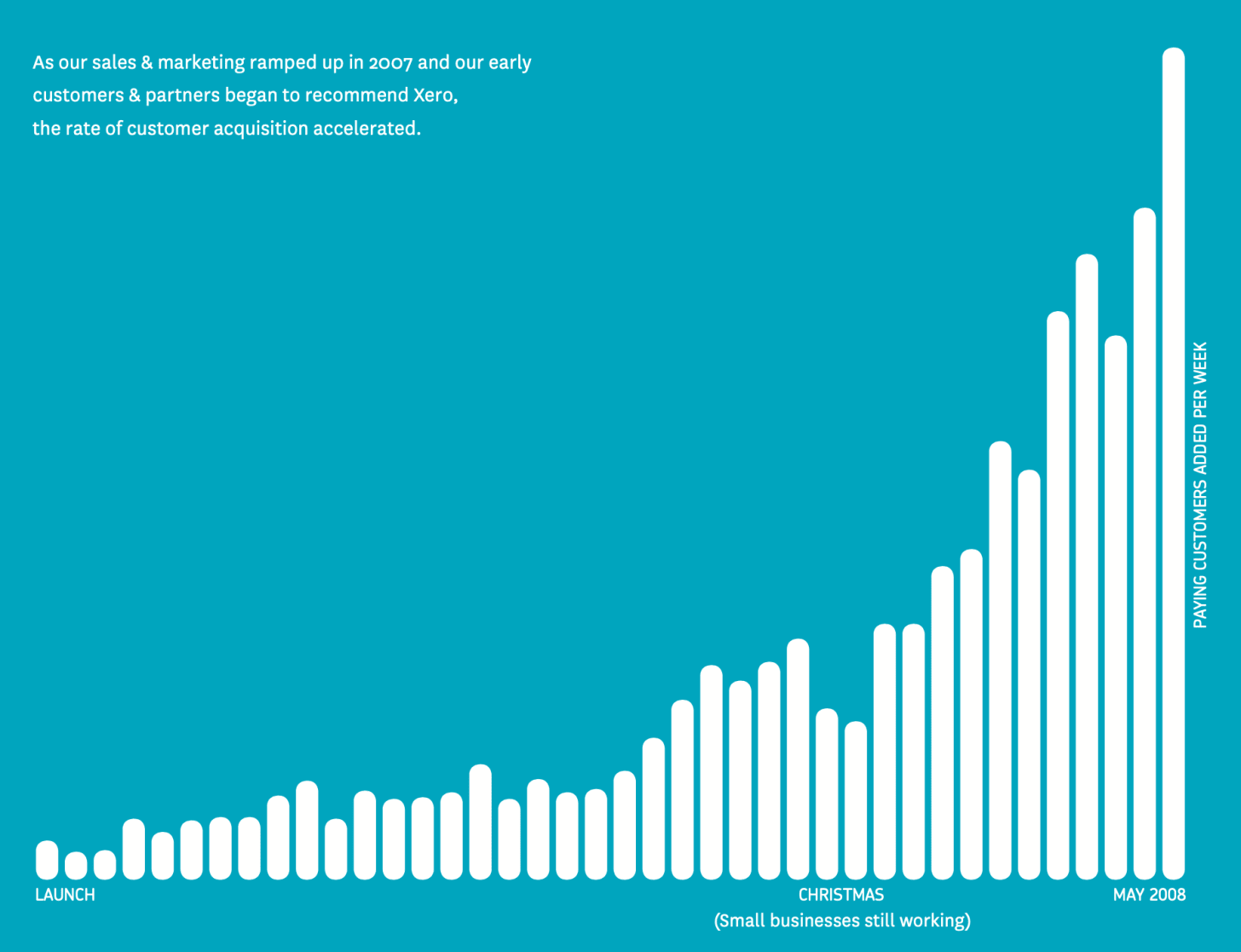

The IPO prospectus forecast that the company would have 1,300 subscribers by May 2008.2 The actual result we achieved was 1,408. Although as this graph from the first Annual Report shows, a good percentage of those new customers signed up in the final few weeks.

The total subscription revenue for that first year was just $134,000. The company made more money from interest paid on the unspent IPO funds. It was an anxious time.

