This is the fairytale:

Our lone hero, an underestimated genius, slightly lacking in social skills, has an amazing idea for a new website or app. Locked in their bedroom, they hack away at a computer late into the night, powered by energy drinks. They launch the next morning, to great acclaim, and are immediately inundated with customers. They confidently power ahead, and within no time convince a slumbering corporate to buy their young company for squillions and promptly retire to a life blissfully sipping mojitos on the beach of a remote tropical island they’ve purchased with the proceeds.

It’s an intoxicating yarn. And there was a time when I pictured myself as the central character. But I’ve learned that in truth it’s fiction – a collection of myths. I count at least seven of them:

-

The myth of the Eureka! moment. Ideas are complicated. They rarely arrive fully formed. Many that seem great in hindsight started out as something entirely different. To curate our own ideas we need to balance gentleness with an unsentimental impatience. And we have to be honest about our results.

-

The myth of overnight success. It’s fun to imagine being inundated with customers immediately after we launch something new. That rarely happens. The reality tends to be grinding away for a long time without any attention, fighting to overcome obscurity. We have to focus on the things that build momentum, and try not to be distracted by all of the noise.

-

The myth of invention. Creating something genuinely new is hugely exciting. But turning that into a successful business is more about solving the sorts of problems that lots of people face. That requires empathy on top of technical skills. It’s not what the software does but what the user does with it that ultimately matters.

-

The myth of the lone genius. It’s common for a single person to be credited with creating a successful startup. But it always takes a team. Every famous founder needs to surround themselves with lots of other capable people who complement their skills.

-

The myth of “up and to the right”. Airbrushed startup stories can lead us to believe the reality will be a smooth ride, a straight line from start to end. As a result it’s even more of a shock when we experience the sudden plunges in our own ventures – and that’s why I was determined to start this book with those near- death experiences. How we cope when we get punched in the face determines our fate.

-

The myth of the accidental exit. Great businesses get bought not sold. The price that is paid nearly always reflects the value created for customers. When a successful startup is sold that creates a return for those who invested time and those who invested dollars. But starting out with that end in mind rarely gets us there.

-

The myth of mojito island. What happens after an exit? When we’ve poured ourselves into starting and growing a successful business is it possible to be happy doing nothing? Or do we constantly need to seek a bigger challenge? Not everyone will have the same answer to those questions. But I like to describe this welcome dilemma as “there is always a bigger boat”.

Right from the beginning, when I started to build a company, I quickly learned just how illusory they are.

Let’s start with three…

Eureka!

In 1999 I was living in Sydney and working as an IT consultant on a large Y2K project that was slowly driving me crazy. The dot-com bubble was fully inflated. I had a nagging fear I was missing out. As a software engineer, I was curious to experiment with the emerging web development tools. I started to get my hands dirty on evenings and weekends. But I had no idea what to build and, as a result, spent a long time going around in circles. My motivation wasn’t to start a company, it was to experiment with technology and learn what was possible. I was looking for the sweet spot between “challenging to build” and “achievable with constrained time and skills”. I didn’t really think about the potential business model at all. What interested me was the data model. The idea I eventually settled on came less from a moment of inspiration and much more as a consequence of frustration. I’ve subsequently learned that one of the few things that founders have in common is discontent.

My fiancée was living in Wellington, so I was a frequent flyer and very motivated to move back to New Zealand, if we could find somewhere to live. Back then classifieds were printed in newspapers, so finding a good flat meant getting up really early on a Wednesday or Saturday, and hitting the phones, as by lunch time all the good ones were taken. That was impossible for me in a different time zone. So I channelled my discontent and came up with the idea for what I’d eventually call Flathunt – a website where anyone with a flat or room to rent could advertise their properties, connecting with potential tenants or flatmates.

