I got some excellent advice from a former manager, back in what my kids call “the 1900s”, when I still wore a suit and tie to work and starting my own company hadn’t yet entered my mind. I wasn’t enjoying the work and started to think out loud about quitting. He took me aside and said:

I’m not going to try to convince you to stay, but don’t quit because you’re frustrated, leave because you’re excited about what you’re going to do next.

Thankfully, I took that advice and stayed on the project. I spent the next six months or so thinking about what I wanted to do instead. The decisions I made during that time have shaped the rest of my life.

I’ve subsequently given similar advice to several founders, trying to decide if they should shut down or sell their company. Often the question of an exit has only come up because they have lost their enthusiasm and they are feeling exhausted. More than once I’ve said:

Don’t sell the company because you’re tired. Sell because you’re excited about what you can do with the proceeds - at least more excited about that than what you’re currently doing with the team and product you have.

Worse than failure

I’ve learned that most founders gravitate to binary thinking: a venture is a success or a failure, with the needle oscillating between the extremes on the dial several times in the course of a single day, depending on how things are going. However there is a third outcome which is worse than failure: a venture that is living dead. Most investors in early-stage companies will be familiar with this description, but unfortunately founders often don’t realise when theirs is one.

Here are some features of a textbook living dead venture: It has some customers, and associated revenues, but few if any who really love it. Because people don’t feel strongly, one way or another, it’s difficult to get any feedback. Product work crawls to a standstill because designers and developers can’t get excited about toiling away on something that hardly anybody is using. People don’t find it remarkable, so don’t tell their friends. It may even have a bunch of customers who stick around purely out of loyalty to the founders or because they are embarrassed to admit they don’t use it. This can be hard to believe, until you see it happening – it’s like the absent gym member who can’t bring themselves to quit because that would mean that their commitment to getting fit is officially over.

The venture is bringing in enough money that it seems silly to think about shutting it down, but nowhere near enough to attract further investment to drive growth, and probably not enough to properly pay people for their time. By default it trundles along the same path, accumulating sunk costs. As cash burns down to below subsistence level the company is effectively driven down a narrow dead-end street, because there is no longer enough money left to spend on trying different things to turn it around.

It operates mostly in the dark. The founders stop looking at the numbers, because they’re depressing. Faith starts to trump facts in decision-making. Investors don’t get any updates, because founders are waiting on fortunes to change so they can give an upbeat assessment (this always seems to be just around the next corner).

Most tellingly, it has no momentum. It atrophies. It moves forward only when the founders or investors push it. And progress, when that happens, is never in proportion to the investment of time and money – working on it is like running in soft sand.

Whenever we find ourselves in this position, as a founder or as an investor, we have a difficult but important decision to make.

Call it a day

It’s tempting to think of a startup as our child, hoping it’s just going through a phase and that success is just over the horizon. After all, in theory if we can just avoid dying we win.1 But this is not about the hard patch that every successful startup seems to have to go through at one point or another. This one has never really fired in the first place.

Because so few early-stage companies are profitable it can be difficult to tell from the outside if any venture is on track or not. When we are on the inside, we have to honestly assess whether we can get to the next milestone with the resources we have, be that cash-flow breakeven or raising more capital. As soon as we lose that confidence we’re living dead. The “rocket ship” metaphor, while often just bravado, is useful: all startups aim for the stars but few reach orbit. Without another booster stage to fire, once our momentum runs out, it’s already over. Gravity eventually wins.

Once we admit that we are living dead, we need to forget about the sunk cost and get our head around the opportunity cost of investing more time and money into a zombie venture. Other successful startups that constantly struggle to hire enough good people would be delighted to have our experience. What might seem like a brave decision is, in truth, a logical choice. It’s better to have already failed than to be plodding on. A startup is an unbounded commitment, and in any life there is only room for one of those at a time. So when it’s obvious we’re done, we should call it a day. Then get on with the next thing. Who knows, the next thing might be the next big thing.

Headline Inspiration: Dead Parrot Sketch, Monty Python, 1969

-

How Not To Die, by Paul Graham, August 2007. ↩︎

Related Essays

M3: The Metrics Maturity Model

Use these simple steps to improve how we measure and report our progress.

