I’m back in New Zealand after a couple of crazy weeks in Nepal.

I realised this was no holiday when I got to the airport in Auckland and saw some of the stuff the rest of the guys in the group I was travelling with were taking - their check-in luggage overflowing with tools and equipment.

Everybody had a job - to install electrical systems, or air quality systems, or to lay vinyl floors etc. It took me a while to work out my role.

I initially thought that I would just help by being a grunt, but of course there is no shortage of volunteers for that job in the third world!

In fact, when one of the senior local guys spotted me trying to help out with unloading the truck of equipment at the factory he got quite grumpy, and I was promptly whisked off to have a guided tour of his onion patch (seriously - they were nice onions!)

I eventually worked out that the best way I could help was by soaking up some of the endless hospitality the locals were so keen to arrange for us all, and in the process leave the other guys some space to actually get on with their jobs.

So, I ended up being more tourist than anything else.

In the process I covered quite a bit of distance on rough roads and on foot and got to see some amazing parts of the country.

Outside of the busy-ness of the Kathmandu valley it’s a really beautiful place.

Unfortunately photos really don’t do it justice. The experience is multi-dimensional. Without the heat, and the bustle, and the noise, and the dust, and the smell, and the tooting, and the taste, and the looming mountains at a height where you only expect clouds, you miss just about everything that makes it interesting.

Just driving through town is exhausting - there is so much to take in and all of your senses are in overdrive. Your life flashes before your eyes so frequently - as your driver lurches out into the opposite lane, one hand on the steering wheel and one hand permanently on the horn, at a speed that is much faster than the designer of the tiny little car you’re sitting in would have dreamed possible, only to discover that heading in the other direction is a public bus packed so full that people have overflowed onto the roof, while all sorts of livestock block the side of the road - it starts to become mundane.

It’s also amazing how quickly you become accustomed to things not working.

Especially in the smaller towns the roads are in a permanent state of disrepair, with massive potholes only making them seem even more narrow than they are. Although they do create some good opportunities for the local kids who put up ad-hoc road blocks - provided they position themselves just past a rough section of road then traffic is already slowed enough to allow them to stop cars and extract a few rupees.

In Kathmandu there is so much traffic - cars, buses, bikes, cows, as well as people on foot - that during the day it’s a permanent jam. On more than one occasion we left our driver to it and got out and walked. There are traffic police at the main intersections - they blow their whistle and point and wave their arms, but they are really on a hiding to nothing.

Out on the highway we passed one gang of guys hauling up a bus which has come off the road and crashed into the river valley below killing 30 people onboard. I’m not sure how many of those were inside the vehicle and how many were on the roof.

Around town every driver seems to know the width of their car/bike to the nearest millimetre, and to people familiar with “only a fool breaks the two second rule” it seems astounding that there are not more prangs. Or, maybe not…I’m told that if you injure someone in an accident you need to pay all their treatment, but if you kill them it’s a flat rate of 5000 rupees (approx NZ $100), so anybody who causes an accident is incented to make the extra effort to ensure they are not left with an ongoing bill for care (in other words: if you do get run over watch out for the car that just hit you switching into reverse!).

Technology is a bit of a mixed bag. Just about everybody carries a mobile phone, and calls are ridiculously cheap - about 4 rupees (or 8c) per call. But, on the other hand I was blissfully without an internet connection for most of the trip. When I asked at one of the places we stayed if they had access I was told it would be available tomorrow. This turned out to be an optimistic estimate (perhaps tomorrow as in tomorrow never comes), as I later discovered they were still waiting for trenches to be dug and wires to be laid so they could get connected.

Despite having so much hydro potential, there is not enough electricity to go around, forcing the country into a system of “load sharing” where one region at a time is disconnected for an hour or two on a rotational basis. Apparently there is a schedule, but even so the locals still seem surprised when it happens. Everybody scrambles into action, torches are found, candles are lit and generators are fired up, and everything quickly gets back to normal (apart from the tourists stuck in their room with no idea what is happening).

Despite the impact this sort of stuff has on their lives, everybody is so tolerant.

At the check-in desk at the airport on the way out they have a professionally printed sign which reads “System Down”. When that gets put up the waiting queue quickly sorts itself out - the Europeans and Americans get seriously agitated with the delay, while the locals just stand patiently hoping that it will soon be fixed.

Just like everywhere else in the world, it’s the people who make the place special.

While I was there they were celebrating Tihar, which is the local equivalent of Diwali and marks the start of the new year (I’ve seen in 2065 already!). All of the main streets and buildings were lit up for the occasion. Because there were a few days with less traffic even the smog took a holiday, and there were some nice clear views over the Kathmandu valley.

