Many startup founders like to quote Yoda in a scene from Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back. “There is no ‘try’,” they say, incorrectly believing their only options are “do or do not”.

I think this is terrible advice. From everything I’ve seen: there is only try. Until we try we just don’t know. Once we try then we find out. Experiments are how we solve problems.

The practical reality of constantly experimenting is much less magic spark and much more repeatable hard grind.1 And there is an obvious reason for this. Curiously it’s also Yoda who puts this into words (he contains multitudes and is full of contradictions). Later in that same scene he says: “Always in motion is the future.”

That’s why startups are hard. We’re attempting something that may or may not be possible. And we’re doing it in an environment that is constantly changing. We’re surrounded by uncertainty. But we can always try.

Three perspectives

How do we know we’re making progress, and not just spinning our wheels? The key is: feedback loops, compounded over time. Any team that is constantly improving is a daunting opponent. When we apply lessons we’ve learned in the past to things we’re working on now it creates momentum. When we measure the things that matter most we have a much better foundation to base future decisions on. When we leverage the experience of everybody we work with and everybody who is willing to help, the result can be transformative. The key that unlocks all these things is when outputs become inputs – when the decisions we make are informed by feedback. While this theory might be obvious, it’s much harder to achieve in practice.

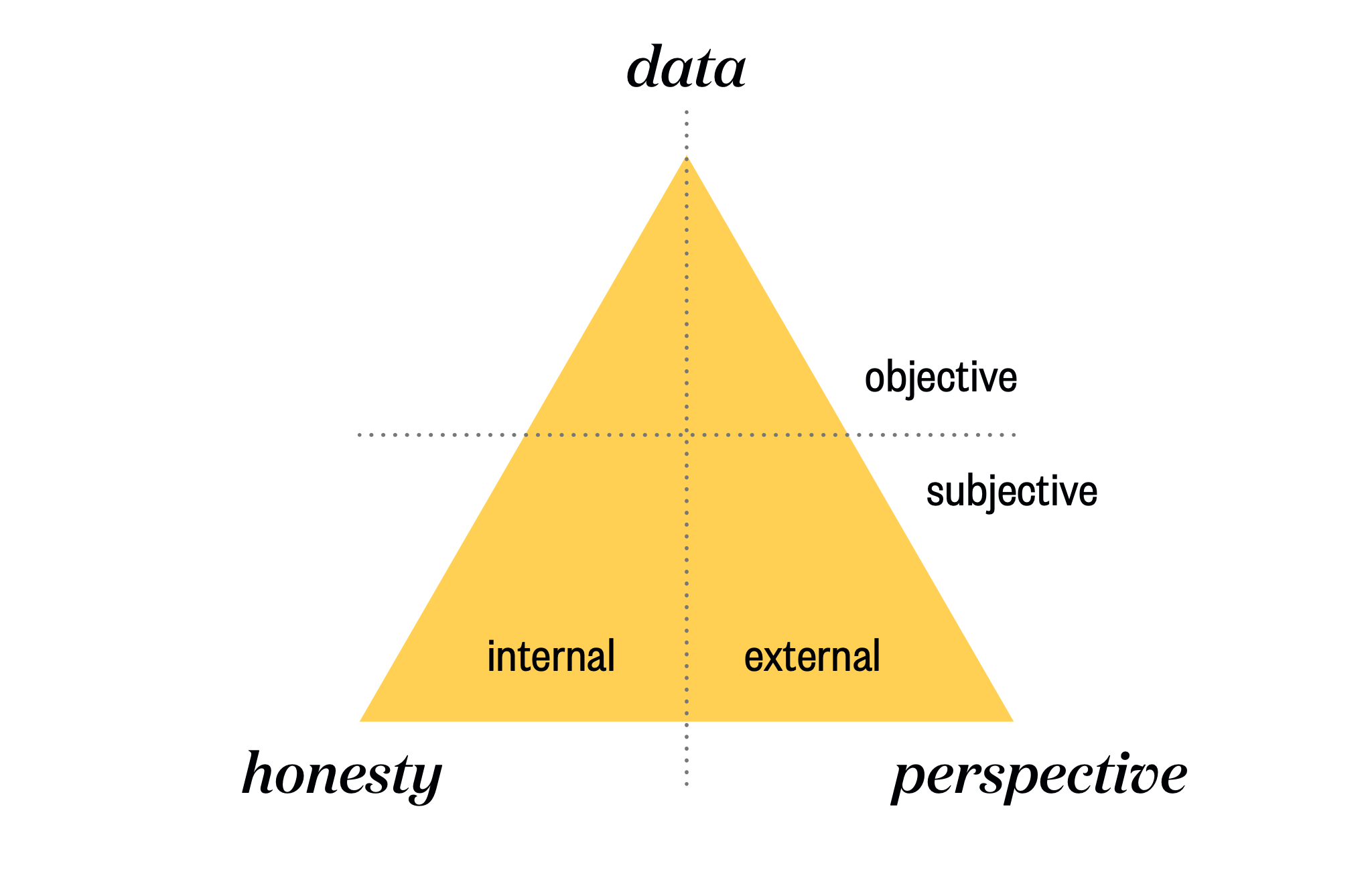

There are actually three very different perspectives we need to consider when thinking about feedback: 2

First, we need to start with the objective results we can measure. Ideally these will be clarity metrics, which are actionable because they highlight trends in our performance and help us to decide what to do differently in the future, rather than vanity metrics, which make us feel good but don’t really teach us anything useful.

