There will come a time when you believe everything is finished. That will be the beginning.

How do we turn promising ideas into real products people can use?

It’s said a successful product team needs three key people: 1

- A developer

- A designer

- A dictator

I have a Computer Science degree, so I can code. And I’ve been fortunate in my career to work with some really great designers who have taught me many of their tricks, so I can design a little too. But, if I’m honest, I’m not world class at either of those things. I realised I’d need to become a good dictator.

There is no shortage of advice about how to be a good designer or a good software developer. But much less about effective dictatorship.

The last job title I had at Trade Me was “Head of Product”. Most people understand what it means to be a software developer. But I’ve never seen a succinct definition of a product manager.

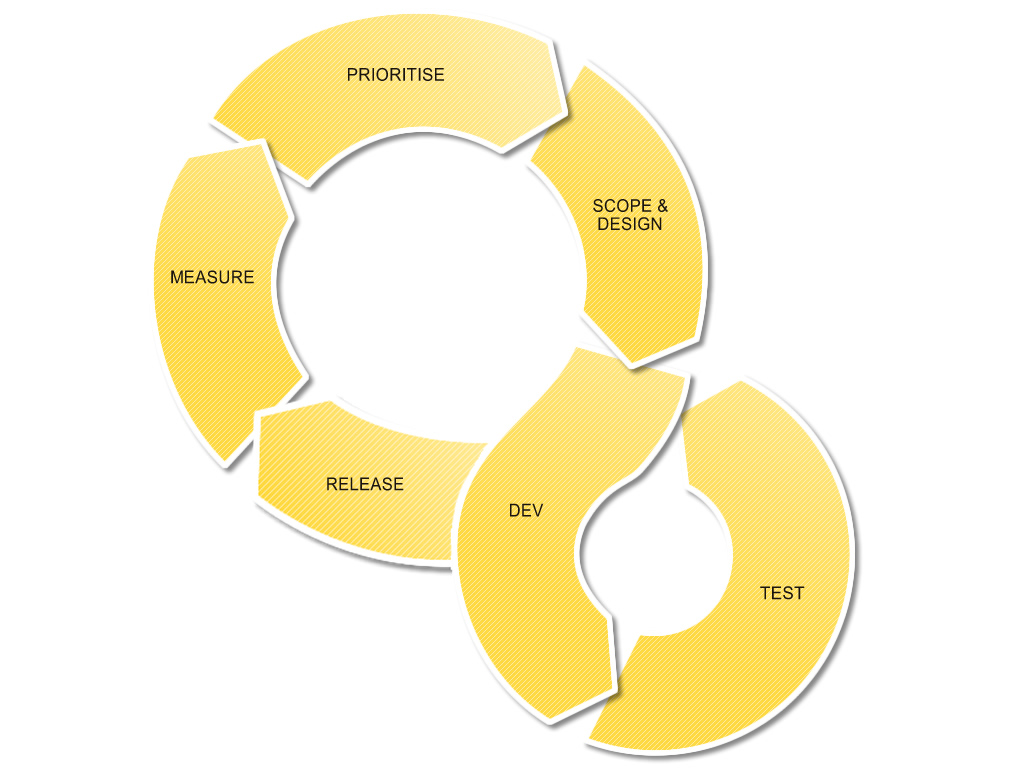

This is the product development process we used at Trade Me, and the best way I have to explain the role. It could be used by any team, whether it’s brand new (as Trade Me was then) or decades old (as Trade Me is now). There are six steps in two loops.

Most software development teams now use some variation of an Agile process.2 While we didn’t have that terminology back then, we did use many of the same practices in the smaller loop. So let’s focus on the larger “product management” loop, and pick it up at the point where we are ready to deploy a new feature out into the wild…

Release

The first and most important thing about any product release is it’s not an end point. It’s just another link in an infinite loop. I like to have in mind a slot car set. The track is endless – the start is also the finish. When we think we’re done, that’s the beginning of the next lap.3

This can be tough to understand for technical people who have predominantly worked on projects that have a well-defined beginning and end, at which point everybody involved moves onto the next project and the software moves into “business-as-usual” or maintenance mode. When we manage a product there is only business-as-usual. We are never finished. This has a number of consequences, not the least being the importance of pacing ourselves. Product management is a never-ending slow and steady trek, not a sprint or a death march.

The second important thing about the release cycle is how we win. It’s tempting to think it’s about getting everything right. But, remember, we will never be finished. “Everything right” is a mirage. There is no such thing. However, there is such a thing as late. The trade-off between right and late is what makes product management more art than science. Reid Hoffman, an early employee at PayPal and later founder of LinkedIn, has some excellent advice: “If we launch and we’re not a little embarrassed then we launched too late.” The only way to learn which parts we need to be embarrassed about later is by launching and listening carefully to the feedback we get. For this reason, the best product managers typically have a bias for action and calculated risk-taking. If there are no missteps then we’re probably playing it too safe. To quote software engineer Kent Beck, we need to “trade the dream of success for the reality of feedback”.