Even with the benefit of hindsight, it’s difficult to pinpoint a Eureka! moment. The website was built like a jigsaw, in small, seemingly insignificant steps, over the course of several months. One evening I worked out how to let people search and filter listings; one lunchtime I sketched out the user interface, which defined the scope of what I needed to build; waiting at Sydney airport on one trip home I was browsing unclaimed domain names and found that flathunt.co.nz was available; one weekend I found a local web host that supported databases – a “cloud” service provider, years ahead of their time, eliminating the need for me to purchase expensive server hardware.

When we make something new it’s a natural instinct to keep it secret and wait for the perfect opportunity to unveil our completed masterpiece. It’s tempting to continue to add more features. These days, as an investor, I recognise the pattern straight away. Inventors will ask me to sign non-disclosure agreements before they are prepared to tell me anything about what they are working on, whereas entrepreneurs will insist on talking, even when all they have is an idea. The better thing to do is to ask for considered feedback from anybody who will give an honest opinion. That is far from intuitive. It takes a lot of courage to tell others about our half-formed ideas, because chances are they won’t be anywhere near as excited about them as we are.

Thankfully I managed to avoid this pothole with Flathunt. Partly because I never considered what I was building to be especially original or technically interesting. But mostly because I had lots of questions and there were people I hoped might have some of the answers. Even all these years later I’m grateful to all of them, because with their help what I was building got better, little by little, and as it did my confidence and sense of urgency increased. Eventually that combination got me over the line.

I could look back and retrospectively invent a story about the mythical, magical moment when the idea popped into my head, perfect and fully formed. That would make a great story. It’s not what happened.

The firehose

It’s not enough to just have a good idea for a startup. To create value we have to execute that idea. Every founder needs to confront a fundamental question: how will you overcome obscurity?

While many founders worry about others stealing their ideas in the early stages, a much more urgent concern is confronting the reality that most people don’t care or (worse) don’t even know about us at all. Every day startups die of starvation, due to lack of customers. Very few ever die of drowning from a deluge of customers they can’t cope with.

Trade Me took more than four months to sign up 1,000 registered members, despite being completely free to use. Xero listed on the New Zealand Stock Exchange with only 100 paying customers, and those of us working there at the time accounted for a good portion of those. Vend had just six paying subscribers when I first invested in 2010. After 12 months of hard work that number inched over 200.

Looking back to Flathunt, I was utterly naive about how hard it would be to get anybody to give it a go. I tried everything I could think of with my limited budget. I printed out advertisements and pinned them to university noticeboards. Instead of including a phone number, the tear-off tabs had the website address. When I returned the following week, intending to replace them, it was sobering to discover most of the tabs untouched.

The website itself was still a work-in-progress. When somebody placed an advertisement it simply generated an email to me. I would manually enter the details into the database to create an illusion of automation. This is sometimes called Flintstoning (imagine the car from the old cartoon, powered by the feet of the passengers). It’s true that automation is critical to scale. But it’s also true that we can automate a process too soon – before we really understand the exceptions, how the process is used by customers and how to implement it efficiently. In any case, the number of emails I got was far from overwhelming.

I decided to be more proactive. I bought a newspaper every day, and called everybody who had advertised to ask if I could add their listing to Flathunt. I figured they would have nothing to lose, and some of them were willing. But the more interesting lesson was how many of the classifieds were placed by the same small number of property managers. One of them got quite annoyed when I called them for the third time in one morning. That helped me understand how the existing market worked, and led to my first important sale, to a real estate agent in Palmerston North, a couple of hours north of Wellington. I scrambled to build the “pro” listing features I’d promised as part of the deal.

Over the summer I hit the road and door-knocked every real estate agency and property manager I could find. Most were uninterested. I got a much better response at university campuses where there were more internet-literate people in need of a room or a flatmate who were also poor enough to flinch at shelling out $30 for a newspaper classified. They were willing to give this new thing a go.

I’ve seen this pattern many times since. In the beginning, the biggest category on Trade Me was computer parts. Later it was womenswear. There isn’t a lot of overlap in those categories, but if we’d tried to start with womenswear it wouldn’t have worked. Likewise for Xero, many of the early customers were independent contractors, who didn’t need the more complex accounting features that were still under construction, so were happy to use it even though the product was incomplete. The first customers can be very different from those who come later.

