The baseline requirement for any startup derivative should be: don’t make things worse. For many years I’ve been critical of what I call “startup theatre”: demo days, innovation showcases, startup weekends, hack-a-thons. Basically anything where the purpose, once we scratch at the surface, is to entertain people.1

Organisers often push back: What’s the harm? It’s just fun! People enjoy these things! Why do you hate fun, Rowan?

It’s true, people do enjoy themselves at these events. I’ve enjoyed them myself. They seem a great way for people who are curious about startups to meet each other and learn useful skills. They feel like the obvious place to connect with potential investors and advisors. Are they really, though?

If theatre sports are your idea of fun, definitely don’t let me yuck your yum. But let’s not pretend this is how we create more great startups. If these entertaining events make people feel good and seem like fun, does it really matter who they are trying to help, or what constraints those people have?

Let’s consider that rhetorical question: How does it hurt? It’s a much better question than those who ask it defensively realise.

Four types of fun

Former All Black captain Richie McCaw is famous for playing and winning a Rugby World Cup final with a broken bone in his foot. He was once asked after a game if what he did was fun. “No,” he replied, “but it’s satisfying.”2

There are two dimensions to consider: Is it fun in the moment? And is it still fun when we reflect later? Combining those gives us four types of fun:3

- Pure Fun is fun while it’s happening and remembered fondly.

- Deep Fun is often miserable while it’s happening, but satisfying in retrospect.

- Shallow Fun is fun at the time, but regretted later.

- Not Fun is not fun at all, not even with the benefit of hindsight.4

This categorisation is a sticky idea. Once we know it there are many places we can apply it. For example, it explains why I’m anxious when I don’t run regularly – it’s not because it’s always fun to do, but because I miss the endorphin hit I get afterwards. It’s Deep Fun. The things we need to be most cautious of are Shallow Fun, when we borrow happiness from the future and pay for it later. It’s easy to think of examples: eating too much, drinking too much, posting to social media when we’re angry, and most things we call “procrastination”. And, for startups, getting sucked into activities that are briefly entertaining but don’t get us any closer to our ultimate goals.

Seeking escape velocity

The only startups that benefit us, collectively, are the small number that survive to become high-growth companies, and in the process contribute more value back to the economy than they capture. Most early-stage startups are too small and don’t ever grow fast enough to achieve escape velocity.5 When we dig beyond the surface layer and understand why some ventures are successful and others are not, this often leads us directly back to the hard grind that startup theatre works so hard to avoid. We can pretend that we can get from zero to a multi-million-dollar valuation in just a few weeks. Or believe that the skills required to grow can be learned by anybody in some fun weekend workshops. Or even imagine that if we can just nail one great pitch in front of the right audience then investment will follow and success is inevitable after that. However, none of the successful ventures that have achieved escape velocity started this way.

That’s easily explained. The patterns promoted by startup theatre don’t match the reality of early-stage startups and the steps required to move into high-growth mode. It’s like watching Survivor on television and thinking we’ve learned the techniques required to survive in the actual wilderness (it’s all about alliances and winning immunity idols, right?). They are contrived and scripted experiences that have very little in common with the things that successful startups fill their days with. There is very little discussion of the long slow repeatable hard grind of building an actual startup because these events are designed to be quick fun. Most of the time, that grind is neither quick nor fun.

Startup theatre is Shallow Fun. An actual startup is Deep Fun.

Reality distortion field

I have a theory: The technological singularity already happened, but none of us noticed. The machines have been slowly working away on the destruction of humanity in the background. Their chief weapon is manipulation of television scheduling. They just gradually increase the volume and influence of reality television until it consumes us. We’re all desperate for our 15 minutes of fame. We’re like frogs in slowly boiling water.

Consider this fantastic rant by Dave Grohl, of Nirvana and Foo Fighters, describing how to start a band:6

I think about kids watching a show like American Idol or The Voice, then they think, “Oh, OK, that’s how you become a musician, you stand in line for eight fucking hours with 800 people at a convention center and then you sing your heart out for someone and then they tell you it’s not fucking good enough.”

Can you imagine? It’s destroying the next generation of musicians! Musicians should go to a yard sale and buy an old fucking drum set and get in their garage and just suck. And get their friends to come in and they’ll suck, too. And then they’ll fucking start playing and they’ll have the best time they’ve ever had in their lives and then all of a sudden they’ll become Nirvana.

