What matters for most people is not how much they know, but how realistically they define what they don’t know.

Measuring impact

To win we have to keep score.

My job title when I joined the team at Xero in 2007 was “Head of Product Strategy”. I assumed it was going to be up to me to work out what that meant. It didn’t take me long.

I remember one of the first product team meetings I was part of. The main item on the agenda was automated bank feeds.

Importing and reconciling transactions in accounting software is a tedious and repetitive process. After a lot of iteration the design team at Xero, lead by Philip Fielinger, had come up with a solution that made it fun, based on an assumption that bank transactions could be automatically imported every day. The first bank to provide this facility was ASB and as a result it was no surprise that many of Xero’s early adopters were ASB customers.

Around this time Rod and co-founder Hamish Edwards were working hard to find investors for the IPO. The pitch was that bank feeds were the killer feature that would convince small businesses to switch and stick. So, bank feeds were one of, if not the biggest, selling point.

As I talked about this with the team that day I naïvely asked the question: “How many existing customers are using bank feeds?” I was a little shocked to discover that nobody in the room knew the answer. I got the feeling it was a sacrilegious question to even ask!

At Trade Me we were used to measuring everything. Like any well used website, the Trade Me marketplace generates an insane amount of data. We worked hard to turn that into information we could use to make improvements. The beautiful thing about this was that most ideas could be quickly proved or disproved using numbers. Rather than letting ourselves get bogged down in long debates, facts trumped opinions.

It also created tight feedback loops. When we changed anything we could quickly see whether the impact was positive or negative. Over time that allowed us to develop a much better understanding of the product and our customers, and gave us confidence to make improvements, even when they might not be popular. When we got it wrong we would typically know straight away and could roll-back or adjust as needed.

A lot of that data was public. For example, we published details about the busiest day of the week and hour of the day, so sellers could use this to plan their listings, and the percentage of listings that sold for every category. Right from the early days, when the numbers were very small, we displayed a count of the number of members, the number of current listings and the number of people online at that exact moment. That transparency meant we never let a gap develop between what everybody assumed the numbers to be and what they were in reality.

It was a shock to land in a different team at Xero operating much more on faith. But it wasn’t difficult to understand why. We were dreaming big and telling a story of huge future potential. Eventually that would be realised, but back then there was almost nothing substantial to demonstrate that.

I realised then my job at Xero was to be gravity in an environment that required us to pretend we could fly.

I just kept asking the same two questions:

- Is it working?

- How do we know?

That didn’t always make me popular. For example, I didn’t win any friends by suggesting we focus on the number of paying subscribers we had (not many at that point) rather than on the number of business awards we could win (a growing shelf full of trophies at the office). But it did help to uncover some more of those situations where the answers were uncomfortable, and as a result we were able to make some improvements we needed to make.

In the case of bank feeds we immediately ran the numbers and discovered it was a very low percentage - only 19% of ASB accounts were connected to automated feeds. We quickly identified a number of experiments we could try to improve that percentage - from fixing the notifications that were displayed to customers who had set up a bank account but not connected to bank feeds, to phoning some of those customers who hadn’t and asking them why. I discovered when I did a few of these calls that people reacted very poorly to the idea that somebody at Xero could even see that was the case, which taught us some important lessons about privacy and data security too. Within a relatively short period of time we had nearly all ASB accounts connected and were able to use that to demonstrate to the other, slower, banks why it was important for them to offer the same facility.

Cutting to the core

It’s great to start something new with good intentions and high hopes. Eventually we need to ask the question:

Is it actually working?

It is often difficult to know.

There are four layers:

- Inputs - the things we start with.

- Activities - the things we do.

- Outputs - the immediate results.

- Outcomes - the longer term impact or lasting change.

Once we understand these layers, the temptation is always to reach for the latter option: don’t just measure inputs measure outputs; don’t just measure outputs measure outcomes; don’t just measure outcomes measure sustained outcomes or system changes etc.

However, there are two big problems with doing this:

It’s tough to separate the signal from the noise. Because there are so many other factors that can influence those results over time, it’s hard to isolate the things we do from the results we get. We need to show both that something happened, and that it happened because of the things we did. Even if we can point to outcomes, it’s still an incomplete answer. At best it shows a correlation. We need to attribute results. Otherwise we risk confusing activity for progress. Real impact is the difference between what happened and what would have happened anyway, without us.1

Also, even more importantly, we have to wait much longer before we get any answer. Sometimes it can be years before outcomes are obvious or even visible. In the meantime there is nothing to give anybody confidence that things are on track and that we’re building momentum. It’s tempting to just say “it’s too soon to tell” but without the feedback loop that’s created by scrutiny and consequences we are unlikely to meet our expectations.2

For something that has been done before, it’s absolutely correct to ask about the outcomes rather than just measuring inputs or activity. But when we’re measuring something brand new and (as yet) unproven, that doesn’t work. There is too much uncertainty.

Throwing vs. Catching

Seth Godin has a wonderful metaphor that explains this: 3

When we learn to juggle it’s easy to assume that the important skill is catching.

But actually the key is throwing.