A few weeks after Flathunt launched I got some media coverage, when a friend introduced me to a journalist called Tom Pullar-Strecker. He published a short report in InfoTech Weekly, which included this slightly-cringy-in-hindsight quote from me:

There are a few other sites out there charging $1 a day to advertise. Even that small amount is enough to turn landlords and agents away. The internet works best when it’s free.

He asked me what my job title was. I thought it was an odd question as I was the whole company. I said “managing director”. After the article ran I got a phone call from an agent who asked to speak to the head of marketing. From the temporary office I’d set up in our dingy flat’s spare bedroom, I had to explain that was also me. That was an early lesson in the perils of pretending to be something you’re not.

I was desperate for listings. I had a chicken-and-egg problem: advertisers didn’t see value in listing on the site because there were no current listings; meanwhile anybody searching on the site didn’t find much there, so had no reason to come back.

But I knew it worked. Soon after I moved back to New Zealand, we found a flat for ourselves. It was listed at 2pm one afternoon, Emily spotted it on the site (by this point the listings were automated), we went and saw it at 4pm and signed the lease later that evening. We’d solved our own problem, at the expense of the number of listings on the site.

Two critical lessons from this time stand out. First, I learned that improving the website made little difference (despite significant room for improvement). The much bigger constraint was obscurity. Nobody knew it existed – and I wasn’t very good at sales or marketing. Growing the business wasn’t about making myself more efficient, it required skills I didn’t have and couldn’t afford to hire. It’s very tempting, especially for technical people like me, to focus too soon on optimisation. In practice it nearly always ends up being premature.

Years later, at Trade Me, we embraced a mantra borrowed from the New Zealand America’s Cup team to remind ourselves to focus on critical things:

Does it make the boat go faster?

I still think that’s great advice for companies that are growing, but before we can worry about that we need momentum. More relevant advice might be:1

You cannot steer a boat that’s not moving.

We only have to expand our operations once we have operations. Before we have customers there are definitely more important things to work on… like getting customers.

The second lesson was that people only tell their friends about things that are remarkable. Unless there is something genuinely different (or terrible!) about our idea it probably won’t be news, so we’ll need to find some other way to spread the word. At Trade Me we were fortunate to have an idea that was inherently viral. Once a new member sold some stuff that they assumed was worthless, they couldn’t help but tell everybody about it.

The idea that Trade Me didn’t spend any money on traditional marketing in the early days is also a myth. Very early on Sam purchased distressed billboard space at a heavy discount. The thick canvas billboards that sat folded in a corner of the office for years after were a good reminder that the sugar rush from that kind of marketing is typically short-lived. We were mostly lucky that we didn’t have much money at that time, or we might well have spent more of it on things like that. Being short of cash forced us to grow organically.

In building momentum, not all customers are created equal. Though it wasn’t entirely obvious at the outset, Xero’s early focus on accountants and bookkeepers eventually proved a potent way to spread the word and get in front of millions of potential small business customers.

At Vend we discovered that irreverent viral videos shared on YouTube were a great way to reach our target market of boutique retailers. We complemented that with Google AdWords, which back then were still relatively cheap, to generate in-bound sales leads, and worked hard to make the sales process as low-touch as we could.

Timely had to work harder for coverage and attention. One of the unique things about the business was the team was distributed and fully remote. In a lot of the early media coverage and commentary that was the hook. We took what we could get.

Before all of that, I discovered nothing about Flathunt was inherently viral. Nor was I blessed with a lucrative distribution channel. And in early 2000 Google AdWords hadn’t even been invented. I quickly realised that growing the business was going to require constant work and significant expense.

For all my ambition, the awkward truth is that Flathunt never really worked as a standalone business. After about three months I’d burned through our savings and needed to start paying my share of the bills. Flathunt was making enough to cover costs, but not enough to pay me a salary, so I started doing some part-time contracting work.