Our challenge is not to navigate flawlessly once around this loop, but to navigate our way around as many times as we can, getting a little bit better each time.

At Trade Me I learned that some release theatre can help, so that everybody on the team is aware when new features or even small fixes are deployed and can celebrate the incremental progress that represents. Our test team, who had final sign-off on each release (twice per day at that point), got into the habit of playing ‘Push the Button’ by the Sugababes on the MP3 player when they were ready for changes to be deployed to production. Every time I hear that song now my pulse increases slightly at the prospect of some site changes going live. My only regret is failing to follow through on my intention to wire up an actual big red button for them to push to trigger the deployment.

Measure

As soon as we make changes, the next challenge is to create a feedback loop. This is where we see what people do. Have the changes we’ve just made had the intended impact? Do people click on the new link or buy the new product? Understanding how people use what we’ve made helps us to cut through debate in the next two steps of the process with facts rather than feelings. It’s how we build a mental model about what customers respond to. This doesn’t always mean doing what customers love. Often it’s a product manager’s job to do what is best for the business as a whole, rather than for individual customers.

The whole team should know what the key metrics are and how the business wins, so we stay focused on the things that matter. We can highlight both the current values and the trends, whether on a big screen on the office wall or a shared online dashboard. We should always be able to articulate how any particular feature we are working on will positively impact those numbers.

Prioritise

The job of a product manager is to manage infinite lists. We have to take inputs from lots of different and often competing sources and constantly organise these so that the priorities bubble to the top and we don’t drown in the long tail of less important stuff.

It’s not enough to say “we need to focus” or “we need to prioritise”. Those are just intentions. Telling somebody who has lots of options to focus is as unhelpful as telling somebody having a panic attack to calm down. Unfortunately, being focused or having well-defined priorities isn’t something that just happens by accident. It requires constant work. It’s easy to assume that focus means saying “yes” to the small number of things that need our attention. Actually it’s about saying “no” to the hundreds of other things that would be distractions.

The hard part is identifying those distractions. The even harder part is not spending time on them. Here are two techniques that helped me.

Talk to the hand

I learned the first technique the hard way at Trade Me and I now recommend it to anybody struggling with overwhelm. The good news is you already have the tools you need to use it, literally at your fingertips – you just have to remember it.

In those days I would regularly be bombarded with new ideas for new features. And they were often great ideas. But we could only do so much, and eventually trying to keep everything in my head became exhausting. So instead I would just keep in mind the top five strategic priorities – things that would require multiple weeks or months of work. Then whenever a new project was suggested the question wasn’t “is this a good idea?” but rather “which of our existing priorities gets bumped by this new suggestion?”

I would sometimes hold out the palm of my hand and spread my fingers when asking this question of anybody suggesting a new priority – partly to emphasise the constraint of five things, but also because it helped me to remember what the five current things were.

More often than not the decision was that the current priorities were correct. We were able to continue without adding new distractions. And in the rare situations where we did choose to swap our priorities, because the new idea was just too good to delay, we did that consciously and the costs were explicit.

It’s powerful if there is consensus in the team about the priority projects. A useful technique is to organise a prioritisation session where everybody is asked to bring their own top two or three ideas to the table and advocate for them. Then, as a group, rank them all in terms of bang (the expected impact on key metrics) vs. buck (the expected cost to implement). Finally, pick the ideas which have the best ratio. Ideally nobody leaves until everybody has agreed what those are.

It also helps to have somewhere to dump everything else. And for any non-trivial product everything else can be a lot. It may be that we don’t even need to write these things down. If we’re prepared to assume that good ideas will keep coming up. Or, maybe having a long shopping list lets us quickly fill any gaps that appear with something useful. Either way, the key is to ensure that these don’t become a constant distraction or an overwhelming backlog that makes it difficult to keep going on the things that need to come first.

Remember we’ll never be finished, so getting to the end of the list is not the goal. Focus means doing less. We can be busy or remarkable, but probably not both.

Top Three

The second is a variation of the same concept, but applied to personal priorities:

At the end of the day write down the three most important things you need to complete the next day. Then tomorrow, do those things first.

The actual number of things doesn’t really matter – I choose three rather than five in this case because that’s the most I can usually get done in one day, but your mileage may vary.

It’s an elegant and simple idea, and pretty much the polar opposite of every other productivity system. Rather than combining more and more complex ways of capturing, storing, sorting and retrieving lists of tasks it’s all about narrowing focus and getting important stuff done.

