Money is like gas in the car — you need to pay attention or you’ll end up on the side of the road — but a well-lived life is not a tour of gas stations

By far the most common question I am asked as an early-stage investor is not how to grow a successful business or build a great team, but how to raise more capital. It often feels like getting investment has become an end in itself.

Diluting our ownership of a rapidly growing company, which we believe is going to be worth much more in the future, may seem irrational. But that’s exactly what we’re doing when we raise capital. To justify this we have to believe that the benefits will outweigh the costs.

It’s important that three things are true:

-

We have some momentum, even if the numbers are small. If we cannot show potential investors that we’ve already got some wind in our sails then it’s much more work to convince them to invest. We could spend that time on more important things, like getting the boat moving.

-

We know exactly what we’re going to spend the money on. If the answer is (as it always is) mostly “people and rent” then be more specific about what roles we need to fill and how much it will cost to fill them, including the total cost of having a larger team beyond just the salary costs - e.g. recruitment fees, equipment, office costs or the additional costs of running a useful remote team, etc - plus the harder to quantify distractions that come from having more people involved.

-

We have the next milestone in mind. Ideally we’re thinking at least two moves ahead…

Begin with the end in mind

When we don’t know where we’re going then any road leads us there.

When we’re deciding how to fund our startup we need to ask: What kind of business are we hoping to build, and who is the best partner to help us achieve that?

The first question is whether we should raise outside capital at all.

In simple terms there are three ways to approach an early-stage business:

1. Burn baby, burn!

We can raise as much money as we can up-front, then spend it aggressively in pursuit of revenue.

If we choose this option, it’s critical that we commit to it and paint a big picture for investors. Before they give us money they need to believe there is a chance they will get a much larger amount back in time. That means they need us to continue to grow, rapidly, and that we will (at some point) achieve liquidity for them by selling the business or taking it to the public markets through an IPO. It’s a one-way street. Once we’ve taken investment there is no option for us to ease off the accelerator and say “this is where we’d like to stop; the team’s big enough, we’ve worked hard enough, we’re going to relax and enjoy the fruits of our labour now.” 1

The problem with this approach is the uncertainty. Perhaps there won’t be quite as many customers as we think, or perhaps it will take us longer than we thought to convince them to buy, or maybe it will be much harder to build the team we need to help us get there than we expected. Either way, there is a possibility that we will spend all the money we raised before we get enough revenue to cover our costs into the future.

Unless we can continue to build momentum and find a way to tell an even bigger story, we’ll find it difficult to raise more money when required. Then we need to flip from a high-cost model to a low-cost model, which isn’t fun when we’ve hired people we like. Growing quickly is hard. Shrinking quickly is harder.

On the other hand, if we’re successful then we can end up owning a share of a business that is much larger than we could have created on our own.

2. 2-minute noodles

Or we can keep our costs as low as possible for as long as possible, and try to quickly get to a cash-flow positive position.

Maybe we can fund those early stages ourselves from savings, or maybe we can find a patient benefactor who is prepared to invest a modest amount of capital. Either way, we need to make a small amount of cash go a long way. Ideally all the way to a profitable business (or at least one that washes its own face).

However, there are two obvious problems with this approach:

It’s only really possible if we’re young (or stupid). Older people tend to already have too many expensive tastes and existing commitments and responsibilities.

And it can take forever, so we need to be patient. In the meantime perhaps somebody else will come along with more resources (see “Burn baby, burn” above) and win our customers before we can get to them. Or, maybe it requires more investment (both time and money) than we have?

Of course, if it does work, we are left owning most of a business that’s paying for itself, and generating cash. That puts us in a strong position to talk to potential investors, to re-invest in growing the business further ourselves, or to simply sit back and enjoy the profits.

3. Hybrid

Alternatively we can use revenue from consulting or other part-time work to fund our venture. In other words, spend some of our time working for other people, so we have enough money to fund our own ideas.