The large well-paid team were burning through cash quickly. It wasn’t obvious that the stock market would be patient long enough. One analyst speculated that we could be the first public company to be named after our share price.3 There was a high turnover of senior staff during this time, especially sales and marketing related roles. I was one of those who left. Thankfully, I didn’t table flip completely and sell my shares on the way out.

In 2009 the company raised $23 million of new capital from MYOB founder Craig Winkler.4 MYOB was the incumbent accounting software provider that Xero was hoping to disrupt in both New Zealand and Australia. Craig had only quit as CEO a year prior to that after MYOB shareholders had blocked his share option grant.5 It’s mostly forgotten now but his purchase price was 90c per share (i.e. 10% below the IPO price from two years earlier) and after that investment he owned 24% of Xero.

Around the same time, the sales team led by Leanne Graham shifted to focus on selling to accountants rather than directly to small businesses. With the benefit of hindsight, that was a turning point. Within the next three years Xero raised a further $170 million of capital, the number of subscribers increased from 6,000 to 78,000 and revenue increased 20x. Now it has millions of subscribers, is valued at over A$10 billion, and hasn’t looked back.

That outcome wasn’t obvious at the time.

2015: Vend

I was one of the original investors in Vend in 2010. To even call it a company back then was slightly misleading. It was really just a founder, the magnificently moustachioed Vaughan Rowsell, and his wife Mel. They had an idea to build cloud-based point-of-sale software for small retailers. In the crazy five years that followed we had raised over $35 million of capital from international venture capital funds. We had hired nearly 250 people. We were a global business, with just 15% of our revenue coming from New Zealand. Our customers included ice cream stores in Russia and garden supply stores in the Cook Islands. We had won both Emerging Company and Exporter of the Year at the recent Hi-Tech Awards, and ranked 4th on the 2014 Deloitte Fast50 list of fastest growing companies in the country. We were expanding at an eye-watering pace, but also still burning significant amounts of cash every month. By the end of 2015 we came very close to shutting the company down.

We had signed a term sheet with a potential new investor who then changed their mind at the very last minute. This left us with some hard decisions to make and no time left to make them. Because we were spending much more than we earned we were “default dead”.6 We had chosen a growth path that required us to get permission to continue to exist from investors every 12-18 months, and our time had suddenly run out.

When this all unfolded, I was in Berlin, with fellow director Barry Brott from Square Peg, an Australian venture fund and our largest investor, and Kimberley Gilmour, our Head of People & Culture. We had intended to meet the new European sales and support team we had recently hired, but instead we spent the day informing them that we would need to close the office and they would all be out of a job.

I tried to track down Vaughan, but he was missing-in-action. So from our hotel in Prenzlauer Berg, in the former East Berlin, Barry and I spent the night on a series of urgent phone calls with existing shareholders, trying to confirm further funding. Not surprisingly, there were a range of reactions. I got some very direct and not very complimentary or constructive feedback on my performance as Chair of the Board from some of them. Finding consensus in that environment was tricky. By the time we finished speaking to everybody it was the early hours of the morning. We decided to head out for some food, and got flashed by a drunk German teenager in the hotel elevator. I was too exhausted to do anything other than laugh at him. I don’t think that was the reaction he was expecting.

A couple of days later I flew back to Auckland and checked into the only-just three-star Quest Apartments in Newmarket, just down the road from the recently refurbished and suddenly much too large Vend headquarters. There were a number of further difficult decisions waiting in the following days and weeks. We had to urgently reduce the team size, and make a number of people redundant, including some who had worked in the business for a long time and done the hard yards. That was painful for everybody. Anybody who thinks it’s difficult to grow a successful startup should try rapidly shrinking one. It’s much harder.

Somehow the remaining team found a more sustainable path forwards and we eventually confirmed new funding, mostly from existing shareholders. Within a few months there was almost an entirely new exec team and board (Barry was the only survivor) but the business continued.

In 2021 Vend was acquired by Lightspeed, one of our fiercest competitors from back then, for $485 million.

That outcome wasn’t obvious at the time.

2020: Timely

Timely was nearly one of the first startups to fall victim to the COVID-19 pandemic. I’d been involved since 2013, when co-founders Ryan Baker and Andrew Schofield (known to us all as Scoff) had convinced me to become their first investor. They were not typical founders. They were quietly confident, considered and measured. More than any other founders I’ve worked with, they were always keen to listen and adjust based on the advice they got. We never got ahead of ourselves.

