We can understand how we understand.

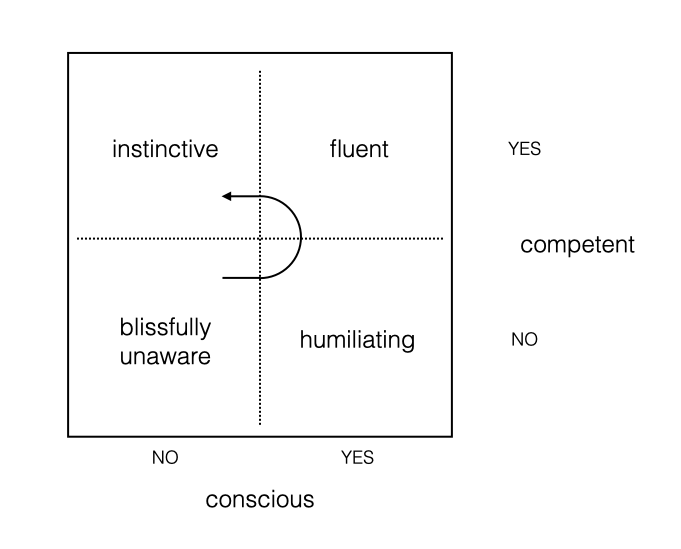

We always start blissfully unaware. We don’t know what we don’t know.

Then we realise that there is a lot we don’t know, which is humiliating and motivating or demotivating depending on our personality.

Then, over time, we start to learn and improve and become fluent. We know what we know.

Finally, it becomes instinctive. We understand and can do it without thinking about it.

These are the four stages of competence. It’s comforting to keep this in mind, especially when we’re stuck feeling humiliated and wondering if we’ll ever be fluent.

As simple as possible?

There is a famous quote, often attributed to Einstein, about simplicity:

Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.

This is a very old idea. Possibly timeless.

Interestingly, those are not the exact words that Einstein used.

This is what he actually said: 1

It can scarcely be denied that the supreme goal of all theory is to make the irreducible basic elements as simple and as few as possible without having to surrender the adequate representation of a single datum of experience.

Of course he did. He was a theoretical physicist! This is exactly how we should expect him to speak. It’s the same basic idea, just using more complicated words.

It was only later that somebody else found a simpler way to make the same point, on his behalf.2

Beyond complexity

We often talk about simplifying things. Paradoxically, when we look at people who have been successful and study their methods we find they have done the opposite: they have gotten beyond complexity.

Some people like to glorify the complicated. They talk about how long it takes for others to understand what they work on. But this just exposes that they haven’t gotten over the hump that lets them see and describe the “simplicity on the far side”.3

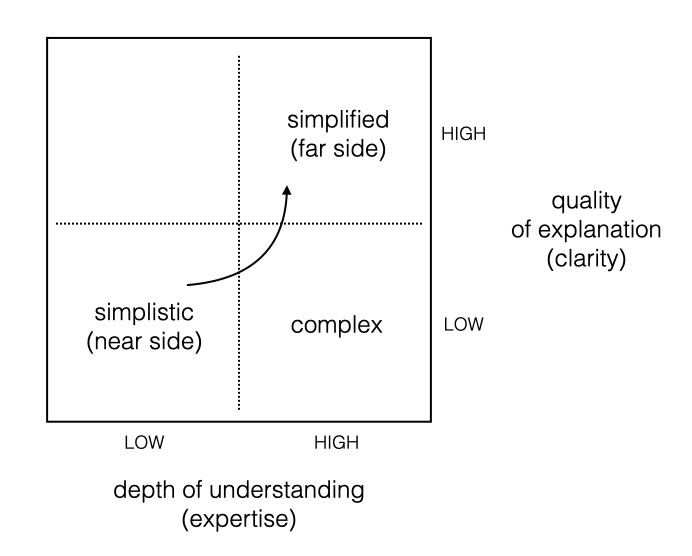

It’s not binary: simple vs. complicated.

It’s another model of progression: simplistic → complicated → simplified.

The goal in the first transition (from simplistic → complicated) is to understand the details, so we have a more complete understanding of the specific thing we’re working on. As we get into those weeds we’re going to learn the nuances, edge cases, exceptions, and trade-offs. It’s going to get complicated. But we need to keep pressing.

The key to the second transition (from complicated → simplified) is to think harder about the essence, to strip away the noise and to focus on the bits we learn, normally by painful experience, actually make a difference to performance and results.4 And then, to be able to explain that in a way that others can understand too - because it’s a very rare thing that a single brilliant individual can do by themselves.5

Who teaches the teachers?

There is a lazy expression:

Those who can: do.

Those who can’t: teach.

This is nonsense.

If you can: do. That’s hard enough.

To be a great teacher you need to be able to both do and explain it to others in a way that develops them into somebody who can do too.

The transition from simplistic to complicated to simplified or from blissfully unaware to instinctive is difficult, and rare. It inevitably involves being wrong, sometimes very wrong and for a long time. We have to be prepared to look foolish, and most people are not willing to do that.

A great teacher helps. But too many teachers have never actually done it themselves. They are also limited by an understanding that is either too simple or too complicated, so they can’t easily explain what is essential. This is especially true in the private sector where teachers are given much more impressive sounding names: mentor, adviser, director, consultant, manager, coach, etc.

When that happens the whole system breaks down.

Experts in any field usually don’t consider themselves experts. They more often behave like students - constantly seeking improvement, asking questions, trying to understand more.

Anybody calling themselves an expert is a warning sign, and often comes with a price tag attached!

The best teachers welcome dumb questions, especially if they force an explanation for why something is true or false. They know an important part of learning is being prepared to teach, and vice versa.

To get beyond complexity, avoid people who pretend that it’s easy, and that there are shortcuts. Avoid anybody who wants to drown you in complexity. Look for teachers who know why it’s hard and can explain the essential elements, and who realise that it’s better for them (and for everybody) if they can help you get to that same point too.

Related: The Cynefin Framework

-

On the Method of Theoretical Physics, Oxford lecture by Albert Einstein, 10 June 1933. ↩︎

-

Did Einstein really say that?, Nature, 30th April, 2018 ↩︎

-

Credit to David Slyfield for this expression. ↩︎

-

Shane Parish breaks this down into three steps:

- Too simplistic.

- Too complicated.

- Simple (reduction of complexity to what’s essential).

-

See: Feynman Learning Technique. ↩︎