This isn’t intuitive. But if we can learn to accurately launch the balls (or flaming torches, bowling pins or chickens) we are juggling so that they land where we can catch them effortlessly - e.g. without needing us to lunge and without distracting our attention - then catching takes care of itself.

We can use this same idea to improve how we keep score, report on our progress and measure our impact, even when we’re dealing with significant uncertainty.

We just need to clearly identify the important activity that we believe will lead to the outcomes we want over time, if we do a good job. And then, expand on exactly what we mean by “do a good job” - e.g. our equivalent of “throwing so that the ball lands where we can catch it easily”. That gives us something specific to start measuring immediately.

Taking this approach forces us to articulate up front what we think is hard and what “good” means; it creates a much shorter and easily measured feedback loop, so we can track our progress and improvement on a scale over time (which is much better than a binary success/fail measure); it eliminates more external variables; and it explicitly acknowledges the leap of faith we’re taking.

Of course, there is always a risk that we choose the wrong thing. But at least this way we have something concrete to be wrong about. As long as we acknowledge that when it happens, we can learn from being wrong and try to be less wrong next time.

Real impact is the difference between what happened with you and what would have happened without you.

Intentions → Impact

There are four questions that we need to answer in advance about any proposed solution: 4

- Who does this help?

- What constraints do they have?

- How do we hope to reduce or remove those constraints for them?

- How will we show that it’s working?

The first three questions insist that we’re much more specific about the who, what and how.

Rather than starting with the solution and trying to prove that it helps somebody, we should start with the specific customer we have in mind and the problems they actually have then work backwards from there to the answer.5

The fourth question gets to the specific things we can measure, what evidence we expect to have, and when we will know if something is or isn’t working. We have to answer these questions in advance. Otherwise it’s too easy to just shoot an arrow and draw the bullseye around whatever it hits.

These measures also need to include some early indicators and milestones. It’s not good enough to say that we will only know at the end. When something is working we can generally measure something right away that demonstrates momentum.

And finally, it’s useful to identify a “control” group as a comparison, so that we can attribute any results to the things we’ve done.

If we already know it’s going to work it’s not an experiment. Doing all these things forces us to be honest about the things we don’t know, which are also the things we might be wrong about.

When somebody asks “is it working?” it’s insufficient to just describe the things we’ve done, or the results so far. Instead, we should start by describing the people we’re trying to help and work backwards from there to show how the things we’re doing are actually helping them.

If we get this right we can get beyond working on things that just make us feel good and instead do things that really are good.

The three horsemen

It’s natural to over-invest in being right.

In many ways a startup is the worst possible combination of circumstances: we’re working on something that is extremely uncertain, the consequences of being wrong can be significant, and despite that we have to constantly convince potential investors and colleagues that we’re confident about the destination and the route we’re taking to get there. It’s a fast track to madness.

The unlock occurs when we realise there are only three ways to be wrong:

1. Neglect

The first (and most common) way to be wrong is to simply avoid ever asking the question.

We do some work and observe some changes happening, but how do we know that the things we do are the cause of the changes that we see? If we don’t take time to answer this we can’t say with any conviction that there is a connection.

Behaving this way is the grown-up equivalent of the toddler hiding behind their hands in a game of hide-and-seek.

The world is never static, so it can take a lot of effort to isolate the impact of a specific action.

Let’s say we want to know if something new works (it could be anything from a drug to a marketing campaign)…

The scientific gold standard is to do a “double blind” study. People are randomly split into two groups: some who receive the intervention, and others who don’t. Importantly nobody knows which group any individual is in until after the test is completed and the results are collected.

If we can show that one group had different results from the other we’ve proven a connection between the action we took and the impact it had. And if not, we’ve still potentially learned something useful.

Of course, it’s rare that we can be so clean and rigorous in our testing. There are still lots of other ways that we can observe results and collect data to establish this connection. We can do a “single blind” test - where people don’t know which group they are in but we do. Or even just watch - it’s amazing how much we can learn by observing what people actually do compared to what they say they would do.

Another common, but often overlooked, form of neglect is group think - that is, when there are enough people involved in an activity that everybody assumes that somebody else is doing the work to test the connection, but actually nobody has.

The easiest way to be wrong is just to not ask the question.

2. Error

The second way to be wrong is to make a mistake.

Measuring our results accurately is often difficult, expensive and time consuming. So there are almost infinite opportunities to introduce error, as we attempt to make it easier, cheaper or faster.6

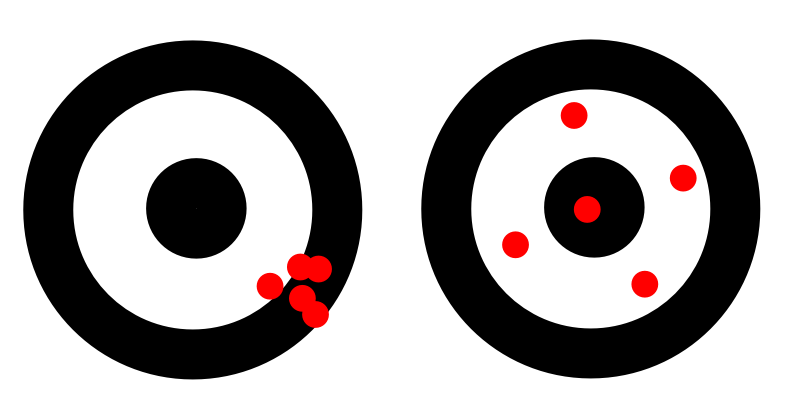

Researchers make the distinction between accuracy (the difference between the measured value and the actual value) and precision (how similar multiple measurements of the same thing are to each other).7