Around that time I had lunch with Sam Morgan and Phil McCaw. Sam was an old friend – we had been in the same class together at Rongotai College, but lost touch afterwards. Another mutual friend, David Randal, reconnected us when he realised we were both working on similar things. Sam had launched Trade Me about a year earlier, and had just raised $100,000 from some former colleagues who had recently set up their own business called AMR Consulting (the name composed by taking the first initial of Richard Abbott, Phil McCaw and Mark Richter – a fourth partner, Sharon Weaver, somehow managed to avoid the abbreviation). For that investment they got half the company. Phil explained that Trade Me needed a software developer and I was grateful for the opportunity. I agreed to work three days a week to start with. The bare-bones state of the home page when I joined highlighted that there was no shortage of things to do.

Soon after that they offered to acquire Flathunt provided I agreed to join the team as a full-time employee. I don’t think they had much interest in Flathunt. And “full-time” was a bit of an understatement.

Within the first year we completely redesigned the site, introduced usernames (rather than just showing everybody’s email address in listings), added photo uploading, and built autobidding. It’s hard to imagine today that Trade Me could have worked at all without those core features, but somehow it did. There were also a number of fruitless experiments – such as a Wireless Access Protocol version of the site for early smartphones that was likely only ever used by the team at Telecom who paid us to build it, and an SMS bidding system that was many years ahead of its time. With the benefit of hindsight those were distractions, but that wasn’t obvious then. The trick was recognising quickly and moving on. We learned to never get too attached to any particular idea. We learned how to be wrong.

I’d stumbled into a gold mine, even if it wasn’t obvious then. In seven years the $10,000 or so I’d invested in getting Flathunt started would return $30 million. Flathunt meanwhile continued to operate in the background. Years later it would be folded into Trade Me Property. What mattered to me at the time, however, was that I’d found something exciting to work on that had momentum, and a small team to work with which needed the skills I had. They were the good old days. I was all in.