Secondly, to complement data, we should also consider subjective perspectives – both internal and external. We need people who can give us an external view and identify our blind spots. Ideally people with enough distance from the risks and rewards of what we’re working on, so they are not distracted by those things. And, at the same time, close enough, experienced enough and trusted enough that we pay attention whenever they say, “I noticed…”

But, third and perhaps most importantly, we need to be completely honest with ourselves about our contribution. It’s too easy to hold on to the things that we hope and dream might be true, and in the process deceive ourselves about what’s working. This is especially true when we are just getting started on something new, when there is necessarily a big gap between what we want to project to the world and our internal reality. Ignoring the aspects that only we can see makes it much harder to close that gap over time. This is how I like to visualise it:

Considering our performance from all three perspectives means we’re more likely to see the full picture of what’s happening and why. Then we can ask better questions about what we should do differently in the future.

Assessing our own performance is harder than it might seem in theory. Here are some practical techniques I’ve used in the teams I’ve worked with.

We think about what we are going to do, and only rarely of that, and fail to think about what we have done, yet any plans for the future are dependant on the past.

Don’t look back in anger

One of the most important skills for any team to learn is how to review. When we develop a habit of consistently and regularly looking back at the work we’ve done, asking what results we got and what we want to do differently next time, then we have the important elements we need to improve.

Most teams are familiar with the idea of a debrief when something has gone badly wrong. But it’s much more useful to make this something we do all the time, and especially when something has gone well.3 For example, an executive team or board might have a brief review at the end of every meeting. Doing that consistently makes it part of a normal process, rather than something to be anxious about on the rare occasions when it happens, and also less likely to be skipped. Little misalignments can be identified immediately and corrected before they have a chance to fester and become more serious. Sometimes results go our way, which is great. But unless we take the time to know why, the next time, when they don’t, we won’t know then either. We will be left hoping for the best.

So how do we review? We can be systematic. (I’m using “review” here rather than “debrief” intentionally to acknowledge that there is a wide spectrum that can fall under that label, from a quick huddle after a meeting to reflect on what just happened all the way through to a more formal and independent inquiry that investigates the outcomes and root causes.)

I like to start with some simple, open-ended questions laid out by Kerry Spackman in The Winner’s Bible:

- What went well?

- What didn’t go well? (What happened, rather than who was “at fault”.)

Then, go deeper:

- What was surprising or unexpected?

- Why did that happen?

- What did others do or not do that we didn’t anticipate? (Both good and bad.)

- How did we respond? (Again, both good and bad.)

Finally, the most important question:

- What did we learn?

I just have one simple request: please call them lessons rather than learnings.4 Even better, call them experiences.

One step ahead

We don’t need to wait until after the fact to ask these questions. It’s more impactful to consider them in advance and try to anticipate.

For any startup, it can be difficult to keep in mind the small number of things that are critical to performance, especially when we’re talking about things we do all the time: team meetings, sales calls, software upgrades and so on. This is accentuated when it’s a diverse team which may contain conflicting objectives. If we take time in advance to say the things we are worried about out loud, in front of our teammates, including all the things we might think but are too afraid or polite to articulate, then that creates a shared understanding. And, sometimes, it brings real clarity about the things that will make a difference to outcomes while there is still time to influence them.

So how do we anticipate? It requires some imagination.

First, imagine a situation in which we didn’t achieve our goal:

- What are the things that we would say contributed to our failure?

- What explanations or excuses would we give?

We could call this a “pre-mortem”.

Then, and even more importantly, imagine instead that we have achieved our goal:

- What are the things that we would say contributed to our success?

- What are the things that we controlled and would get credit for, as opposed to things that just happened to us?

These are especially useful questions to ask in advance, because after the fact we are looking back in the knowledge that we were successful (or not), so decisions that were not obvious are much more visible.5

Then, based on our answers to those two sets of questions, what are the things we can do right now to minimise or accentuate these things, to increase the chance of success and decrease the chance of failure? We don’t need to wait for things to happen to us. We can review and anticipate and create our own insights and competitive advantage.

