It’s important that we don’t confuse risk with uncertainty. When we already know how to do something, but don’t know if we can or will, that’s a risk. If we don’t know yet whether that thing is even possible, that’s uncertainty. We need to be clear about what we already know is true and what we hope might be true but haven’t demonstrated yet.

Similarly, it’s important to distinguish evidence from experiments. We use evidence to identify problems. We use experiments to solve problems.

These two things require surprisingly different mindsets. This is why when someone tells us something is broken, they’re usually right. But when someone tells us how they propose to fix it, when there is no proven solution, they’re often wrong. This is why simply describing an opportunity or raising awareness about a problem achieves nothing unless it convinces somebody to act. Potential must be fulfilled before it counts. Potential isn’t an end in itself.1 This is why, more often than not, the people who invent new things and the people who work out what those things are for and how to commercialise them are different people.

It’s easy to say we are led by data, and that we do what data tells us to do. But it’s never as simple as that. Data can sometimes answer our questions, but we need to ask them first. Managing without metrics is like flying blind. But trying to manage entirely by metrics is misguided. The most important decisions we need to make will often involve subjective judgement. In those moments we should use all the data we can get our hands on to inform our decision. But let’s not pretend that the numbers themselves will ever make those decisions for us.

Due diligence

Uncertainty is a defining characteristic of startups, and because of that a lot of the traditional investment patterns just don’t apply. I’ve seen this confuse a lot of well-meaning startup investors. For example, I’ve found they often spend a huge amount of time and effort trying to understand the risks involved. This work is commonly called “due diligence”. I’m not sure it is as instructive as they imagine it to be. We mitigate risks by understanding them in advance and planning how to avoid them. But mitigating uncertainty requires understanding what we’ll do if we’re wrong and by asking: what is Plan B? It’s tempting to believe that by being thorough we can eliminate risks in advance of making an investment. That’s a fantasy. There are always questions that we’re not able to answer. There are always things that are just uncertain.

I’ve found it much more useful to work together with founders and be explicit about the leap of faith. In other words, try to articulate exactly what we believe is possible, but cannot prove yet. Describing this uncertainty forces us to be honest about what we know and what we don’t know; to choose the specific experiments we will need to complete in order to close that gap as soon as possible; and to think in advance about what we’ll do when we’re wrong.

Everybody involved in a startup can use this technique. Founders shouldn’t wait for investors to do this work. That just invites an endless list of questions. Instead, just describe the leap we’re asking investors to make. This is a great way to separate those investors who believe that we can do it from those who don’t and so are likely to waste a lot of our time while they try to prove it in advance. Very few founders ever do this because they assume that investors want them to pretend they are certain. It’s reasonable for investors to ask about known risks and mitigations. But it’s more important to focus on the specific experiments the investment will fund, and decide if we believe those will be successful. Embrace the uncertainty rather than pretend that we can avoid it. I’ve found that great founders are delighted to work with investors who behave this way.

Be general and specific

When we explain our vision for the future, we should ask whether what we are describing is thematic or specific. A thematic vision is a top-down way of thinking and describes general trends. A specific vision is a bottom-up way of thinking and describes individual ventures or projects.

A thematic vision without a specific venture is academic. A venture without a supporting theme is likely to face headwinds. The best ideas combine the two: a specific venture created to capitalise on a general trend. For Trade Me the general trend was the web as a consumer platform. The specific idea was to replace the newspaper classifieds by taking advantage of the benefits of the web (such as longer descriptions, photos and breadth of access) and to create a network effect, in which a growing user base makes the service itself more appealing. For Xero the general trend was the shift to software applications delivered via the internet and billed on subscription – known as software-as-a-service or SaaS. The specific idea was accounting software for small businesses, using accountants and advisors as the sales channel.

Successful investors look for the intersection of the general and the specific.

Taking the first step

All investment is speculation. The only difference is that some people admit it and some don’t.

As investors we’re likely to still feel tentative, even after we’ve identified the leap of faith that is required and described our vision for the future. That’s completely normal. We need to ask: what are we waiting for? Or put another way: what do we need to know is true before we would be ready to fully commit (or decline)? Sometimes, when we make that list we discover that those things are already true, in which case we’re just procrastinating for no good reason. Other times, it highlights that the questions we’re asking won’t be answered until much later. Rather than wasting energy on those, we can instead get moving with smaller experiments that can help resolve some of that uncertainty.

