I don’t recall what convinced me to attend. Spending an evening listening to a physicist talk about prosperity doesn’t sound like my idea of fun. And yet, there I was, on a cold Wellington evening in 2011. I rushed up the stairs at Te Papa, and quietly grabbed a seat near the back of the theatre just as the speaker was introduced.

“Tēnā koutou,” he said tentatively, conscious about his vowels. “Ko Paul Callaghan toku ingoa. We don’t think about the future terribly well in New Zealand.”

I knew right away that this wasn’t going to be a normal physics lecture.

That short talk has had an outsized impact on New Zealand. Only a small group of people attended in person and only slightly more than that have ever watched it online.1 But a much larger audience has enthusiastically adopted his memorable catchphrases, and they’ve shaped public policy in important ways (although probably not as he intended). You may be surprised to discover exactly what Sir Paul Callaghan actually proposed back then.

Callaghan was the founding director of the MacDiarmid Institute at Victoria University in Wellington. During his academic career he published numerous papers and articles in the area of molecular physics. But he also put theory into practice as the founder and director at Magritek, a business that manufactures nuclear magnetic resonance and MRI instruments. He was a regular public speaker, including a science slot on Kim Hill’s weekend radio show, and in 2011 was honoured as Kiwibank New Zealander of the year.

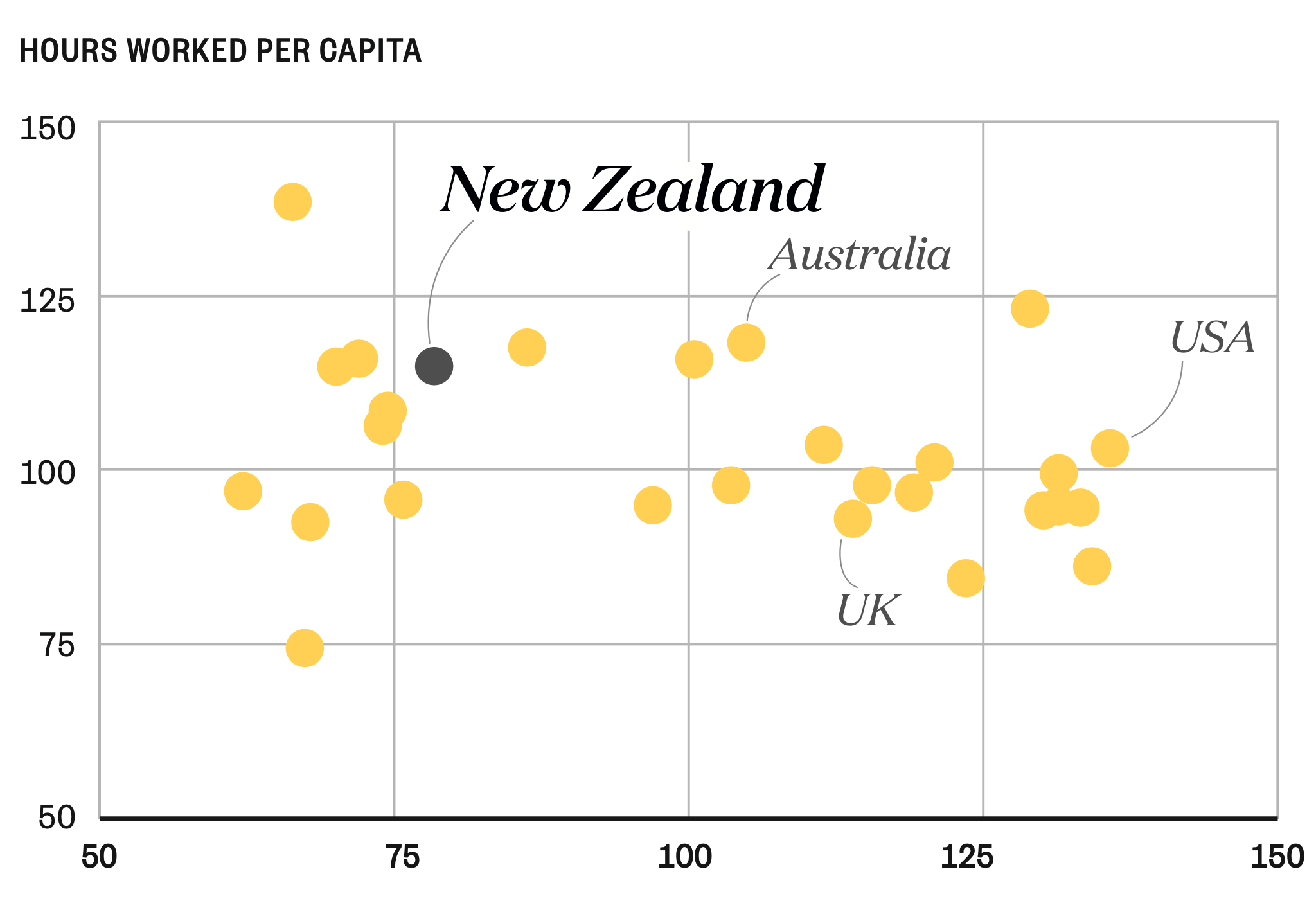

Callaghan’s primary concern was our place in the world. He showed that New Zealanders work longer and harder than just about anybody, but earn less per hour than nearly all other countries we compare ourselves to. This was true then and it’s true today. This was a very personal point for Callaghan. He had recently been diagnosed with cancer. He explained that prosperity is what allows us to afford the things we all want more of, like new drugs, better hospitals and skilled people to work in them. His prescription was simply stated. He said we needed more companies that generate high revenue per employee (unlike tourism), and without negative environmental impacts (unlike dairy farming). He counted the revenue earned by the largest software and manufacturing companies that existed at the time and extrapolated. He suggested we needed a hundred more like them. He identified that creating and sustaining these companies would depend on highly skilled and highly sought-after people. If we wanted to attract and retain them, New Zealand would need to be a place where talented people choose to live and work. Ironically, given the things to which we’ve subsequently attached his name, he explicitly warned against picking favourites. He said that these businesses would be unpredictable. He anticipated that our competitive advantage would be in obscure niches, and that the companies that were eventually successful would surprise us.