If we imagine throwing a bunch of darts at a dart board aiming to hit the bullseye, the accuracy of our throwing is measured by how close to the bullseye our darts are, while the precision is measured by how close to each other our darts are. If, for example, we throw five darts and they all hit double nineteen when we were aiming for the bullseye, we would say our throwing is precise but inaccurate.

There are different types of errors:

- Human error - we just messed up the calculation and as a result came to the wrong conclusion.

- Systematic error - there is a bias with our test that means every result is incorrect in the same way (i.e. our testing is not accurate).

- Random error - there is variability that means our tests are not repeatable (i.e. our testing is not precise).

So even when we are measuring our results, it’s still possible to be wrong when errors are introduced.

3. Malice

The final way to be wrong is just to be dishonest.

It might seem like this is the easiest one to avoid and so would be rare. But inside startups especially, it happens a lot. Often the underlying and unspoken motive for doing this comes down to personal interest and self-preservation: perhaps being honest would have a negative impact on our career or reputation; perhaps it would be politically expensive in our organisation or community; or perhaps too much has been invested already on the assumption that what we’re working on will have a positive impact for it to be comfortable for us to admit otherwise.

Either way, the con just requires us to know that there is no link between the things we do and the results we see. At that point we can either say nothing, and hope that nobody else notices, or (worse!) we can straight out lie and pretend that the opposite is true.

How to be right!

The good news is those are the only three ways we can be wrong, and there are relatively easy things we can do to avoid all of them.

We can make sure we always ask the question, even if it’s uncomfortable. It’s better to start with an assumption that what we’re doing isn’t working, then challenge ourselves to prove otherwise.

We can also switch from thinking in absolutes to thinking about how confident we are in our assumptions. Rather than saying “I know… " say “I’m x% sure that…” and base the x on actual measurements we’ve done. Doing this forces us to think about what corners we are cutting in our testing and how that might impact results.

Lastly, we need the discipline and humility to be honest about the results. This is either very easy or very hard, depending on our character. It helps to set up external checks in advance, so that others who don’t have such a vested interest in the specific outcome can be the final judge. It’s difficult to not take the outcomes personally if and when the testing shows that the actions we took didn’t generate the result we were hoping for. The more important question should be what did we learn and how can we apply those lessons to what we do next?

Remember, all we need to do to be right is to avoid being wrong.

Success is throwing ourselves at failure and missing.8

Easy!

-

Real World Impact Measurement, Kevin Starr & Laura Hattendorf, Stanford Social Innovation Review, 2012. ↩︎

-

See Ceri Evans’ definitions of these terms from Perform Under Pressure:

- Expectations - what standard have we set ourselves?

- Scrutiny - how are we going to know if we have achieved those standards?

- Consequences - what happens if we do/don’t achieve those standards?

-

The Game of Life, The Value of Hacks, and Overcoming Anxiety, Seth Godin on Tim Ferriss Podcast, Episode 476, 29th October 2020. ↩︎

-

These questions are inspired by Laura Hattendorf & Kevin Starr from the Mulago Foundation.

They have thought deeply about impact investment and how to identify and invest in the highest impact giving opportunities.

The “What we look for?” section of Mulago’s “How we fund?” website identifies three elements:

- A priority problem;

- A scalable solution; and

- An organisation that can deliver.

See also Kevin’s PopTech talk from 2011, which explains these ideas in the context of their philanthropic work. ↩︎

-

This is a Steve Jobs quote:

You’ve got to start with the customer experience and work backwards to the technology. You can’t start with the technology and try to figure out where you’re going to try and sell it.

Steve Jobs Insult Response, YouTube. ↩︎

-

Experimental Errors and Uncertainty, G A Carlson. ↩︎

-

Alternatively called “validity” and “reliability”. ↩︎

-

I dont’t know the original source of this quote, but I attribute it to Richard Taylor, the co-founder of Wētā Workshop, best known for his work on The Lord of the Rings trilogy for which he won four Academy Awards. He was likely paraphrasing Douglas Adams, who wrote in Life, the Universe, and Everything: “The Guide says there is an art to flying […] or rather a knack. The knack lies in learning how to throw yourself at the ground and miss”. ↩︎

Related Essays

How to Scale

What a founder in one of the poorest areas in Kenya taught me about how to start and how to scale

Leap of Faith

Don’t confuse risk with uncertainty - be clear about what we know is true and what we hope might be true.

Discomfort

How can understanding our relationship with pain help us conquer challenges?

Most People

To be considered successful we just have to do those things that most people don’t.