Making sure that everybody involved in a new venture understands the leap of faith in advance continues to pay dividends even after the investment is made. The question to constantly test is: do we still believe?

If the answer is “yes”, then what’s the next thing we need to do to get closer to knowing?

If the answer is “no”, then it’s time to stop and make different plans.

Related Essays

Unit of Progress

Be specific: Where are we going and what will it take to get there?

Feedback Loops

How can we be more explicit about the sort of feedback that is useful, right now.

Show Me the Money

Trying to decide how to fund a startup? It’s important that we ask the right questions.

How to Pitch

We realised that the most effective investment pitches all start with the same two words…

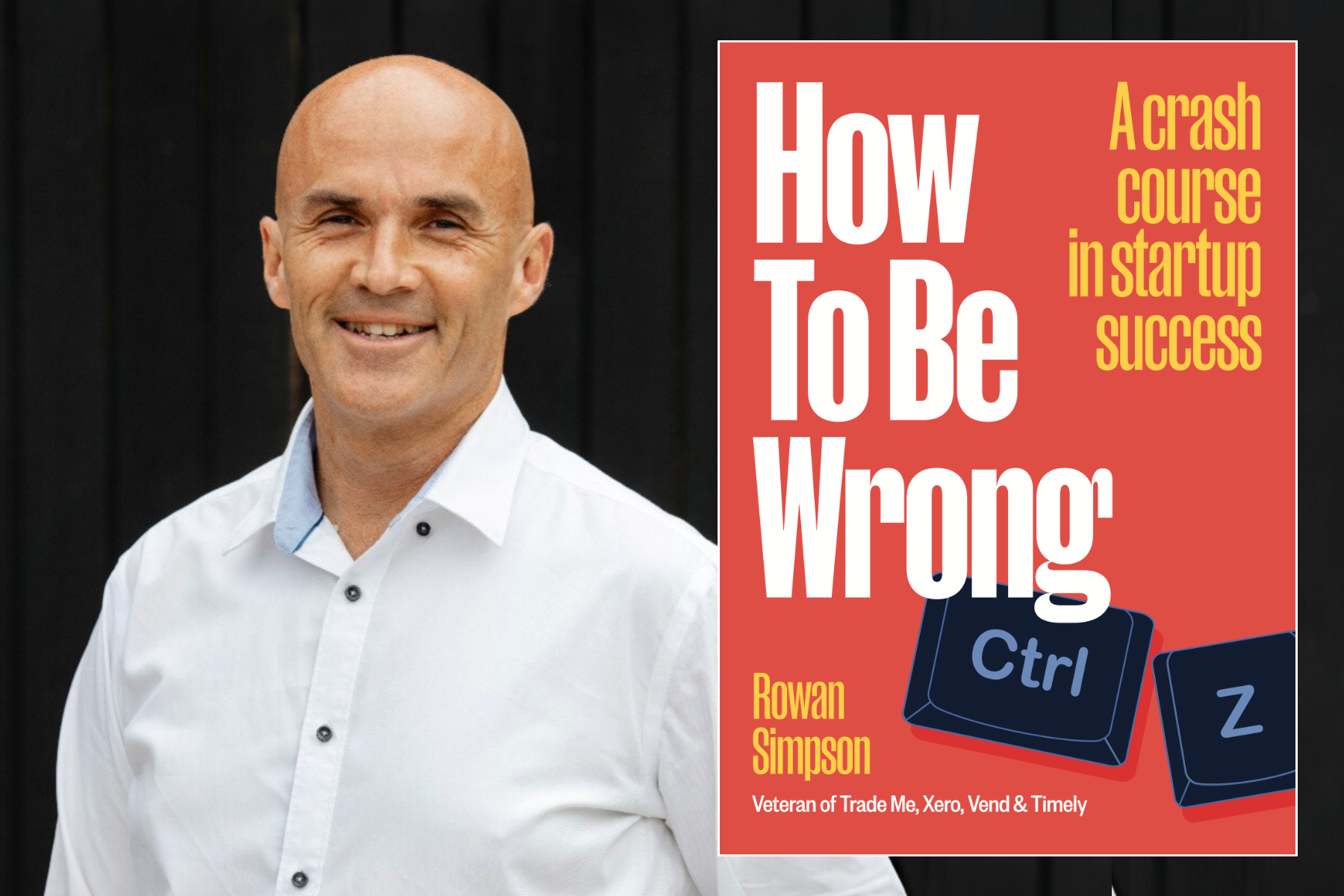

Buy the book