He was right about all of those things.

Callaghan shared some big ideas that night. For me, the biggest lesson was his style of presentation, which reflected his style of thinking. He described our common beliefs, exposed the flaws and (importantly) in each case proposed a different, better way of thinking. He didn’t just give the correct answer (from his perspective, at least); he explained why previous assumptions were wrong.

With that in mind, let’s revisit the seven common myths that he spoke about that night, with the assistance of the latest data and the benefit of hindsight, and think about how his message might have been updated, if he were still with us to do that…

1. New Zealand is an egalitarian society

Callaghan started with an idea we hold dear in New Zealand, even if in recent years we’ve become a little more honest about the reality. He quoted income inequality data, calculated using the Gini Coefficient, where higher values indicate higher inequality. In 2010 the value for New Zealand was 0.32. Only seven of the 33 “rich” countries in the OECD rankings had greater income inequality.2 In 2020 the value was still 0.32 – so there wasn’t any material change during that decade.3 In fact it’s been the norm for a generation – we have been in that range since 1992.4 As for international comparisons, the most recent OECD data ranks us 23rd out of 37 countries, slightly behind Greece and Portugal.5

In other words, despite what we think, nearly all the other countries that we like to compare ourselves with are still more egalitarian than us.

2. New Zealand is “clean and green”

When Callaghan was speaking in 2011, there was a lot of discussion about the validity of the “100% Pure New Zealand” message used by Tourism NZ, and how much economic output contributes to that.6 John Key, who was prime minister at the time, would later say that the expression 100% Pure was like a fast food ad and should be “taken with a pinch of salt”.7 The specific example Callaghan referenced to describe this myth was the impact on water quality from increased dairy farming. I wonder what he might have said then if he had known that by 2023 the output from dairy farming would increase by a further 20% (from 17.3 billion litres of milk to 20.7 billion litres).8