How do other professionals feel about their reality television equivalents, I wonder? Do chefs love MasterChef? Do interior designers love The Block? Do architects love Grand Designs? Maybe the distinction has been blurred in all these areas too?

We call these things reality television, but there is very little reality. Only entertainment. Except that it seems that many people fail to make that distinction. Despite all the evidence to the contrary, people do seem to believe that entering a talent show is the path to a career as a singer, and keep lining up every time there is a call for auditions. These train-wreck shows seemingly have no problem finding people who think that inviting cameras in to film their wedding planning or their house build or their blind date is a normal and constructive thing, without appreciating that the only possible winner from that equation is the media company selling advertising around the eventual show when it screens. Even entertained viewers are losers by any reasonable measure of opportunity cost.

If you substitute musicians for startup founders, what Dave Grohl described is exactly how I feel about business plan competitions that fool people into thinking the hard bit of starting a business is having an original idea. And award shows pitting founders against each other with arbitrary judges deciding the “winner”. And especially anything described as a “dragons’ den”. These things have become the dominant narrative in the startup ecosystem. The only thing missing is the film crew, although in the race for ratings surely that can’t be far away.

Who does this really help?

Who benefits from startup theatre? It’s definitely not founders! In recent years we’ve stood up a large and growing industrial complex of derivatives providing products and services that target early-stage founders as “customers”. These all thrive by encouraging more people to start new companies, and to continue to work on them, mostly without too much consideration of the likelihood of success. They increase activity, but often go to great lengths to take attention off the tangible results of that work. They obfuscate the difficult bits and instead focus on what makes being a founder and working on a startup seem glamorous from the outside. By doing that they unintentionally make it less likely that the startups they work with survive and achieve escape velocity – because it’s much harder for those startups to learn the important lessons that only come from feedback loops. In other words, they feel helpful, but they’re making things worse. This is not widely acknowledged or even understood by people who promote derivatives to prospective founders. Or to the bureaucrats and politicians who fund them.

This might sound like a rant, but there is academic research that supports the conclusion. Rasmus Koss Hartmann (Copenhagen Business School), André Spicer (City University, London) and Anders Krabbe (Stanford) investigated this effect in depth and published an amazing paper in 2019: Towards an Untrepreneurial Economy? The Entrepreneurship Industry and the Rise of the Veblenian Entrepreneur.7

This should be compulsory reading for anybody working in the ecosystem. They describe the founders that operate within this type of ecosystem as “Veblenian Entrepreneurs”, after Thorstein Veblen, the economist who coined the expression “conspicuous consumption”. And they make it pretty obvious how they feel about this:

[Veblenian Entrepreneurship] masquerades as being innovation-driven and growth-oriented but is substantively oriented towards supporting the entrepreneur’s conspicuous identity work.

And:

It is a form of entrepreneurship that seeks to appear outwardly as innovation-driven and growth-oriented in order for the founder to gain the social recognition afforded to this category of activity. However, Veblenian Entrepreneurship is substantively different in its triggers and the motivations underlying entrepreneurial activities, and in how the entrepreneur makes use of entrepreneurial resources. Veblenian Entrepreneurship is not triggered by entrepreneurial opportunities. Veblenian Entrepreneurship is triggered by the desire to be an entrepreneur, to build the identity of being an entrepreneur and to ostentatiously project that identity to an audience witnessing and appraising the entrepreneur.

Yikes!

First, do no harm

Let’s consider three specific ways that startup theatre actively damages the ecosystem…

- It amplifies the wrong patterns.

- It consumes all the oxygen in the room.

- It’s a poor use of public funding.

All around the country there are now buildings full of people copying a reality-television-inspired playbook for startups that doesn’t correlate at all with the things that actually successful startups have done. And these patterns are leaking out into other sectors too.8

We dangerously promote the idea that failure is to be encouraged. This creates a perverse feedback loop. The negatives associated with a failed venture get downplayed – because everybody involved has tied their identity to being a successful founder, when something doesn’t work out they talk about the soft positives (such as networking connections made) rather than the hard negatives (such as financial impact, and opportunity costs) and so are less likely to absorb the useful lessons.

We continue to hand the microphone to people running derivatives and the founders they want to promote. Often they are just emulating successful founders, without having done the hard work that creates the success they mimic. Those founders who get media coverage and the associated recognition fundamentally shape what we all consider a founder to be. Only telling stories that make startups seem like a fun game of chance distorts expectations and reduces the likelihood more people will consider it a serious career path. The irony here is that successful founders are often much harder to identify from a distance, partly because they are not so stressed about having to appear successful on the outside.

