One of the best pieces of parenting advice I ever got was:

Praise the effort, not the ability.

When we see kids doing something we like we should say “you worked hard” and “you did better than last time” not “you’re so clever”.

When we recognise and encourage behaviour it’s motivating. When we receive feedback like this it teaches us that we can improve, even if we’re not great yet. It’s an example of a “growth mindset”.1

Smart is a state. It has a limit. Effort is a habit. And often a learned skill. It can keep us going as long as we can tolerate the discomfort.

Those we perceive as brave have often just learned how to start when most people are too scared to take the plunge, and keep going when most people quit. At the same time, and just as importantly, they have the awareness to realise when something isn’t working and to change course, rather than continue to knock their head against the brick wall.

We can all think this way and see challenges as opportunities for growth rather than obstacles to avoid. We can be curious and treat any new information as a chance to learn. We can influence our own outcomes, rather than constantly feeling like victims of circumstances. We can be inspired by the great things that others do, rather than feel threatened or envious.

If we want to do anything difficult, it’s useful to understand how we cope with discomfort. What’s our typical response when things are challenging? And how can thinking about our reaction in advance help when we do find ourselves in that position?

Threshold vs Tolerance

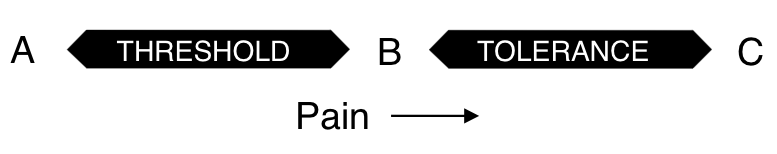

There are two dimensions: how quickly we notice the pain, and how long we can cope with it.

To help understand the difference, consider a simple physical endurance challenge. Imagine I asked you to hold a heavy weight above your head for as long as possible while trying to focus on something else, like watching a movie. At the start your arms and back will support the weight. But soon the effort becomes a distraction making it harder to focus on the movie. As time passes, eventually you will reach the point where you are unable to continue to hold the weight up and will need to drop your arms. The longer you last the more your muscles will shake and the more you’ll want to stop.

Firstly, how quickly do we get uncomfortable and start to notice the effort?

When we first lift the weight the strength in our arms and back will support the weight, allowing us to focus on the movie. But when do we first become aware of the effort and start to be distracted by that? Do we notice more-or-less immediately? Or is it some time before it starts to perceptibly hurt? What are the techniques that we use to delay that moment?

Our pain threshold (A-B in the diagram above) determines when the effort required becomes uncomfortable.

Secondly, how long can we endure discomfort?

As time passes, eventually we will reach the point where we are unable to continue to hold the weight up and will need to drop our arms. And the longer we last the more our muscles will shake and the more we’ll want to stop. How long can we delay that moment despite the difficulty? Are we able to put the goal ahead of our immediate discomfort? Or, once we’ve passed the point where it starts to be painful, do we quickly run out of motivation? What are the techniques we use to prolong that time?

Our pain tolerance (B-C in the diagram above) determines when the discomfort eventually forces us to stop.

Most of us are low on both dimensions. When attempting something difficult we get uncomfortable fast and soon after that we quit. But successful people have typically found a way to be remarkable on at least one of these dimensions.

Some may have a high pain threshold but a low pain tolerance. They are fine as long as the pain is not noticeable but as soon as it is they quickly crumble. Like Wile E Coyote in the Road Runner cartoons, who can defy gravity, but only until he looks down.Others may have a low pain threshold but a high pain tolerance. They are somehow able to compartmentalise the pain, so it doesn’t distract from the task at hand. Like an athlete pushing themselves to the physical limit who is able stay calm and keep going when most of us would stop. The ultimate is to combine a high threshold with a high tolerance. But that’s extremely rare. Those people win medals.

All the things

We can apply this same idea to anything that’s difficult, including things that are much more mental than physical. For example, when we learn a complex new skill like speaking a foreign language or playing a musical instrument. We can break the things that are hard into these two components: How far do we get before we become aware of, and distracted by, what we’re not already good at? This is our threshold for learning. When it’s difficult, is our instinct to stop, or do we continue, knowing that it is normally hard? Can we stay focused on the goal and reason that we started, or do we get overwhelmed by the frustration in the moment? This is our tolerance for learning.

Similarly, think about how we cope with the risks involved in a new venture. Where do we perceive risk? At what point in the process of exploring a new idea do we turn our minds to the likelihood of failure? Do we need to understand every possible concern, or are we happy to start and see what happens? This is our risk threshold. Once we’re aware of the risks we’re taking, how comfortable are we in the moment? Do we freeze and worry constantly, unable to act or becoming indecisive about what to do next, or can we be aware of the risks we’re facing but keep moving anyway? This is our risk tolerance.

Our threshold and our tolerance are often very different depending on the challenge we’re facing. We might be highly risk-averse when it comes to our finances, but enjoy parkour. We might give up holding the weight over our head very quickly, because it feels pointless, but hike for miles even when our feet ache to conquer a particular track or catch an amazing view. Our environment also has a big influence. The classic example of this is the generation of people who grew up during the Great Depression, who later in life tended to stick to their views on saving and spending, even after the economic conditions had significantly improved.

Delta

If we want to get better at anything these two dimensions are separate things to work on.

A low threshold tends to be physiological rather than psychological. So, like a mountain climber who stops at base camp while their body adjusts to the altitude, we need to invest the time until we normalise the situation we want to cope with and our response becomes more automatic. The sooner we start the better.

A low tolerance, meanwhile, is more in our head, and so much more malleable.2 We have to keep the end in mind (constantly reinforcing why it is important to us) and learn techniques to trick ourselves into thinking differently about our situation – remaining calm when our natural instinct is to get angry or flustered, or narrowing our focus, rather than getting distracted by our environment.

Increasing our tolerance requires a combination of keeping the end in mind (constantly reinforcing why we are doing this) and learning the techniques we can use in the moment to trick ourselves into thinking differently about our situation - e.g. remaining calm when our natural instinct is to get angry or flustered, or narrowing our focus, rather than getting distracted by our environment.

If we work on both of those things, we’ll increase our overall ability to deal with discomfort and complete difficult things.

-

Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, by Carol Dweck.

Also: Developing a Growth Mindset, Stanford Alumni ↩︎

-

In her book Grit, Angela Duckworth describes this with a simple formula:

Talents x Effort = SkillSkill x Effort = AchievementOur talents determine how quickly we improve when we invest time, but the effort we put in counts much more towards what we ultimately achieve. If this formula is correct we can simplify it further:

Achievement = Talents x Effort ^2This is why it’s important we have a growth mindset. Our talents might be fixed but the effort we put in is variable. And that has a big impact on the results we achieve. ↩︎

Related Essays

Scar Tissue

Working on a startup is much more like racing a BMX bike than riding a roller coaster.

World Class

The expression “world class” gets casually thrown around, like a frisbee at the beach. But what does it really mean?

The Plunge

Why do the most interesting bits of startup stories always get airbrushed out?

Long Enough

How would treating time as a variable that we can influence change the way we behave and the choices we make?

Anything vs Everything

How do we choose what to focus on, and have the conviction to say “no” to everything else?

Monochrome

What can rugby teams and rowing squads teach us about building and managing diverse teams?

Buy the book