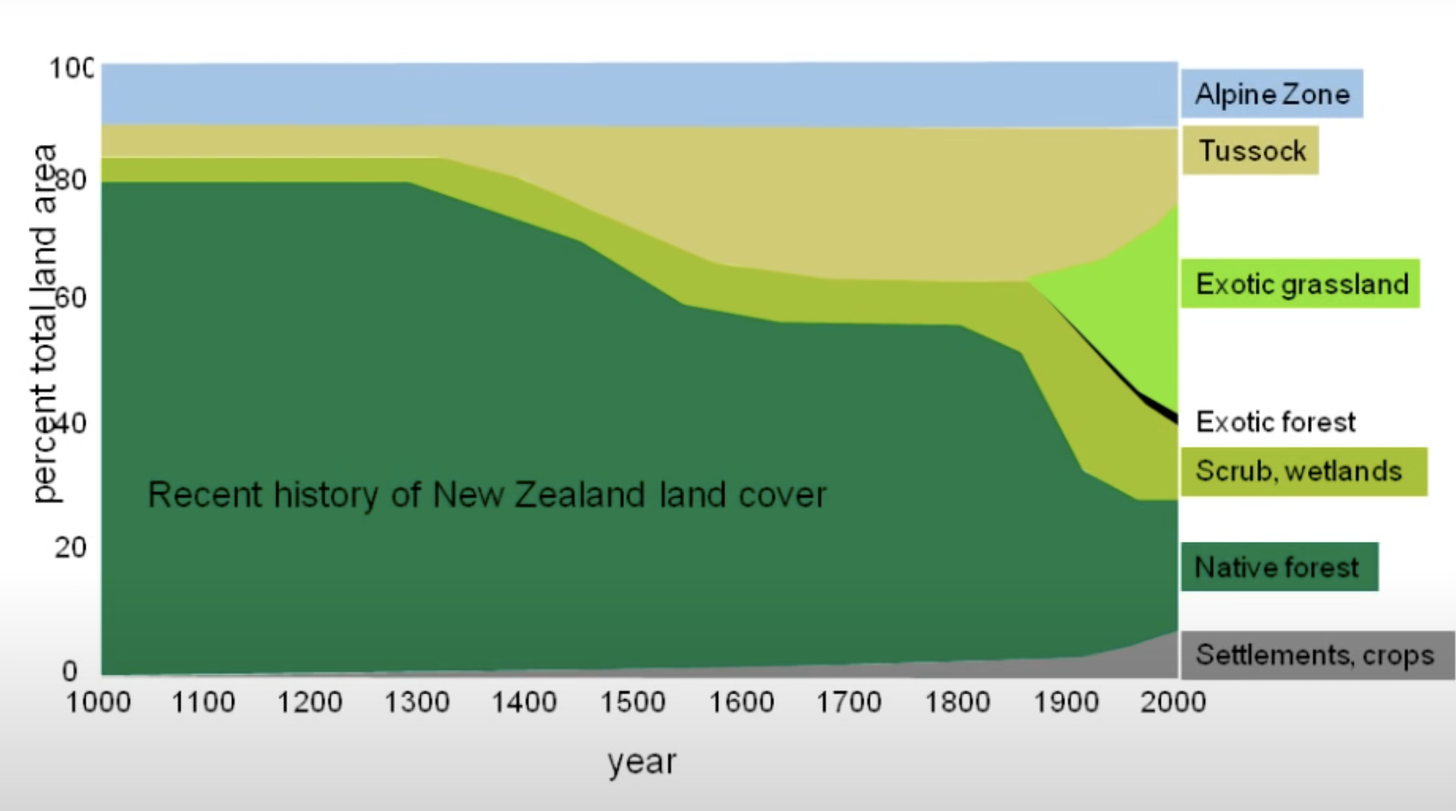

He also pointed to this graph that highlights the hypocrisy of expecting developing countries to be more respectful of their environmental impact now, when our own history in this regard is poor, especially from 1800 onwards:

That remains very topical today, although the media focus has now shifted away from our marketing messages and more towards our actual response to climate change.

3. We don’t need to be more prosperous

Callaghan mocked people who are dismissive of our declining prosperity:

We don’t need to be rich like those Australians

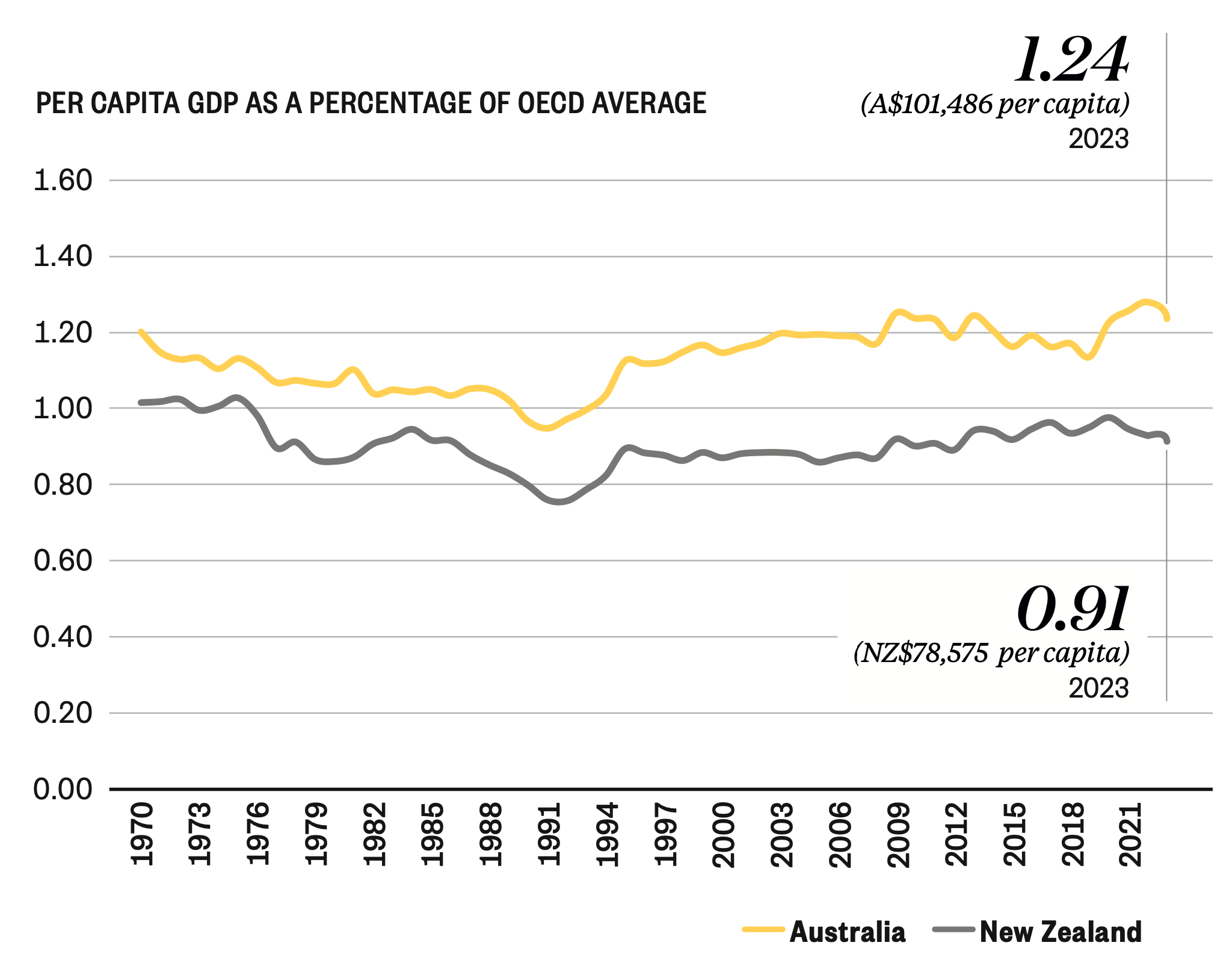

He explained that prosperity is what allows us to fund the things we all want more of – better schools, hospitals, roads and connections to the rest of the world. And many other things. He specifically focused on the income gap with Australia. In New Zealand we love a flattering per capita measure of success. Unfortunately, our per capita GDP compared to the OECD average is not one of them. Here’s an updated version of the chart that Callaghan used in his talk:

I was born in 1976, which is the last time that New Zealanders earned more per capita than the OECD average. By 1992 we had fallen to only 75% of the OECD average. The gap with Australia at this point was already over 20%. Since then we have struggled to catch up – even as both countries have improved relative to the OECD average in recent years.9

In 2010, Callaghan calculated that to match the prosperity of Australia, New Zealand would need to earn NZ$45 billion more per year. This may have been an underestimate.10 What’s happened since then? In 2023 Australia earned A$101,486 per capita (124% of OECD average) while the equivalent in New Zealand was NZ$78,575 per capita (91% of OECD average). That means during those 13 years the gap has grown to NZ$155 billion in total.11 However we calculate it, the gap continues to be substantial.

Callaghan was speaking in the wake of the Christchurch earthquakes, and he specifically highlighted the predicted cost of the rebuild as “severe”. It’s chilling to think that the government portion of that rebuild was $7 billion, compared to the $50 billion the government allocated in 2020 towards the Covid-19 response and the $42 billion earmarked for new infrastructure spending in the four years after that.

There is a lot of work to do.