Long Enough

How would treating time as a variable that we can influence change the way we behave and the choices we make?

The Plunge

Why do the most interesting bits of startup stories always get airbrushed out?

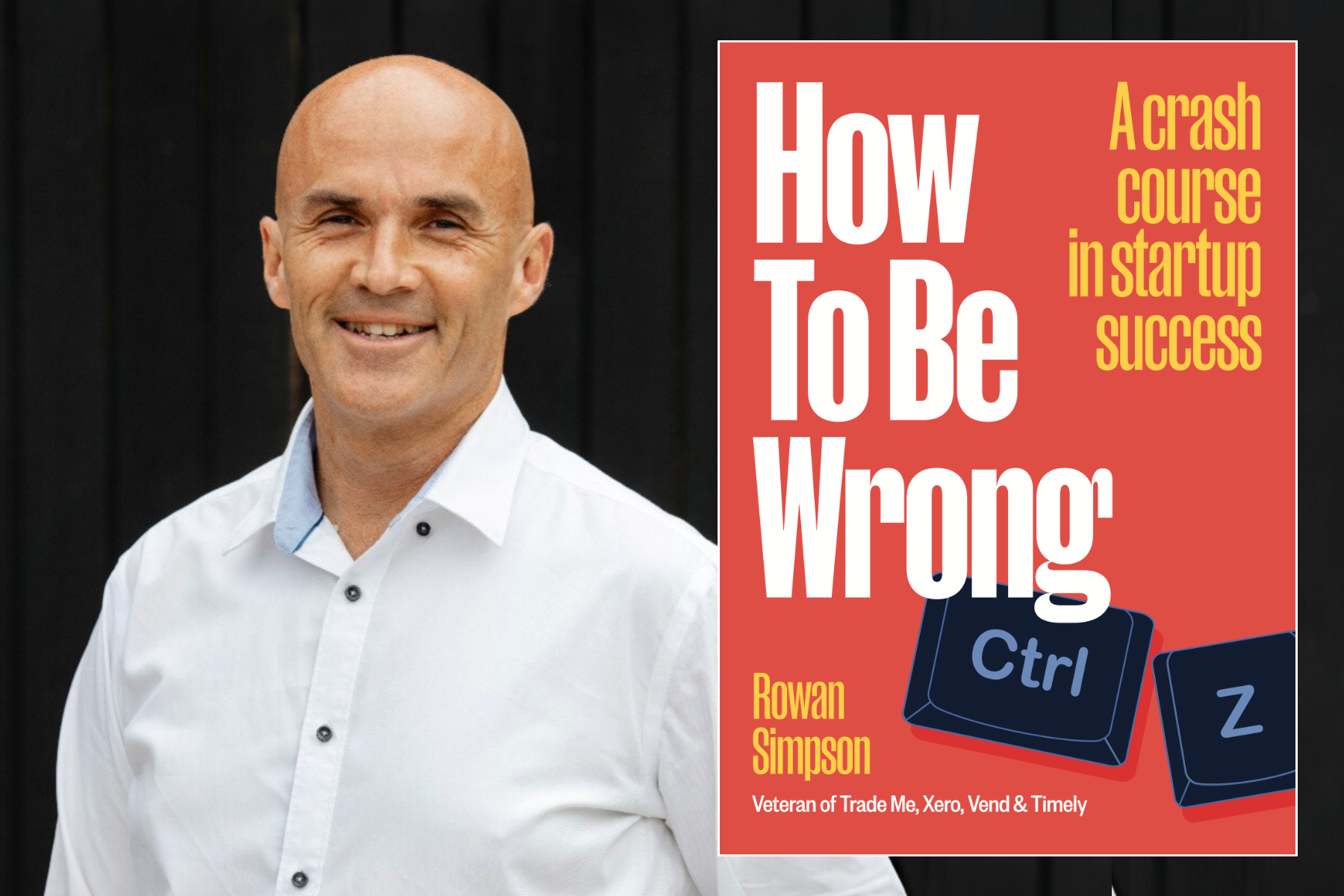

Buy the book