The obvious risk is that we find it difficult to wean ourselves off our dependence on the comfortable salary our consulting work provides.

Or perhaps we find it difficult to say “no” to work when it is available, and as a result the consulting work takes all our time leaving little space for anything else.

If we can find the right balance, this is a great way to fund a business without having to constantly scrimp and save and do everything cheaply, and without having to raise money from needy external investors.

There are examples of great companies that have taken each of these approaches, so it’s impossible to say which is “best”. We need to be careful whose advice we take. Anybody who has been successful in the past usually recommends the approach that worked for them.

The important thing is to choose. Don’t get stuck halfway between options, taking on investment (with the associated expectations that brings) but not really raising enough money to really go hard, or taking a “hybrid” approach while also taking on external shareholders.

And never forget, how we fund our venture or how much capital we raise is ultimately irrelevant unless we make something people want and can sell it to them for less than it costs us to make it.

Investor motives

Once we have decided that raising capital is what we want, the next most important question to ask is: “who?”

Nearly everybody starts with questions like “how much?” or “at what valuation?” or even “how quickly?”

But the best founders choose their investors carefully, not only for how much cash they can invest but also for how much they can help the venture get to the next milestone. So think about who would contribute the most in the next stage, then work out what we need to be in order to convince them to invest and join the team. Then ask them to invest.

Understanding exactly what motivates different types of investors allows us to adjust how we present the opportunity to them. It’s difficult to convince somebody whose job depends on not being convinced.

Some of the common motives are:

1. Story

Some investors are attracted by the apparent glamour of early-stage ventures. They like to tell their friends and colleagues that they are involved in something that sounds exciting.

We need to offer these investors some recognition for their involvement, even if it’s small.

2. Contribution

Some investors are looking for something to spend their time on, and prefer to leverage that investment with a small financial stake.

We need to offer these investors a role where they feel they are involved and making a difference.

3. Return on Investment (ROI)

Some investors are simply looking for a financial return.

Eventually they want to get back more than they invested, plus some extra for the risk they took. That could be shares they can sell (what is often called “liquidity”), cash from an exit, or maybe on-going dividends.

We need to understand what returns they are expecting. This will likely depend on their personal circumstances, or the mandate of their fund, and also how early they are investing. We need a forecast that gives them confidence that if things go well an outcome like that is possible.

However, always be honest about how accurate future predictions are, especially in the early stages. Investors asking for a multi-year forecast, before there is enough data to make good assumptions, are asking us to lie to them. We should call them on that.2

4. Carry

Some investors who manage a fund on behalf of others are compensated based on the size of the fund and the overall capital gain they produce for their funders.

For example, a general partner in a venture capital fund will typically receive 2% + 20%, meaning they are paid 2% of the total value of the fund they manage every year, to cover the fixed costs of running the fund, plus 20% of any gains.3

We need to convince these investors that we have a chance of knocking it out of the park - because they are investing in a portfolio of companies alongside ours, there is not much difference for them between a mild success and a complete failure, so they will expect us to be swinging for the fences.

5. Uplift

Some investors who manage a fund on behalf of others are compensated based on the current value of those investments.

For example, a hedge fund will typically pay managers an annual bonus based on the increase in value. This effectively means they buy the shares again every year.

We need to show these investors that we can steadily increase the value of the business over time and avoid any nasty shocks which could cause the value to drop from one year to the next.

Think about what kind of investor is the best fit, given the stage we’re at and our own ambitions for the future. It’s surprising how often there is a complete mismatch between the motivations of founders and investors as a venture grows.

If we’re just getting started and need to raise a small amount of capital to cover costs while we explore the opportunity, then we’ll probably struggle to get larger investors excited, given they generally prefer to invest bigger amounts once there is an obvious way that this money can be used to remove constraints and accelerate the growth of the business.