4. We have a relaxed easy-going lifestyle

(a.k.a, to be more prosperous we’d need to work harder)

This is the most confronting statement Callaghan makes in the talk:

We are poor because we choose to be poor

What did he mean? That we choose to own and work in businesses that require long hours for little output per hour worked. He showed we worked longer than just about anybody, but earned less per hour than nearly all the other developed countries that we compare ourselves to. What has happened in the years since?

Sadly there has been no improvement. In fact, we now work even harder than we did then, and with only a marginal improvement in output per hour. The key to improving our prosperity isn’t working harder.

We are still poor because we choose to be poor.

5. More tourism would benefit the economy

Next, Callaghan broke it down by sector, to attempt to understand the component parts. To do this he calculated the revenue per employee required to maintain the then current levels of GDP, and came up with $120,000 per job (or, more accurately, per full-time equivalent employee, or FTE).12 He compared that average to the values for the two biggest sectors: $80,000 per FTE for tourism and $350,000 per FTE for dairy.

The two lessons he drew from this still feel very contemporary.

First, it’s a mistake to think that we could grow more prosperous on the back of more tourism. This is because each additional job in this sector, as it’s currently configured, drags the overall average down. If we target only high-value tourism jobs, as is often proposed, there are by definition likely to be significantly fewer jobs and so it would have less impact on overall numbers.

Secondly, we need to be careful before we dump too hard on the rural sector in general and dairy specifically. As he said:

If it weren’t for Fonterra we’d be desperately poor.

This point in particular is often missed by people who want to encourage growth in the “tech” sector. He didn’t suggest we needed to replace jobs in tourism or agriculture with technology jobs, but that we need to create new businesses in addition to those existing sectors.

Between 2010 and 2020, revenue per FTE in New Zealand, as reported by the OECD, increased from $110,500 to $144,400 – only a 12% lift in real terms.13 In either case, that 2020 value is a good benchmark for each of us to consider when reflecting on our own payroll - are we dragging the average Every organisation can compare their own payroll to that benchmark and determine if they are dragging the average up or down.

