What matters for most people is not how much they know, but how realistically they define what they don’t know.

It’s great to start something new with good intentions and high hopes. Eventually we need to ask the question: Is it actually working?

It is often difficult to know. There are four layers to understand:

- Inputs - the things we start with.

- Activities - the things we do.

- Outputs - the immediate results.

- Outcomes - the longer term impact or lasting change.

The temptation is always to reach for the latter option: don’t just measure inputs measure outputs; don’t just measure outputs measure outcomes; don’t just measure outcomes measure sustained outcomes or system changes etc.

However, there are two big problems with doing this:

It’s tough to separate the signal from the noise. Because there are so many other factors that can influence those results over time, it’s hard to isolate the things we do from the results we get. We need to show both that something happened, and that it happened because of the things we did. Even if we can point to outcomes, it’s still an incomplete answer. At best it shows a correlation. We need to attribute results. Otherwise we risk confusing activity for progress. Real impact is the difference between what happened and what would have happened anyway, without us.1

Also, even more importantly, we have to wait much longer before we get any answer. Sometimes it can be years before outcomes are obvious or even visible. In the meantime there is nothing to give anybody confidence that things are on track and that we’re building momentum. It’s tempting to just say “it’s too soon to tell” but without the feedback loop that’s created by scrutiny and consequences we are unlikely to meet our expectations.2

For something that has been done before, it’s absolutely correct to ask about the outcomes rather than just measuring inputs or activity. But when we’re measuring something brand new and (as yet) unproven, that doesn’t work. There is too much uncertainty.

Throwing vs. Catching

Seth Godin has a wonderful metaphor that explains this: 3

When we learn to juggle it’s easy to assume that the important skill is catching.

But actually the key is throwing.

This isn’t intuitive. But if we can learn to accurately launch the balls (or flaming torches, bowling pins or chickens) we are juggling so that they land where we can catch them effortlessly - e.g. without needing us to lunge and without distracting our attention - then catching takes care of itself.

We can use this same idea to improve how we keep score, report on our progress and measure our impact, even when we’re dealing with significant uncertainty.

We just need to clearly identify the important activity that we believe will lead to the outcomes we want over time, if we do a good job. And then, expand on exactly what we mean by “do a good job” - e.g. our equivalent of “throwing so that the ball lands where we can catch it easily”. That gives us something specific to start measuring immediately.

Taking this approach forces us to articulate up front what we think is hard and what “good” means; it creates a much shorter and easily measured feedback loop, so we can track our progress and improvement on a scale over time (which is much better than a binary success/fail measure); it eliminates more external variables; and it explicitly acknowledges the leap of faith we’re taking.

Of course, there is always a risk that we choose the wrong thing. But at least this way we have something concrete to be wrong about. As long as we acknowledge that when it happens, we can learn from being wrong and try to be less wrong next time.

Don’t ask, don’t tell

In many ways a startup is the worst possible combination of circumstances. We’re working on something that is extremely uncertain. The consequences of being wrong are daunting. And despite all that, we feel constant pressure to persuade potential investors and colleagues that we’re confident about the destination and the route we’re taking.

It’s a fast track to madness. A natural coping response is to over-invest in trying to be certain, free of doubts, unequivocally right. We rush to data that proves what we assume to be true and ignore anything to the contrary. We try to “fake it till we make it”. I’ve been guilty of doing all of these things. While I encourage others to avoid them, for some the only way to learn is by painful experience.

The biggest lesson I took from Trade Me and Xero is that trying to be right all the time is a mirage. Being ultimately right and achieving our ambitions involves being repeatedly wrong en route. The survivors are those who find a way to live in that state. If we map this out, there are three key behaviours which stop us.

Omission

The first (and most common) behaviour is to simply avoid ever asking the question – the grown-up equivalent of a toddler hiding behind their hands in a game of hide-and-seek. But when we refuse to consider the possibility that we’re wrong then we make it much harder to be right.

Despite what we try to project externally, unless we take the time to explore and understand the cause and effect, we really don’t have conviction. That might sound simple but it’s a serious challenge. The world is never static, so it’s hard work to isolate the impact of any specific activity – from a miracle drug to a simple marketing campaign. The scientific gold standard is a “double blind” study where people are randomly split into two groups. One group receives the intervention, the others don’t, and none of the participants or testers know who’s in which group until after the experiment is over.