More than this, it can sometimes be toxic to get a high profile investor on board in the first round - in the next round other investors will take the lead from them, and if they choose not to continue investing, for any reason, then we’ll likely struggle to explain to others why they should think differently.

Conversely, once we’re ready for larger amounts of capital to help accelerate, then it’s a waste of time to continue pitching to investors who are mostly interested in the story or contributing their time, but who normally don’t write big cheques.

If our goal is to create a business that will pay a good salary to founders and maybe a few employees, then we’re creating a future headache for ourselves if we raise any money from financial investors who are driven by a return.

Have this conversation explicitly with potential investors. If it’s not clear in advance which type of investor we’re talking to then take some time to understand what is attracting them to this venture.

Investors are like a puppy for Christmas. We can’t just hand them back when we get tired of them or ignore them when they need attention. So choosing the right investors is a critical decision. We can look at the track record from previous ventures as a guide. Look for investors who have consistently demonstrated they add more value than they capture for themselves. Over time I believe the best opportunities will flow to investors who consistently do that for founders.

I realised…

Once we’ve chosen our ideal investors we need to convince them to invest. The most effective investment pitches all start with the same two words.

Most product-centric founders start their pitch by demonstrating a solution. They describe what they’ve built or hope to build, particularly when the solutions involves genuine innovation or invention.

Sales people usually start by describing the problem, and their vision for how that problem might be solved.

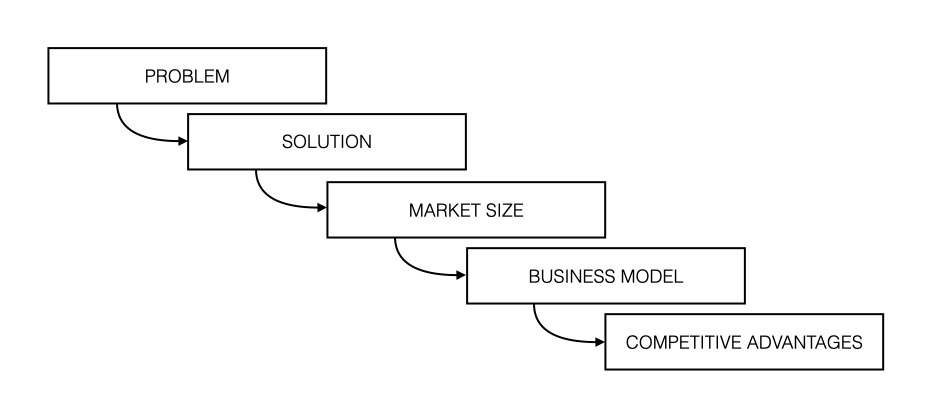

This approach became popular some years ago after the original Airbnb pitch deck was shared.4 This simple format they popularised was widely adopted:

Finance people typically start their pitch with numbers.

When we have metrics that demonstrate momentum and market validation then it’s tempting to just share those and let potential investors extrapolate. The great thing about results, even if they are very early or building on a small base, is that they stick in the mind of the person receiving the pitch much more effectively than promises. But facts can also easily ruin a great story, so we need to make sure all of the numbers are good, or at least be prepared to explain those that are not.

However, after hearing a lot of them, I’ve realised the most compelling pitches take a very different approach:

Start with the insights gained from the experiments completed so far.

The most valuable insights combine a lesson learned from experience with a proposed next step. They are small actionable units of truth.5 So, try to start a pitch with these two words: we realised…

Leading with insights allows us to explain how our understanding of the problem and the solution we are working on have evolved over time, and can continue to improve, rather than requiring us to pretend that we already have the answers. It avoids the common deceit of needing to present a solid and unchanging vision for the future (remember what Yoda said: the future is always in motion). It’s also a great way to demonstrate our competitive advantage - it’s hard to catch another team who are learning faster.

To solve any problem we need to experiment. If we haven’t completed any experiments yet, and so don’t have any useful insights to share yet, that’s a sign that we’re probably not ready to pitch for investment.