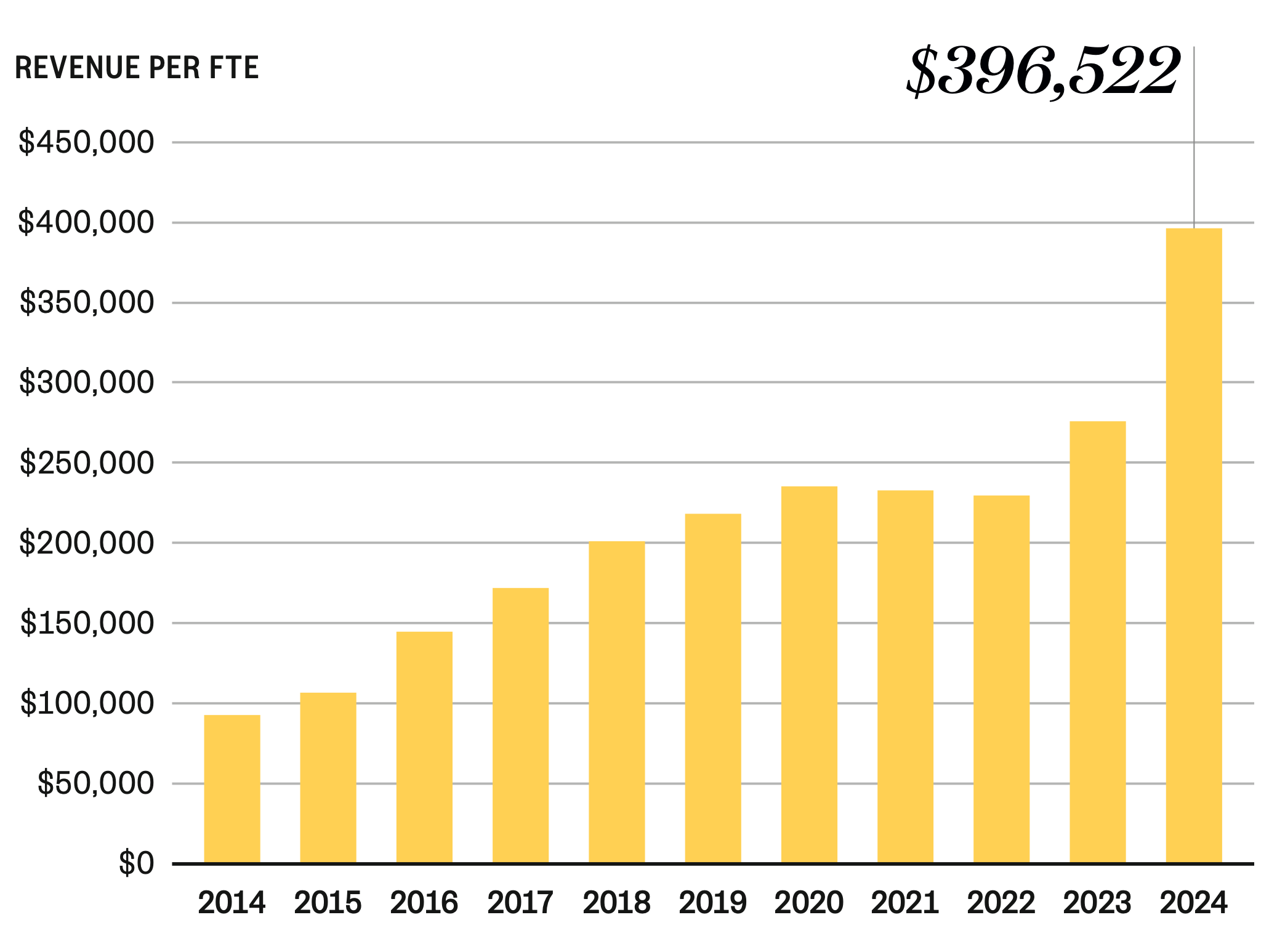

As an example, let’s consider this graph of revenue per FTE for Xero, which back in 2011 wasn’t on the radar at all but is now a good case study:

In 2024 Xero reported revenue of $396,500 per FTE. This value increased every year between 2007 and 2020, and has been improving the national average ever since 2015.

6. You can’t manufacture in New Zealand

Back in 2011 the most successful local “tech” companies were nearly all manufacturers: F&P Healthcare, Rakon, Tait Electronics, Gallagher. Even Callaghan’s own company, Magritek. So thinking about the contribution that manufacturing, and specifically what’s called “elaborately transformed manufacturing”, could make was logical. As Callaghan explained, the goal is to make products with high profit margins and high value per weight, which would require a significant investment in research and development (R&D). Not surprisingly this has been a big focus for Callaghan Innovation – the Crown entity set up in 2013 – and the government generally in the years since.14

In 2011, Callaghan said: “We own the sort of businesses that don’t need much R&D.” Unfortunately when we measure the total amount spent on R&D in New Zealand, it suggests this hasn’t changed:15

- In 2010: 1.25% of GDP vs OECD average of 2.24%.

- In 2022: 1.47% of GDP vs OECD average of 2.73%.

We’ve fallen further behind.

7. We are small so we need to specialise

The instinct to pick winners is seemingly timeless. As Callaghan explained, trying to anticipate the specific types of businesses that are likely to be successful is much more difficult than it seems on the surface. This is because building a successful business is not just about an innovative idea, it’s about execution. To return to the examples he used, while it might seem that New Zealand should have competitive advantages in biotech or cleantech, the large amounts invested in those areas from the top down have had little impact. Instead, he predicted:

We better be prepared to be good at some pretty weird stuff.

Where have the biggest successes since then actually come from? Callaghan highlighted the top 10 exporters from the 2010 Technology Investment Network Report (TIN).16 Together those companies generated $3.9 billion of revenue per year. The top three, F&P Appliances, Datacom and F&P Healthcare, accounted for nearly 60% of that amount.

His proposal was simple in theory: to generate the additional $45 billion needed to close the gap with Australia we needed 100 more companies of that size (actually 115 additional companies, for a total of 125 companies, but let’s not get distracted by detailed maths).

How much progress have we made towards this target? In their 2023 report TIN listed 17 companies that were at least as large as the 10th largest from 2010 on an inflation-adjusted basis. Seven companies remained above that threshold. Curiously, the 10th-placed company from 2010, Moffat, was not one of those, having dropped to $102 million revenue in 2023. Their 2010 result was marked in the report as an estimate, so possibly an overestimate? The other two companies from the 2010 top 10 who dropped out were NDA and Rakon with 2023 revenues of $186 million and $180 million respectively. Another six companies had moved up from further down the list in 2010, having grown revenues sufficiently, most notably Xero. There were four newbies, including the mobile payments app developer Pushpay, founded in 2011, Transaction Services Group, apparently founded around 2001,17 Rocket Lab, founded in 2006, and already with a successful orbital launch under their belts by 2010, and Livestock Improvement Corporation, founded in 190918 (it’s not clear to me why those latter three weren’t on the 2010 list).