Mojito island

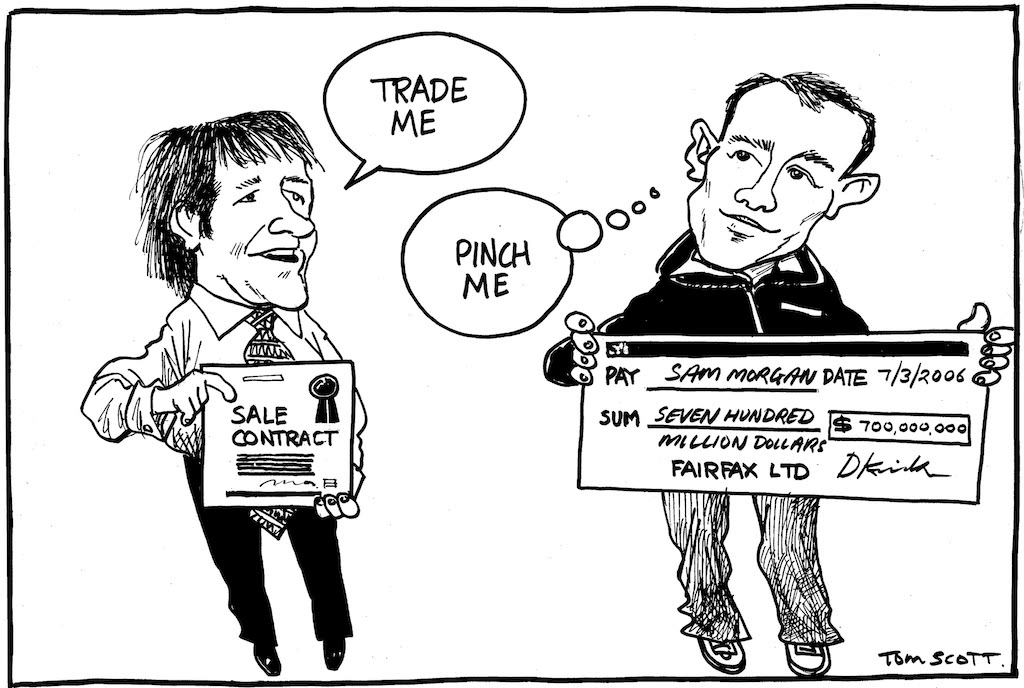

A flashy launch or a lucrative exit are news. But all the interesting steps come in between. Let’s fast forward to March 2006 when the small group of Trade Me shareholders gathered at the wood-panelled Buddle Findlay offices in the Wellington CBD on a bright Sunday morning to sign a pile of paperwork and finalise the sale of the business.

David Kirk, Fairfax CEO and former World Cup-winning All Blacks captain, was there on behalf of the buyer, the Australian public company Fairfax Media. The deal had taken several intense weeks to finalise, and everybody was anxious to close it out.

My main memory of that morning was the complications of arranging child care. Our 18 month old had been up all night vomiting. We had all been sworn to secrecy, so we were in the awkward position of having to call a baby sitter and ask them to come despite that, without being able to adequately explain why. “We’ll tell you tomorrow”, we said, “You’ll understand then!”

After the formalities were completed, we walked home through crowds of people doing their weekend shopping. I had a strange feeling, knowing what was likely to be the headline news story the next day. I had no clue how that would land with the general public, most of whom were Trade Me members by then, but more importantly with my teammates and family members. Was this an inflection point? And if so, up or down?

The next morning I went to the Intercontinental Hotel where Sam and David held a short press conference to announce the sale. I stood at the back with Mike O’Donnell (known as MOD), who was Head of Operations at Trade Me. I recall the reaction from many of the business journalists present when the price was announced. Bernard Hickey, who was working for Fairfax at the time, asked us to confirm that the decimal point was in the right place! He wasn’t the only one who thought that Sam had somehow tricked them into adding an extra zero to the price tag:

$750 million was (and is!) a staggering amount to pay for any business. But the real news that day was just how profitable Trade Me was. The price paid was a multiple of the earnings and reflected the high-growth trajectory we were on. It was no secret that we were growing quickly. But this was the first time that detail of the revenue that sat behind that growth was reported.

To attract the interest of an investor or acquirer for any venture the two basic motivating emotions to tap into are fear and greed. We need to have new and (often more importantly) growing revenue, or we need to be threatening existing revenue elsewhere. Trade Me had both. We had decimated the revenue media companies previously earned from classifieds. We joked that we were just working our way backwards through the sections of the newspaper – we’d done Classifieds, Motors and Property and were poised to launch Jobs then Travel at the time of the sale. And we had great margins. A large portion of every dollar we earned was profit. In the year before the sale, we made $26 million. In 2007 we nearly doubled that to $45.5 million. The following year we hit $70.1 million.2

In those days Trade Me was a fun and relaxed place to work. We didn’t wear expensive suits or take ourselves too seriously. The office was a bit chaotic and had graffiti on the walls. The pool table was a popular meeting room. But these were decoys. But we were 100% committed to the job. There were many people who confused our lack of formality for a lack of ambition. But it was a mistake to underestimate us. It was a place we all wanted to come to work. We put in the effort and achieved a lot.

After the press conference David came back to the office to meet the rest of the Trade Me team. He removed his suit jacket and tie, so he didn’t seem completely out of place. Compared to the thousands of employees in the other parts of his corporate empire I imagine it must have seemed like a small and young team. Within a few years the revenue that Trade Me contributed to the Fairfax group would become an important part of their business.

In 1998 (or “the late 1900s”, as my kids call it), long before starting my own company had entered my mind, I got some excellent career advice from a manager at Andersen Consulting. Unlike many of the other people on the team he had worked at a few different places beforehand, rather than coming up through the ranks at the firm. Perhaps that gave him a better perspective. It was obvious to him that I wasn’t enjoying the work I was doing. I’d started to think out loud about quitting. He took me aside and said:

I’m not going to try to convince you to stay, but don’t quit because you’re frustrated, leave because you’re excited about what you’re going to do next.

