If you call a dog’s tail a leg, how many legs does it have?

Still four, because calling a tail a leg doesn’t make it one.

I love watching elite sports people competing under pressure.

For example, this photo of the finish line of the 10,000m at the 2012 London Olympics.

The expressions on the three medallists’ faces tell a story…

First: WTF, did that really happen?

Second: OMG, I’m a white dude winning a medal in a long-distance race at the Olympics!

Third: FML

The bronze medallist on this occasion was Kenenisa Bekele from Ethiopia. The reason he’s looking a bit glum is that he was, at the time, the world record holder, so no doubt was expecting more of himself that evening.

Interestingly, this is an exception to the rule: according to research, the silver medallist is typically the least happy of the three medallists at the Olympics.1 One possible explanation for this is that silver medallists compare themselves to the gold medal winner and wonder what could have been, whereas bronze medallists compare themselves to the lower place-getters and are happy to have a medal at all.

Success is relative, remember. To be considered successful we just have to do the things that most people don’t. When the goal is to win the gold medal, doing the things that everybody on the planet except for just one other person doesn’t is … quite annoying apparently.

Pace

It’s nearly impossible for the average person, watching on television, to appreciate the speed that world-class long distance runners maintain. Bekele’s 10,000m world record was 26 minutes 17 seconds, which is the equivalent of 100 consecutive 15.8 second 100m sprints. He ran the final kilometre of that race in 2 minutes 32 seconds, and had already completed 9km at world record pace before then. That’s twice as fast as an average runner could go at full speed, starting fresh. There are only a handful of people on the planet who can sustain that pace. If you watch any of the elite marathons you’ll see the leading group contains some designated pacemakers for the first 20 or 30km. They are themselves very, very good athletes, running at an eye-watering pace, but they peel away eventually unable to stick with that speed over the critical final third of the race.

Here is a good challenge, for those of us who mostly sit on our behinds and urge others to be faster, higher and stronger: sprint one 400m lap of an athletics track. Then compare your time to Catherine Ndereba of Kenya and Zhou Chunxiu of China, who got the silver and bronze medals respectively in the marathon at the 2008 Beijing Olympics. They completed the last 400m of their race in about 76 seconds and had run over 40km before starting that final lap. 2

The gap between these athletes and ordinary people like you and me is substantial. The most obvious difference is genetic. Mo Farrah, the gold medallist above, is 1.75m (my height) but 58kg (somewhat less than my weight!) Bekele, is 54kg. That physiological difference is telling. In the history of athletics, only a small group of people have ever run sub-27 mins for the 10,000m, and Chris Solinsky, at 74kg, is the only one heavier than 65kg (he ran 26:59.6 in May 2010).

Of course, it’s much more than that. There are plenty of people born with the same genetics who never go on to athletic greatness. It takes half a lifetime of hard work to get to the start line capable of running at that pace. The media loves stories about people who come from nowhere to win, but these days performances like that are more likely to attract suspicion rather than admiration. Most champions are well signposted, with a long history of improving performances from a very young age. For example, Usain Bolt ran the 200m in 21.81 seconds in 2001, when he was 15, seven years before setting the then world record of 19.30 seconds at the Beijing Olympics in 2008, with small but consistent improvements every year in between.3 Or consider Serena Williams, as an 11 year old training against older sister Venus.4 Then, 24 years later, as a 35 year old, against the same opponent, this time in the final of the 2017 Australian Open. Incredibly they played each other 16 times in Grand Slam tournaments, with nine of those matches being finals! They brought out the best in each other.

Confidence

As I stood on the breakwater in front of the Golden Gate Yacht Club in San Francisco, on the morning of 7th September 2013, waiting for race one of the America’s Cup to start, my heart rate was noticeably higher than normal. I was just a spectator. It’s hard to comprehend how the sailors on the boat and team on shore must have felt, given what they had all personally invested in preparing for that event. Up close, the boats they were racing were more obviously fragile and bespoke - designed and constructed to sail right on the limits. Somehow those on board continue to operate and hold it all together despite those nerves. The very best seem to thrive on the pressure.

It wasn’t just physical. There was an amazing moment in the press conference after day four of racing. Team NZ were dominating the event at that stage, winning both races that day, and leading 6 to 1 overall in the first to 9 series (actually 6 to -1, as Team USA didn’t get to count their first two wins due to a penalty). USA’s skipper Jimmy Spithill was asked how he was dealing with the pressure. He looked at his rival Dean Barker sitting next time him and replied:

I think the question is: imagine if these guys lost from here. What an upset that would be. They’ve almost got it in the bag. So that’s my motivation. That would be one hell of a story, one hell of a comeback. And that’s the kind of thing that I’d like to be a part of.