Give and take

Providing feedback to others is a vital skill, and a delicate art. Whenever we share our perspective, we tread the fine line between helping shine a light on blind spots and highlighting uncomfortable weaknesses. We need to be careful not to be a “seagull”, swooping in, shitting all over the place then quickly flying away again.

Likewise, receiving feedback is a skill that can be developed. Most importantly, by learning to listen without immediately needing to respond, either to deflect or fight back.

For example, here is a common pattern:

Person A: “We need to do X.”

Person B: “Umm, I can see some problems with X.”

Person A: “Well, what are you going to do about that?”

If we insist that every observation from somebody reviewing our work comes with a proposed solution, we’ll get far less feedback. If responsibility for fixing broken things always falls to the person who reports the issue, eventually nobody will report issues. It’s unlikely that the person giving this kind of feedback is the best person to solve the problem they are describing anyway. Identifying problems and solving problems are different skills. Remember evidence is the key to identifying problems, experiments are the key to solving problems. Ultimately we all need to solve the problems with our own work, by experimenting with possible solutions and seeing what results we get. Even just to acknowledge there are problems when they are pointed out is better than immediately deflecting that work back to the person trying to help.

Another variant:

Person A: “I’m doing this new thing Y.”

Person B: “Ooh, interesting. I’ve thought a lot about Y. Here are some of the challenges I see with your solution…”

Person A: “Why are you always so negative? I only ever hear you criticise. Can’t you just say something constructive for once?”

If we take every piece of feedback as a chance to start an argument we’ll get less feedback. Perhaps the person giving feedback intends to offend, but probably not. It’s nearly always better to assume the best in these situations. We need to reframe from feeling hurt by “negative feedback” to consciously seeking out “useful friction”. It’s difficult to find the balance between being delicate with new ideas, so they have an opportunity to grow and develop, and being brutal with new ideas, so they are tested and challenged and improved.

What do you need, right now?

We should decide what makes us more uncomfortable: the possibility that we might be wrong, or the experience of having somebody show us we’re wrong? For many it seems to be the latter – they prefer good news that is probably false (like forecasts) to bad news that is likely true (like sales numbers). Often the reason receiving feedback makes us defensive is simply that it’s poorly timed. Being more explicit about the type of feedback that is useful at each stage, and asking for it, can make a big difference.

Early on, when all we have is a rough idea, feedback on the concept is valuable but feedback on the polish is premature. Later, when the idea has been developed further, but still has some rough edges, feedback on the detail is valuable but feedback on the core concept is too late, and so more likely to be annoying than productive.

It helps to develop a shared language for this within our teams, so we can be more explicit about the type of feedback we want when we share our work. I like to say “30% feedback, please” when I’m sharing something that I’ve just started working on, indicating it’s less than a third complete. And, later, “70% feedback” when I’m ready for help getting it to the finish line.6

The more we see the resulting work improved by feedback we get from others, the more willing we become to share in the future. That creates an environment where everybody in the team is willing to share work-in-progress while it can still be improved. Then we give ourselves the chance of creating something really great.

-

Yield = Accuracy + Frequency, by Vend Product, Design + Engineering Teams, UXDX. ↩︎

-

I was introduced to David Slyfield by Rob Waddell in 2016. He said: “Dave is like you but for Olympians. You are like him but for startups.” I was flattered and intrigued.

His name is not well known, and that’s the way he likes it. But you may recognise the people he’s worked with over the years: Sarah Ulmer, Hamish Carter, Barbara Kendall, Cameron Brown, Sarah Walker, Blair Tuke & Peter Burling, and many others.

I quickly learned his super power is asking probing questions. He has an amazing library of mental models and techniques that he’s collected over the years and an ability to quickly narrow in on the one that is most applicable. See also: The far side of complex.

He is not only a great teacher but also a quintessential quiet one. ↩︎

-

After-event reviews: drawing lessons from successful and failed experience, by Shmuel Ellis & Inbar Davidi, Journal of Applied Psychology, September 2005. ↩︎

-

The plural of lesson is “lessons”. And a “takeaway” is a quick and easy meal. ↩︎

-

This is known as the Historian’s Fallacy. ↩︎

-

The third variant is “100% feedback, please”. When we eventually reach a point where feedback is no longer useful and we want praise rather than feedback, we should just say that. Anybody on the team who (like me) struggles to see when something is good enough will appreciate that. ↩︎

Related Essays

M3: The Metrics Maturity Model

Use these simple steps to improve how we measure and report our progress.

Leap of Faith

Don’t confuse risk with uncertainty - be clear about what we know is true and what we hope might be true.

The Triple Threat

There are only three ways to be wrong about our impact: neglect, error and malice.

Being Spartan with Ideas

Do you leave your ideas to fend for themselves in the wild or keep them in a safe place?

How to Pitch

We realised that the most effective investment pitches all start with the same two words…

Monochrome

What can rugby teams and rowing squads teach us about building and managing diverse teams?

Buy the book