That’s a net increase of just seven companies. Together those 17 companies contributed additional revenue of $6.39 billion. That means in 13 years they contributed less than 15% of Callaghan’s original target.

It gets worse. This trend is even more depressing if we consider that the very first TIN Report in 2005 contained 13 companies with reported revenue greater than $100 million. This increased to 17 companies by 2010 and to 34 companies by 2023. So even over that longer time period the growth of new companies in that bracket has been anaemic.

Reflecting on Callaghan’s conclusions, based on TIN data, I believe he got some important things wrong. First, software companies are prominent. When we think about manufacturing we’re dealing with exports that are higher volume by weight, and typically involve expensive R&D. Where do software companies fit in – with technology that is often low-tech, but with potential that has been proven multiple times now to generate a lot of weightless export revenue? Of course, this should be a “yes, and…” not a “yes, but…”

Secondly, the results further down the list have been much more impressive. In 2010 the 100th-biggest company listed was Triodent with revenues of $12 million. In 2023 the 100th-biggest company was Link Engine Management with more than twice the revenue ($26.9 million). In 2010 there were 51 companies listed with more than $30 million revenue. By 2023 that number had increased to 96 companies (an 88% increase). In 96th position in 2023, with revenue of $30.1 million, was Magritek, the magnetic resonance spectrometer company co-founded by Paul Callaghan. Further down the curve there are many founders, under the radar, who have created significant smaller businesses, each with their own teams. Often the first we hear of them are when those businesses are sold. Maybe, rather than a small number of very large companies, the “weird stuff” we are good at is going to produce a much larger number of smaller companies.

Towards the end of the 2011 talk Callaghan references the average size of the largest companies, and says:

I believe that just a hundred inspired entrepreneurs could turn this country around. It only takes one genius entrepreneur to make a company like this. So a hundred individuals could earn us $40 billion a year in exports.

To mimic Callaghan’s own myth-busting approach, this idea of a lone genius is a seductive but all-too-common misconception. We’re actually not a small country, but we are a very lightly populated country. Because we don’t have enough people with the skills we require to be competitive, people-lite solutions like this will always look attractive. It’s a typically Kiwi attitude to put innovators and inventors on a pedestal (and to talk about No 8 wire and claim to be punching above our weight). It’s tempting to believe that one person does it by themselves, just as we like to believe that New Zealand is clean and green or that to be more prosperous we’d just need to work harder.

But it takes much more than one crazy individual to create an enduring high-growth company. It’s true that there is often just a single name attached to each of the businesses that becomes big enough to get our attention. Trade Me is Sam Morgan, Xero is Rod Drury, Vend is Vaughan Rowsell, and so on. And this same small group of visible founders gets the bulk of the headlines. It doesn’t diminish those individuals’ formidable achievements to point out that as soon as we scratch the surface of any of these companies we find that they were built by a large team of people, with a wide range of skills and specialities, all working together.

Every founder who aspires to build a substantial business needs to hire hundreds of qualified specialists. We don’t only need 100 founders. We need 10,000 people contributing their expertise to these businesses. Then 100,000 more.

That’s the real constraint.

Callaghan correctly identified that skilled people would be the most significant thing stopping us from creating and sustaining the high-growth companies we need. To attract and retain them, he said, New Zealand would need to:

Be the place where talent wants to live.

This idea has been very popular ever since. Part of the reason, I suspect, is that many of us just assumed it was already true, so there was nothing more we needed to do. And yet, today our high-growth companies are desperately short of the people they need.

I wish he’d phrased it differently. First, people are not talent. People have talents. Secondly, it’s not enough to just have skilled people live here. We can’t just be the place where people who have already been successful come to retire or escape from the world. That doesn’t help us. We need people who are still hungry for success to work here. Finally, we never connect the dots between these skilled people and our collective prosperity. Successful companies can create a huge amount of value for the individuals who invest in them and work on them. But we never explain how that value flows also to everybody.

It doesn’t roll off the tongue so easily but a revised version might be:

Be the place where people who contribute more than they take choose to live and work.

However we phrase it, the inescapable question remains: Why will these people choose New Zealand? We need to understand and describe our competitive advantage. It needs to be much more specific than “100% Pure”.