But don’t confuse simple with easy. It’s chastening how often I get to the end of a day or even the end of a week and realise that I didn’t complete even one of my three priorities. The immediate feedback loop from this repeated failure might be the secret that makes this technique effective over the longer term: it highlights the distractions that get in the way of the important things. And the beauty of it is that each day we get three new slots to fill – so it doesn’t accumulate distracting cruft.

We don’t have to think too hard about our priorities. We can just pay attention to what we do first each day. Our real priorities are revealed, not stated. Often what we do betrays what we say. Our stated priorities are hopeful, but our revealed priorities are honest. When we design and build a product or service that we hope others will use and pay for and tell their friends about, it’s helpful to listen for stated preferences, but it’s much more important to watch for revealed preferences. It’s dangerous to base our optimism entirely on kind words. We need to always cut through and find some action that demonstrates that people mean what they say.

Scope & design

After all of the work that goes into wrestling priorities and maintaining focus, it also pays to keep in mind Noah’s rule: it’s not enough to predict rain, you have to actually build an ark. What counts in the end are the things we complete, despite distractions. This fourth link in the chain is where a good product manager should invest most of their time, contending with the trade-off between slow, expensive or crappy.

Scope, as I discovered at Trade Me, is the often overlooked fourth variable. It’s the line we draw in advance to define our expectations. We need to ask: What are the anticipated features of the thing we’re making? (Technical people call this “functionality”, but I’ve discovered that term is meaningless to normal people.) What can customers do with it? And what is it for?

Scope is nearly always what gets cut when the pressure comes on, to work within the other three constraints. Again, sometimes this is appropriate. It’s nearly impossible to define scope specifically in advance, and when we eventually discover the flaws in our assumptions it’s usually better to adjust the plans than to be stubborn. But it’s often just the easiest thing to compromise on. It’s better to be clear about what aspects will demonstrate value to paying customers. Then extrapolate from there based on how people use it. Implement a subset of features really well, rather than partially building the whole product and ending up with a lot of compromises.

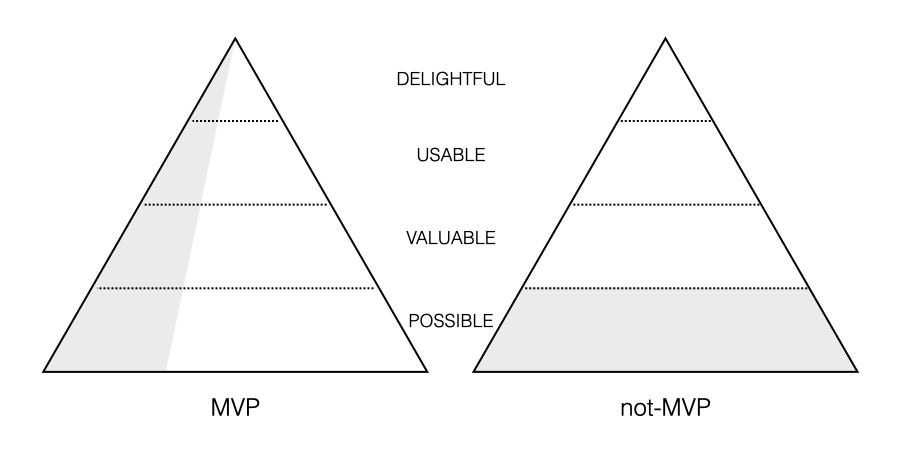

Startups these days frequently talk about building a minimal viable product, as a way to constrain scope. But the idea of an MVP is not to just build what is possible, it’s to build something small to quickly demonstrate the product’s potential, to give a sense of what is valuable, usable and hopefully delightful.