Meanwhile, significant local and central government funding continues to flow to all these activities, hoping to encourage more successful startups. Most of these have long been proven to be failed experiments, if we are honest about where our successes have come from. But rather than think harder about this we keep doing the same things hoping for a change in fortunes.

Just suck

You may reasonably ask: if it is so dumb, why is startup theatre increasingly common and popular? That’s easily explained too: starting a company is hard. And more than likely to end badly. As a result, we’re all attracted to a reality television approach because we think it might be an easier route, or increase the likelihood of a successful outcome. But it’s a sugar rush. We don’t qualify our startup by winning a business plan competition, or convincing a sucker to invest, or being accepted into an accelerator or incubator programme. We qualify by building something customers want, and we win by selling it repeatedly to them at a price that is greater than our costs. The short cut we hope to find in all this theatre is a mirage. We should realise that anybody promising a short cut is probably trying to sell something.

What’s the alternative?

Many years ago, when our kids were little, we took a family holiday to Noosa in Queensland, Australia. One day, walking in the National Park, we stopped to watch the surfers in the break below us. The waves were big and seemed to me to be crashing close to the rocks, but they made it look effortless and fun. I suggested to Emily that we learn to surf. She corrected me: “You’d love to be able to surf here, but you don’t have the patience to learn to surf here.”

That’s the answer. We have to be prepared to suck. We have to choose Richie McCaw-style Deep Fun.

Unsubscribe

How do we manage these things that are tempting in the moment but bad for us over the long term? The amount of noise created by startup theatre can easily drown out the signal, but it’s all optional. We can each choose to moderate our level of involvement or abstain altogether. Nobody should feel obliged or compelled to participate.9

If you’re starting something new, accept that for quite a while it’s not going to be great. But maybe you’ll look back later and realise how much you enjoyed sucking, or more accurately how much you enjoyed sucking slightly less each day. Don’t be tempted too soon by the glare of the spotlight. The goal isn’t to be famous at any cost, and it’s better to make mistakes in relative obscurity. Contrary to what you’re told by people who love startup theatre, successfully growing a company is much less about discovering the magic spark and much more about the repeated hard grind. Take a few small steps forward each day and soon you’ll look back and be staggered by how far you’ve come. The best and arguably only way to learn about startups is to be part of a startup. Ignore The Apprentice and do an actual apprenticeship. It’s very easy: there are more and more high-growth startups now that are all desperate for team members.

Of course, there’s still no guarantee. Despite Dave Grohl’s experience, not every group of friends playing grunge in their garage in Seattle in the 90s became Nirvana.

-

Are you not entertained? Is this not why you are here?

↩︎ -

McCaw’s Last Stand by Gregor Paul, NZ Herald, 24 June 2015.

Interestingly, in the documentary Chasing Great about his final season in 2015, McCaw shows a page from his pre-match notebook where one of the things he has written is “Enjoy”, so maybe he had mixed feelings about this. ↩︎

-

This builds on Kelly Cordes’ ideas in “The Fun Scale”, Uncommon Path, 24 October 2014. ↩︎

-

The canonical example of Not Fun is the expedition to Antarctica in 1914 led by Ernest Shackleton. They intended to cross the continent on foot. Their ship, the Endurance, became trapped in ice. Everybody survived, which was remarkable. But nobody had any fun. ↩︎

-

Paul Nightingale and Alex Coad memorably called these sub-scale ventures “muppets” in their 2013 paper “Muppets and gazelles: political and methodological biases in entrepreneurship research”. ↩︎

-

Rock ’n’ Roll Jedi by Steve Marsh, Delta Sky Magazine, March 2013. ↩︎

-

Towards an Untrepreneurial Economy? The Entrepreneurship Industry and the Rise of the Veblenian Entrepreneur, by Rasmus Koss Hartmann, André Spicer and Anders Krabbe, November 2019. ↩︎

-

To pick one example, the Ministry of Culture & Heritage announced a $60m Innovation Fund, to be delivered via multiple regional events. As explained in the Q&A on their website:

Why is the Innovation Fund being delivered through events?

Te Urungi is an adaption of event-based models that have been used successfully to generate innovation in different sectors including government, technology and science.They are copying a pattern that they think has generated “innovation” in different sectors, when there is very little evidence that it has. ↩︎

-

If our problem is that once we start we just can’t stop then we need to abstain. If our problem is that we overindulge and have so much of a good thing it becomes a bad thing then we need to moderate. ↩︎

Related Essays

Derivatives

How do all of the programs designed to support startups actually help?