Thankfully, I took that advice and stayed on the project. I spent the next six months thinking about what I wanted to do instead. The decisions I made during that time have shaped the rest of my life. I’ve subsequently given similar advice to several founders trying to decide if they should sell their company. Often the question of an exit has come up only because they have lost their enthusiasm and they are feeling exhausted. More than once I’ve said:

Don’t sell the company because you’re tired. Sell because you’re excited about what you can do with the proceeds – at least more excited about that than what you’re currently doing with the team and product you have.

Did we make the right decision to sell? Was $750 million enough? It created so many opportunities for myself and others, I never stopped to think about that question at the time. I had the same feeling when Vend and Timely were acquired in quick succession in 2021. In all three cases, half the uninformed reckons I heard were “You sold too soon!” and the other half were “How is it possibly worth that much?”

Kiwi business people are sometimes criticised for a lack of ambition – selling out once they have enough to buy a bach, a boat and a BMW. That’s misguided. Of course we should all aim higher than that, but I don’t think this means aspiring to own a private jet or super yacht instead.

After one of the shareholder meetings during the sale process some people were speculating about the impacts of this kind of lump- sum wealth. Rod Drury joined the Trade Me board in November 2005, a few months before the sale. AfterMail, the business he co-founded prior to Xero, had recently been acquired for US$14.7 million.3 I recall Phil asking him: “How do you spend that kind of money without everybody thinking you’re a rich prick?” Rod’s reply was perfect, if not especially helpful: “I’ve always bought expensive toys even before I could afford them, so people probably already thought that!”

As long as we measure ourselves based on how many things we own, we’re never going to be satisfied. There is always another level above – a more expensive car, a bigger house, a longer race.4 As soon as we achieve that, we quickly normalise it and start to take it for granted. There is nothing so amazing that we can’t get used to it. Then we start to compare ourselves to people who are slightly ahead of us. Our appetite is always slightly bigger than our stomach.

Consider this formula: 5

Happiness = Wanting What You Have / Having What You Want

How much time should we spend on each part of that equation? Anybody who understands how fractions work realise that the important thing to focus on is increasing the numerator (the wanting) not the denominator (the having).

Until we experience it, it’s difficult to describe how much better it is to work on something we’re invested in. It’s not two or three times better, it’s more like 100- or 1,000-fold. I’ve never seen anybody retire happy after working on a successful startup. They all say: “What can we do next? What’s the next level?” After the excitement of a startup that has momentum, and the rewards that come from that, spectating from the sidelines can feel like a step backwards. Even the biggest boat you can buy won’t compensate.6

We have to understand why we’re doing it all in the first place. Financial rewards are a way to keep score, but we need to be careful we don’t get too hung up on them, because even if we do everything right, it still may not work out the way we hope.

The only good reason to sell is when we’re more excited about what we’re going to do instead.

I didn’t realise it at the time, but I had a lot of unfinished business.

-

Mike Carden, Twitter, May 2010. ↩︎

-

Fairfax Media Reports Net Profit Of $386 Million, Scoop, 21st August 2008. ↩︎

-

Quest Software Acquires Aftermail, Quest Software, 5 January, 2006 ↩︎

-

For example, the Ultra Ironman. ↩︎

-

Measuring what makes life worthwhile, by Chip Conley, TED Talk, 2010. ↩︎

-

Mojito island is a mirage, by David Heinemeier Hansson, 37 Signals Blog, 21st September 2009. ↩︎

Related Essays

The Mythical Startup

Can we update the fairytale version of how a technology startup becomes a success?

LOAD * ,8 ,1

Stay curious about how things work, and how you can use them to make things of your own.

How to Scale

What a founder in one of the poorest areas in Kenya taught me about how to start and how to scale