Of course, it’s rare that we can be so clean and rigorous in our own testing, especially in a startup. But there are many other approaches. We can do a “single blind” test – where people don’t know which group they are in but we do. Or we can just watch – it’s amazing how much we can learn by simply observing what people actually do compared to what they say they would (stated preferences versus revealed preferences). It may be as simple as using one of the many available tools to display different versions of our website to a random proportion of our audience and observing how they behave.

Another form of omission to watch out for is group think – that is, when everybody assumes that somebody else is doing the work to test the connection, but actually nobody has.

Error

Even if we are committed to measurement, there are countless opportunities to introduce errors as we attempt to make it easier, cheaper or faster.4

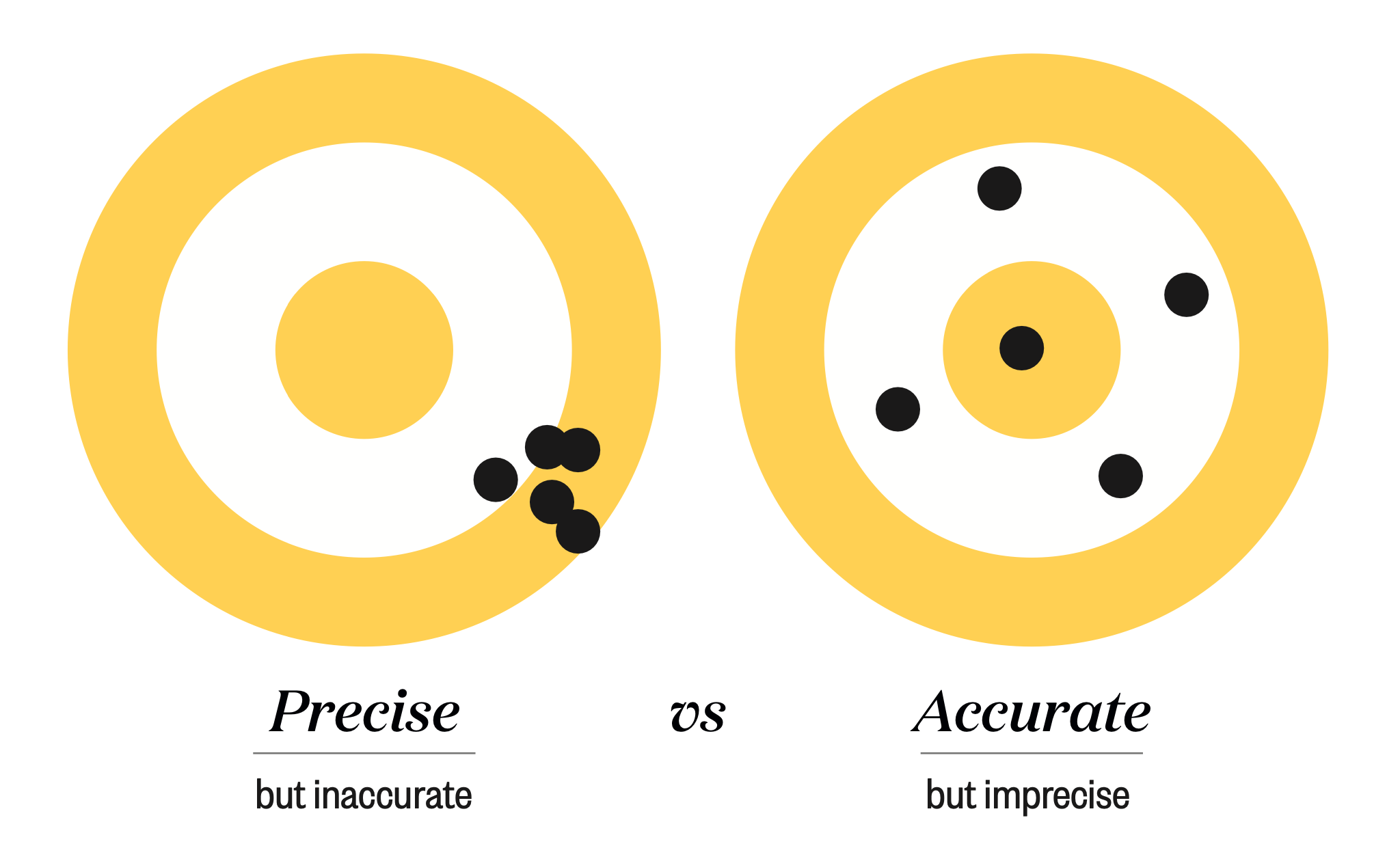

Researchers make the distinction between accuracy (how close the measured value is to the actual value) and precision (how similar multiple measurements of the same thing are to each other).5 Imagine throwing darts at a board aiming to hit the bullseye: the accuracy of our throwing is measured by how close to the bullseye each dart lands, while the precision is measured by how closely grouped our darts are. If we aim five darts at the bullseye and they all hit double-19, we would say our throwing is precise but inaccurate, as in the left target:

When our measurement is inaccurate, we end up with a systematic error – every result is incorrect in pretty much the same way. For example, early adopters are often not reliable indicators of how a larger general audience might respond. We can’t always rely on their enthusiasm to make broader decisions.

When our measurement is imprecise, we’ll get a random error – that lack of precision means our results are variable and our tests are not repeatable. When we extrapolate from a small customer base to draw conclusions, for example, just one or two outliers can skew our results.

There’s a third category of error, too: human error. We should never overlook the possibility that we simply messed up the calculation and so came to the wrong conclusion.

It’s always better to use facts than reckons to inform our decisions. But we also need to maintain a healthy scepticism about the reliability of our facts, keeping an eye out for any repeated bias that could mean we miss the important information in our data, and look out for results that indicate we’re mistaken.

Deceit

The final (and most destructive) behaviour is to just be dishonest. It might seem like this is the easiest one to avoid and so would be rare. But, as I’ve described, it happens a lot, inside startups especially. The underlying and unspoken motive often comes down to personal interest and self-preservation, reputation, and sheer fear.

Measuring results can be confronting – sometimes the evidence sends us the soul-destroying message that our assumptions have been wrong. While it might be tempting to lie when that happens, believe me, that seldom works out well.

How to be right

The good news is that by understanding how to be wrong, we significantly increase our chances of being right. Trade Me and Xero taught me that there are relatively easy ways to avoid all three of these behaviours. We can make sure we always ask the question, even if it’s uncomfortable. We can start with an assumption that what we’re doing isn’t working, then challenge ourselves to prove otherwise. We can switch from thinking in absolutes to thinking about how confident we are in our assumptions. For example, rather than saying, “I believe…” say, “I’ve realised…” and share the measurements that led to that realisation.6

This forces us to think about any corners we’re cutting in our testing and how that might impact results. It helps us identify the important metrics. Most importantly, we can be humble and honest about the results. This is either very easy or very hard, depending on our character. I found it helped to discuss this in advance with people who don’t have such a vested interest in the outcome, so they can help to make hard decisions when required.

It’s counterintuitive, but the key to being right eventually is being more open to being wrong – and recognising it when it happens. We should ask: what did we learn and how can we apply those lessons to what we do next?

Success is throwing ourselves at failure and missing.7

-

Real World Impact Measurement, Kevin Starr & Laura Hattendorf, Stanford Social Innovation Review, 2012. ↩︎

-

See Ceri Evans’ definitions of these terms from Perform Under Pressure:

- Expectations - what standard have we set ourselves?

- Scrutiny - how are we going to know if we have achieved those standards?

- Consequences - what happens if we do/don’t achieve those standards?

-

The Game of Life, The Value of Hacks, and Overcoming Anxiety, Seth Godin on Tim Ferriss Podcast, Episode 476, 29th October 2020. ↩︎

-

Experimental Errors and Uncertainty, G A Carlson. ↩︎

-

Alternatively called “validity” and “reliability”. ↩︎

-

See Thinking in bets by Annie Duke. ↩︎

-

I dont’t know the original source of this quote, but I attribute it to Richard Taylor, the co-founder of Wētā Workshop, best known for his work on The Lord of the Rings trilogy for which he won four Academy Awards. He was likely paraphrasing Douglas Adams, who wrote in Life, the Universe, and Everything: “The Guide says there is an art to flying […] or rather a knack. The knack lies in learning how to throw yourself at the ground and miss”. ↩︎

Related Essays

How to Scale

What a founder in one of the poorest areas in Kenya taught me about how to start and how to scale

Leap of Faith

Don’t confuse risk with uncertainty - be clear about what we know is true and what we hope might be true.

Discomfort

How can understanding our relationship with pain help us conquer challenges?

Most People

To be considered successful we just have to do those things that most people don’t.