The unimaginable future

Go back to the opening statement Callaghan made in his keynote:

We don’t think about the future terribly well in New Zealand.

The thing about the future is it’s happening constantly. The future he imagined years ago is what we now call the present. At the same time, these are the good old days we will look back on fondly in years to come.

In March 2012, just a few months after I saw him speak, Callaghan died of cancer, aged 64. The biggest mistake we can make today, when we consider his legacy, is to just repeat his mantras without understanding that if he were still here now his thinking would have developed and evolved, based on the results that have been achieved and the lessons learned in the process. I imagine he would be delighted but not surprised that the biggest successes so far were all somewhat unpredictable, even as recently as 2011. And he would warn us that future successes are likely to be just as unexpected.

How have we built on these ideas he shared? How should we update them for our current reality?

Sources

Data referenced here was correct as at September 2024.

I’m grateful for the following organisations for the data sources which help to shine a light on the questions I’m asking:

Notably, the only data set I’ve relied on which isn’t freely available is the TIN Report. The 2020 and 2023 editions of this report each cost me $450. For that I got a link and password to access a digital copy, which I couldn’t even download. NZTE and other government organisations have funded this report extensively over the years.

-

The recording is still available. It’s just over 20 minutes long and worth watching if you’re interested in this history:

Sustainable Economic Growth For New Zealand: An Optimistic Myth Busting Approach, YouTube.

There are parts of it that have aged quite significantly, but most of it feels just as relevant today.

By 2011 Callaghan updated the title of his talk to be much more direct in its aspiration:

New Zealand: The Place Where Talent Wants To Live, Vimeo. ↩︎

-

This analysis could be repeated using wealth as the measure rather than incomes. The OECD Gini Coefficient rankings are calculated excluding housing costs. ↩︎

-

Household income and housing-cost statistics: Year ended June 2020, Stats NZ, 16 February 2021. ↩︎

-

The truth about inequality in New Zealand by Andy Fyers, Stuff, 17 January 2017. ↩︎

-

Income inequality, OECD. ↩︎

-

It’s not easy seeming green, The Economist, 23 March 2010. ↩︎

-

100% Pure Fantasy? Living up to our brand by Matt Stewart, Stuff, 1 December 2012. ↩︎

-

Dairy statistics, LIC. ↩︎

-

This is partly a result of new countries being added and impacting the underlying average – for example, Chile, Estonia and Slovenia in 2010, Latvia in 2016 and Colombia in 2020. ↩︎

-

The difference between per capita income in New Zealand and Australia in 2010, using current OECD data, was ~32% (so a bit lower than Callaghan’s figure of 35%). The OECD average GDP per capita in 2010 was US$11,674 per capita, which suggests the gap back then was more like US$51 billion – significantly more than Callaghan’s estimate of US$35 billion. ↩︎

-

This gap is calculated using 2023 OECD data, but this time using the Local Currency, Current Prices measures. ↩︎

-

This is a simple calculation, using his numbers: GDP per capita = ~$40,000, population = 3.9 million, FTEs = 1.3 million, so each of those 1.3 million FTEs needs to earn ~$120,000 to get to a GDP per capita value of $40,000 across the whole population. ↩︎

-

Callaghan, Revisited Calculations, Google Spreadsheets. ↩︎

-

In January 2025, the government announced Callaghan Innovation would be terminated with its “most important functions” reassigned elsewhere. Time will tell whether this amounts to more than a reshuffling of the deck chairs. ↩︎

-

The top ten exporters from the 2010 TIN Report (revenues as reported):

- F&P Appliances ($1.1 billion)

- Datacom ($667 million)

- F&P Healthcare ($503 million)

- NDA ($200 million)

- Tait Electronics ($200 million)

- Temperzone ($163 million)

- Gallagher ($160 million)

- Douglas Pharmaceuticals ($145 million)

- Rakon ($144.5 million)

- Moffat ($140 million)

-

NZ’s Transaction Services sells majority stake in $1b deal, NZ Herald. ↩︎

-

Livestock Improvement Corporation, Wikipedia. ↩︎

Related Essays

Building An Ecosystem

How can we build an ecosystem of innovative technology startups in New Zealand?

Picking Winners

Imagine objectively selecting companies to receive government support, without the bureaucrats or consultants?

People, People, People

Ask the best startups what’s holding them back and they all point to the challenges of finding and keeping great people.