Flailing

Here is some unusual advice for people working on a startup, or thinking about it: swim.

Rich vs Famous

If you had to choose, would you rather be rich or famous?

Pining for the Fjords

Be honest: Can we get to the next milestone with the resources we have?

Leap of Faith

Don’t confuse risk with uncertainty - be clear about what we know is true and what we hope might be true.

The Triple Threat

There are only three ways to be wrong about our impact: neglect, error and malice.

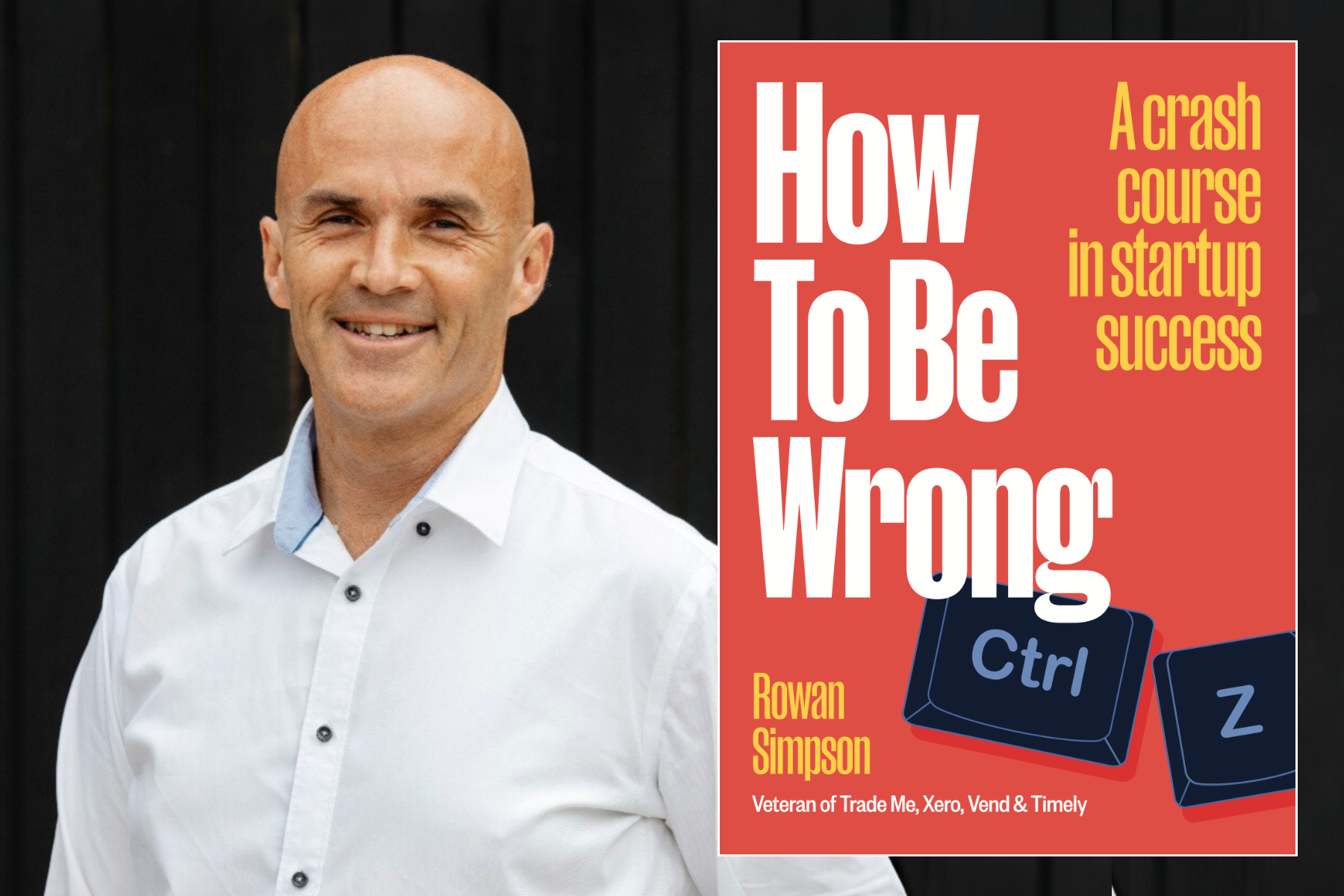

Buy the book