The round about

Once we’ve chosen the investors we want and convinced them to join the team, the next job is to work with them to agree terms everybody is happy with.

We need to make sure the bigger investors are putting enough cash in, and getting enough of a percentage in return, so that they care about the venture and will invest their time and energy and networks into making it a success in the future.

A lead investor will help to shape a round. Some investors will be happy to go alone. Others prefer to invest alongside others. The important thing is to start with the larger investors first and ask them to help us fill whatever amount is left over for smaller investors. It is frustratingly common for founders to do this in the reverse order, which is nearly always a mistake.

A lead investor should be someone who has the capacity to invest in subsequent rounds. Ideally they should also have a network of connections to help in the future with intros to larger and larger investors.

A lead investor will also help to set the valuation.

It might sound overly simplistic, but it’s something that the market decides. The price is whatever an investor will offer and whatever founders will stomach, and hopefully there is some overlap between those two.

These are two rules of thumb that I use:

- Expect to dilute between 20-30% per round, so that there is enough equity available to new investors to ensure we have their attention into the future; and

- Plan to raise enough to cover 18-24 months’ worth of expenses, based on a well documented and easily communicated plan that estimates what these are likely to be

Given those constraints we can solve the equation and give ourselves a range to start the discussion with.

It gets more complicated if we already have customers and revenue and a growth trajectory, since that gives some basis for a valuation based on fundamentals. For example, investors will often look at a multiple of annualised revenue when considering the valuation of a SaaS business. However, at an early-stage when the numbers are small that often ends up being in the range I mentioned above anyway. Remember that numbers can easily mess up a good story.

Try not to get bogged down in this. At the end of the day neither founders or investors win because they eked the last percentage point of ownership or dilution out of a funding round negotiation, we win by working together to build a fast-growing ass-kicking name-taking business. In the not too distant future whatever valuation we agree now is likely to either look way too high (because the company is dead and therefore worthless) or way too low (because it became a big success).

Don’t pretend to be something we’re not and don’t die in the ditch over terms that probably won’t matter down the track.

Cleared for take-off

We should be clear from the outset, with ourselves and our co-founders, about what kind of business we’re hoping to build. If investment is part of the plan, choose aligned investors who will help us get where we’re going. Then negotiate an investment from them that leaves everyone motivated to see the business succeed.

If we do that, we should acknowledge the applause but not be distracted by it, because now we’re sitting at the end of the runway, and we need to fly the plane…!

-

Surviving The Sharks, Sacha Judd at Microsoft TechEd, 2014. ↩︎

-

Matt Mireles said it best:

↩︎One of the red flags I look for is seed investors that want me to make things up and lie to them. This typically manifests itself in the form of long-term financial projections. “What will your sales be 5 years from now?” I have no fucking clue, and if you’re asking me that question, neither do you. I am a first-time founder in an immature, rapidly growing market. Pricing, exact business model — these things are all up in the air. My task now is to go out and prove certain assumptions about the product and the market in a way that we matched the two up and achieve the magical paradise that is product-market fit. Before I’ve done that, don’t ask me for financial projections other than my expenses, because what you’re really doing is asking me to lie to you, and I hate that.

-

Venture Fund Economics by Fred Wilson, August 2008. ↩︎

-

Writing a business plan, Sequoia Capital. ↩︎

-

Kunal Shah: Core Human Motivations, Knowledge Project Podcast, Episode 141. ↩︎

Related Essays

How to Pitch

We realised that the most effective investment pitches all start with the same two words…

Anything vs Everything

How do we choose what to focus on, and have the conviction to say “no” to everything else?

Diworsification

A portfolio approach to early-stage venture investment doesn’t really help and probably hurts.

M3: The Metrics Maturity Model

Use these simple steps to improve how we measure and report our progress.

Pining for the Fjords

Be honest: Can we get to the next milestone with the resources we have?