However, as the virus started to spread around the world, in early 2020, the vast majority of our customers (hairdressers, beauty salons, spas etc) were suddenly shut. We watched forward bookings evaporate as the world went into isolation. It was obvious this was going to be a real test for all of us. Rather than hide from that fact, we shared the data publicly. I know many people in the health and beauty sector found that incredibly useful as they worked on their own response.

We took the same approach internally. The impact on our subscription revenue wasn’t pretty. We had no idea how much longer this would continue, but the forecast bank balance trended pretty quickly to zero. We shared metrics with the whole team showing the revenue impact and the amount of cash we needed to stay afloat. Giving everybody the information they needed to make good decisions was key.

We had to immediately bury our old plans. That required remarkable leadership. Ryan, who with his executives had spent the last few years building an impressive team, committed to preserving every job. We offered generous discounts to customers. We immediately cut board fees to zero and made deep cuts to executive salaries, and then asked the rest of the team what they could do to help. He described the approach to everybody: 7

All of us will be affected a little so that none of us has to be affected a lot.

Overall, we reduced the already lean cost base by 20%. Some staff agreed to bigger cuts so that others, who would be more heavily impacted, didn’t have to. It was an amazing collective response. This created a positive feedback loop. With job security, the whole team focussed on helping customers navigate the lock downs, providing whatever support we could. We retained the bulk of our customer base, albeit on reduced subscriptions. Because many competitors were missing-in-action during this time we even gained market share. That additional revenue allowed us to keep the cycle going.

Remarkably within a few months we were able to repay staff the salaries that had been cut. And shortly after that we started the conversations that would eventually lead to the sale to EverCommerce. One of the terms of that sale was that the wage subsidy we’d received from the New Zealand government was also repaid, which was a nice full stop to this phase.

That outcome wasn’t obvious at the time either.

Hold on tight

Dips like these cause whiplash for founders. A startup condenses intense experiences and changes people. These moments are stressful and it’s not uncommon for that to break relationships. Only a handful of my former colleagues remain close friends. That shouldn’t be surprising.

Dips are the moments of truth for investors and advisors too. It’s easy to support a successful company. When things go badly it separates people who are willing to roll up their sleeves and help from those who are just along for the ride. Normally these are expensive lessons for those investors who continue to believe and are prepared to step up in the short term. But also the most rewarding, in both senses of that word, when it works out.

Because they were all very successful in the end, it’s easy to dismiss Trade Me, Xero, Vend and Timely as outliers. But that misses the most important thing I learned from working on all of them: none of them were obviously successful in the beginning, and all of them felt like imminent failures at many stages in the middle. I have some negative personal mental scar tissue from each of those stories. Amazingly, they all had happy endings.

It doesn’t always work out this way.

-

This was really highlighted to me when I watched The Social Network movie about the early stages of Facebook. In one scene they are a small team struggling away in a house in Palo Alto, and nobody has heard of them. Then, it jumps quickly to them moving into their first office and celebrating 1 million users. As if that just happened while they weren’t looking! I couldn’t help but feel like they just skipped over all of the most interesting bits in the story, in a montage. ↩︎

-

Xero Live Limited - Share Offer Investment Prospectus, 2007

The prospectus also estimated that the average revenue per subscriber (APRU) would be $75 (it’s been consistently between $25 and $30 ever since), and contained this wonderful underestimate of the breakeven point:

↩︎Dependent on pricing, the Directors assess, based on their current estimates of Xero’s cost base, that Xero’s New Zealand revenue will begin to exceed its New Zealand cost base at around 8,000 customers. However, Xero will also be investing in the development and growth of the business and pursuing expansion of the business into the UK and Australia. Therefore, the Directors do not currently expect that Xero will record an overall profit for at least three years.

-

Xero (XRO.NZ) – Thoughts on Valuation, Clare Capital, 3rd October, 2013. ↩︎

-

MYOB founder buys into rival, Sydney Morning Herald, 7th April, 2009. ↩︎

-

MYOB shareholders vote down options allocation, Sydney Morning Herald, 25th April, 2008. ↩︎

-

Default Alive or Default Dead?, by Paul Graham. ↩︎

-

Ryan Baker, Twitter, July 2020. ↩︎