Huge fighting words, and with the benefit of hindsight, quite prophetic, as Team USA eventually went on to complete what many have called the greatest comeback in sport to retain the cup 9-8. It was a remarkable level of self-confidence bordering on cockiness. And it was a deliberate strategy.5

Imagine yourself in Barker’s position, and wonder how you would respond. Not just immediately, but lying in bed trying to get to sleep that night then looking across the water on the start line the next day with Spithill grinning back at you.6

Executing the basics

If you get a chance to go to a professional rugby game, get there early and watch the teams warming up. Take some binoculars and just follow one player. If you’re anything like me, you’ll find it mesmerising to watch them run through a well considered set of exercises as they prepare for the game ahead.

There are thousands of kids in New Zealand who grow up dreaming of being an All Black or Black Fern. There are a few thousand who play at 1st XV level, and every year there are a couple of hundred who play professionally and are eligible for selection at the highest level. The breadth of that pyramid, and the competition for places and desire to be part of the team probably goes a long way to explaining why the level of performance is so impressive at the very top. It’s tempting to imagine that people in these teams are super-human. It’s better to try and understand what they do differently.

In 2011, I briefly worked on a project with some of the All Blacks players and coaches - Graham Henry, Wayne Smith, Richie McCaw and Dan Carter, amongst others. They were between their unexpected quarter-final defeat at the 2007 Rugby World Cup and their career-defining and redeeming victory at the 2011 Rugby World Cup. It was fascinating to hear them describe their roles on and off the field in their own words, and understand the thinking and methodical preparation that goes into the performances we all watch and enjoy (and heavily criticise when things, occasionally, don’t fall their way).

They have the same skills that any weekend warrior has - passing, catching, tackling, kicking - but these elite players are able to perform those skills repeatedly under extreme pressure. It’s very easy to talk about “supreme execution of the basics”.7 Actually, just executing the basics consistently and despite all that is happening around you is enough to set you apart from nearly everybody else in the world.

Are you really?

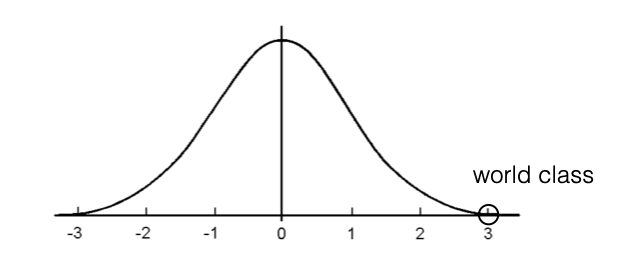

In sport there is an obvious and massive gap between the elite few and everybody else. For the enthusiastic amateur it’s tempting to bridge that gap in our mind and imagine that we could be a contender, but that doesn’t often stand up to much scrutiny. Very few amateurs call themselves world class.

However, in business this distinction is often lost. And especially in startup businesses.

The expression “world class” gets casually thrown around, like a frisbee at the beach on a sunny afternoon. But most people who use it actually have no concept of what it means.

It seems so easy to start a company and dream big. Anybody can do it, right?

I have a great idea for an app, if only I could find a developer to build it for me.

Or,

I’ve built this amazing dingus and just need to find some way to sell it

Or even more delusionally,

It will sell itself!

We need to ask at the outset: can we be world class and is that even the goal? Do we have the desire to put in the years of hard slog and dedicated focus, to be able to push ourselves to match the performance of the very best out there (keeping in mind that every founder seems to think they can do in a few years what always takes much longer)? Can we look our competitors in the eye and confidently know that we are mentally stronger and able to execute better when it counts? Can we block out the noise that others are making, and focus on our inside rather than their outside? Are the basics so ingrained, due to consistent execution over time, that we’re able to repeat them almost mindlessly, even when time and other constraints are working against us?

We don’t become world class by calling ourselves world class. Like Mo Farah, Serena Williams, Jimmy Spithill and Richie McCaw, we achieve it by competing with, and beating, the best in the world.

-

Why Bronze Medalists Are Happier Than Silver Winners, Scientific American, 9th August 2012. ↩︎

-

Final lap of women’s marathon at the 2008 Beijing Olympics, YouTube. ↩︎

-

Beijing 2008: Discovering Usain Bolt, The Science of Sport, 21st August 2008. ↩︎

-

11 and 12-year-old Venus & Serena Williams on Trans World Sport, YouTube. ↩︎

-

Spithill: I told porkies at Cup media conferences, NZ Herald. ↩︎

-

Big Year interview - Dean Barker, Radio NZ, 10th December 2013. ↩︎

-

All Blacks match Wallabies pride, NZ Herald. ↩︎

Related Essays

Head first, then feet, then heart

What could we be great at? What are we willing to take responsibility for? Combine those two things and maybe we can change the world!

Discomfort

How can understanding our relationship with pain help us conquer challenges?

Long Enough

How would treating time as a variable that we can influence change the way we behave and the choices we make?

Most People

To be considered successful we just have to do those things that most people don’t.

Picking Winners

Imagine objectively selecting companies to receive government support, without the bureaucrats or consultants?

Lessons from #RedPeak

Let it go. It’s what you learn, after you know it all, that counts.