The most effective investment pitches all start with the same two words.

Most product-centric founders start their pitch by demonstrating a solution. They describe what they’ve built or hope to build, particularly when the solutions involves genuine innovation or invention.

Sales people usually start by describing the problem, and their vision for how that problem might be solved.

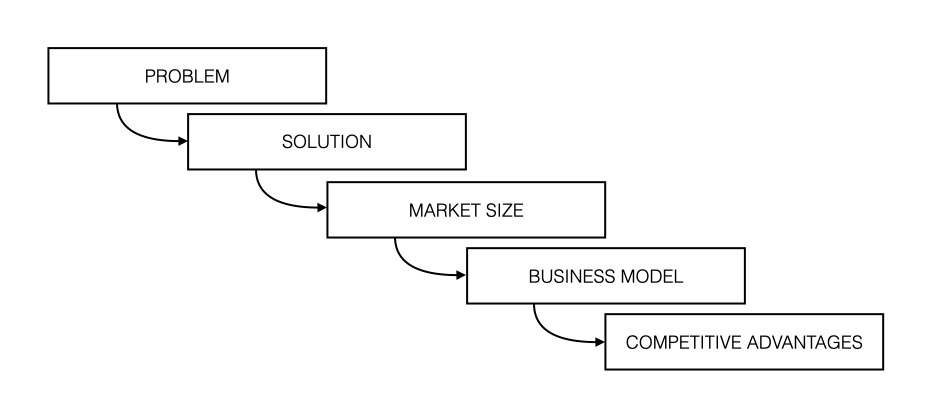

This approach became popular some years ago after the original Airbnb pitch deck was shared.1 This simple format they popularised was widely adopted:

Finance people typically start their pitch with numbers.

When we have metrics that demonstrate momentum and market validation then it’s tempting to just share those and let potential investors extrapolate. The great thing about results, even if they are very early or building on a small base, is that they stick in the mind of the person receiving the pitch much more effectively than promises. But facts can also easily ruin a great story, so we need to make sure all of the numbers are good, or at least be prepared to explain those that are not.

However, after hearing a lot of them, I’ve realised the most compelling pitches take a very different approach:

Start with the insights gained from the experiments completed so far.

The most valuable insights combine a lesson learned from experience with a proposed next step. They are small actionable units of truth.2 So, try to start a pitch with these two words: we realised…

Leading with insights allows us to explain how our understanding of the problem and the solution we are working on have evolved over time, and can continue to improve, rather than requiring us to pretend that we already have the answers. It avoids the common deceit of needing to present a solid and unchanging vision for the future (remember what Yoda said: the future is always in motion). It’s also a great way to demonstrate our competitive advantage - it’s hard to catch another team who are learning faster.

To solve any problem we need to experiment. If we haven’t completed any experiments yet, and so don’t have any useful insights to share yet, that’s a sign that we’re probably not ready to pitch for investment.

Here is a simple pitch deck template you can use, if you want to try this approach: 3

Key Insight

- “We realised …”

Product Statement

- “We are… [description of product/service] for [target customer]”

Use a large font and as few words as possible. Avoid the temptation to fall into a full product demo.

One technique to find these words is: Ask somebody to describe the idea to a third person. Then listen carefully to the words they use and steal those. This will literally use a different part of your brain.4

Remember, if we’re hoping to grow via word-of-mouth this is exactly how the idea will spread!

Who wants this?

- Customer pitch (i.e. the key benefit + compelling reason to buy)

- Price and business model

- Competition, if relevant (i.e. what customers currently use instead)

It’s most common to describe the competition using a quadrant diagram. This is rarely useful because we can always choose two dimensions which are flattering. So extract the key ideas from this and describe succinctly why customers are currently choosing the competing products and why we believe they will switch their preferences.

A useful format for this is:

Unlike [primary competitor] our product [description of key differences]

Why us?

- Team bios / skills / relevant experience

- Founding story (ideally this expands on the “We realised…” above)

Where are we now?

- Current metrics / traction

- Product evolution to date

- Customer validation

It’s common to include customer quotes in a pitch, but I’ve never seen one that wasn’t positive, so these tend to be ignored. It’s better to tell the story with numbers rather than words - i.e. tell us what people do vs. what they say they will do.

Where are we going?

- “We believe …” (see Leap of Faith)

- How will we get there?

- Specifically: How will we overcome our obscurity? What is the sales process? How repeatable is it? What does it cost to get a new customer? Are there network effects? What about the idea is, literally, remarkable?

Use a summary slide + extra slides to expand on each point.

What we need?

- “We are seeking … $X”

- Where does this get us? (see Unit of Progress)

- Financial forecast (3 years max, mostly focussed on expenses!)

- Investment history (if this isn’t the first funding)

Be careful to only estimate as far ahead as we reasonably can, given the stage we are at. It’s tempting to pretend this is further than it actually is.

Include revenue and expense forecasts that cover the same time period as the unit of progress.

-

Writing a business plan, Sequoia Capital. ↩︎

-

Kunal Shah: Core Human Motivations, Knowledge Project Podcast, Episode 141. ↩︎

-

I call this the “Melodics Format”, because the first time we encountered the important aspects of it was in the initial pitch we got from Sam Gribben, who is the founder at Melodics. ↩︎

-

Watching With Intent To Repeat Ignites Key Learning Area Of Brain, Science Daily, December 2006. ↩︎

Related Essays

Building An Ecosystem

How can we build an ecosystem of innovative technology startups in New Zealand?

Leap of Faith

Don’t confuse risk with uncertainty - be clear about what we know is true and what we hope might be true.

Unit of Progress

Be specific: Where are we going and what will it take to get there?