Sanjeev, who is the adminstrator at the cancer hospital in Bhaktapur, devoted himself to looking after me throughout the trip. He invited me around to his house for the Bhai Tika ceremony on the final day of the festival. It ended up being the highlight of the trip. They live as an extended family - his grandmother is 77 and his son is 3. Their place is about an hour out of Kathmandu, along some roads that the average kiwi SUV driver would probably feel a bit anxious about. But, they made me feel very welcome, and were obviously keen to let me experience a bit of what their lives are like. They seemed a little nervous about how I would react to the food, but it was fine - although I was pleased to have a knife and fork to eat with as I’m not nearly as efficient eating rice with my fingers as they are.

Maybe one day I’ll have the chance to return the favour. Who knows what they would make of my place? They would no doubt find it just as foreign and odd.

What about Nepal generally?

As you travel around there is not much evidence of wealth. In fact they make a mockery of what we call poor.

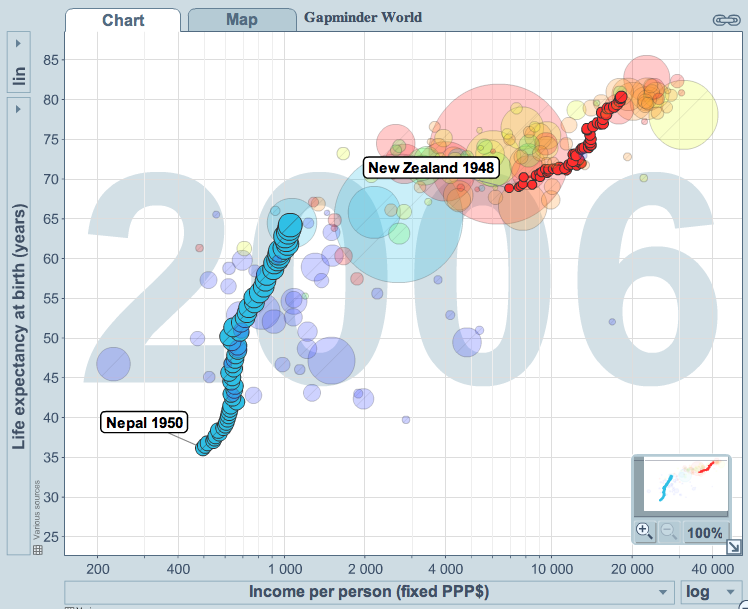

This graph from GapMinder shows the progress they have made since 1950:

Back then the average income was less than $500 per person, and the average life expectancy was only 36. The blue trail shows the change since then. The red trail shows NZ over the same time frame. For Nepal, both statistics have doubled in the last 60 years, but even so still they live shorter lives than New Zealanders did in 1948 and earn on average about 1/17th as much as we do now. Outside of Africa only Butan, Haiti and Timor-Leste are below them.

Overall I was left feeling pretty small and quite selfish.

It’s so easy to go on this sort of trip thinking that you are doing something good, but you soon realise that actually says more about you than anything. The amount of need is so overwhelming, that it’s very easy to feel completely hopeless. I certainly didn’t come away with a sense that anything I could do, or indeed anything that anybody could do, will make much of a dent. And I was depressed to meet a few locals who have started to become immune to people like me promising to help but following up with little, or nothing.

But, despite that, I did get to see a few examples of good stuff happening. Most, it seems, are where outside people with skills or resources that don’t exist there are supporting and pushing along the locals who are already trying to help themselves. This is obviously not a new model - Sir Ed did much the same thing, and even today a NZ $5 note is a popular present in Nepal.

Ray took me to Tilganga, which is a facility in Kathmandu that he was involved in setting up in the early 90s when he was working with the Fred Hollows Foundation. They manufacture world class lenses, which are sold around the world and provide a source of income to subsidise the cataract surgery and eye clinic that they run for the locals.

It’s not necessarily a free service as some of the patients who need treatment can afford to pay. So they have come up with a nice pragmatic system for determining how much to charge based on some simple things they can observe - for example, is the patient wearing shoes, do they have jewellery, have they come by themselves or with family members, etc. They still have a final subjective check, as some people will borrow clothes (and relatives!) from their neighbours for the occasion, but this at least makes the initial assessment objective, which is easier for the nurses who are reluctant to be making those sort of decisions.

When I was there there was a big crowd of people waiting patiently to be seen that day. Some, I suppose, left later that day with a much better life as a result.

It’s yet another example of an overnight success, which actually took 10 years.

Luckily there are some people willing to help who have that sort of patience required to see projects like that through. Most people, I suspect, are like me and would need a much faster pay-back.

If you’ve travelled to these sort of places yourself, then I doubt anything I’ve described here will be much of a revelation. If not, then I would strongly encourage you to, when you can. It will change the way you think, at least, and maybe the way you act too.

I reckon there is probably a bit of untapped demand for this sort of trip, where you can actually try and leave something a bit more substantial than footprints during your travels. That’s an idea that will bubble away in the back of my mind.

In the meantime, some photos :

Lots more on Flickr, if you’re interested.