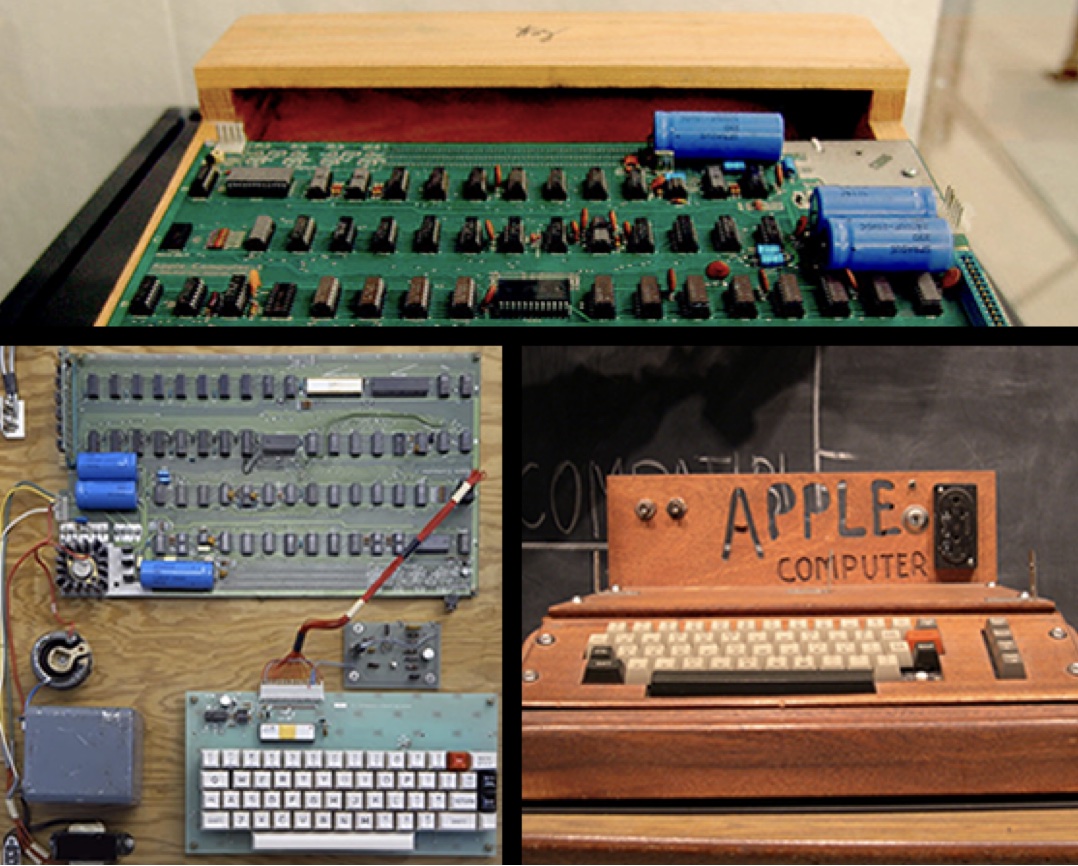

When technical people hear MVP many will imagine something like the original iPhone from 2007. And it’s true, as with any product, the team at Apple building the first edition iPhone had to make a lot of compromises: a small touch screen (the resolution was just 320 x 480 pixels, about 20% of the size of current models, and with only one-third the pixel density); no front-facing camera or video recording; no third-party apps or App Store; no GPS or 3G connections; and many missing software features we now take for granted like copy-and-paste. But the context is important too. The iPhone team at Apple were building on the massive success of the iPod and the legacy of the Mac and MacBook products. Most startup teams can only dream of those advantages. A more relevant example is to rewind to when Apple was itself a startup, and consider the original Apple I computer. It looks much more like an electronics kitset than a computer. Our definition of MVP depends a lot on the resources that we have, both time and money, and we need to set our scope accordingly.

Once we realise that the most important thing is what the customer actually does, not what the software can theoretically do, everything should focus on the user experience.

We should be able to describe the change are we expecting once this feature is released and how we will measure that. This question creates the feedback loop, so we can confirm that the work we’ve done has had the intended impact, or not, and learn from that for future scoping and design work. If we can’t clearly articulate what the intended change or benefit is, then we need to think more before we start designing the user experience or writing code.

As scope and design bleeds into development and testing the product manager will hand over to a development manager to make sure that the build runs smoothly, and will likely become a customer in that process. In a smaller team the product manager and development manager are often the same person, so it’s important for them to realise the two competing roles they fill.

Everything & nothing

Being a great product manager demands a wide range of skills. We need to have empathy for users: who they are, how they think about our product and how they are likely to respond in different situations. We need to think analytically. We’ll spend more time looking at spreadsheets than looking at code. On the other hand, we need aesthetic judgement, a sense of style and an understanding of design trade-offs. We need to write clearly and communicate well with others, both internally and externally. We need to think like a marketer, because making things that people will love is hard. We need to be comfortable working with a variety of different people, both technical and non-technical. Last but not least, it helps to be low-ego because often nobody will notice the work unless things go wrong.

Product managers need to be a bridge between the product team and the customer. In the early stages we also fill any gaps. For example, if there is no sales team then we are the sales team. If we come from a technical background we need to build our skills in these other areas. It’s rare that a product manager is great at all these things. The best product managers I’ve worked with are heads-up developers who can code but don’t want to any more. Those who aren’t technical need at least to understand enough about how the product is built so they can communicate effectively.

A great product manager helps teams create products that customers love.

-

The Engineer, The Designer, And The Dictator, Michael Lopp. ↩︎

-

Agile software development, Wikipedia. ↩︎

-

Lonely on the Mountain, by Louis L’Amour. ↩︎

Related Essays

Being Spartan with Ideas

Do you leave your ideas to fend for themselves in the wild or keep them in a safe place?

The Pit of Success

It’s not what the software does, it’s what the user does that matters.

Anything vs Everything

How do we choose what to focus on, and have the conviction to say “no” to everything else?